Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

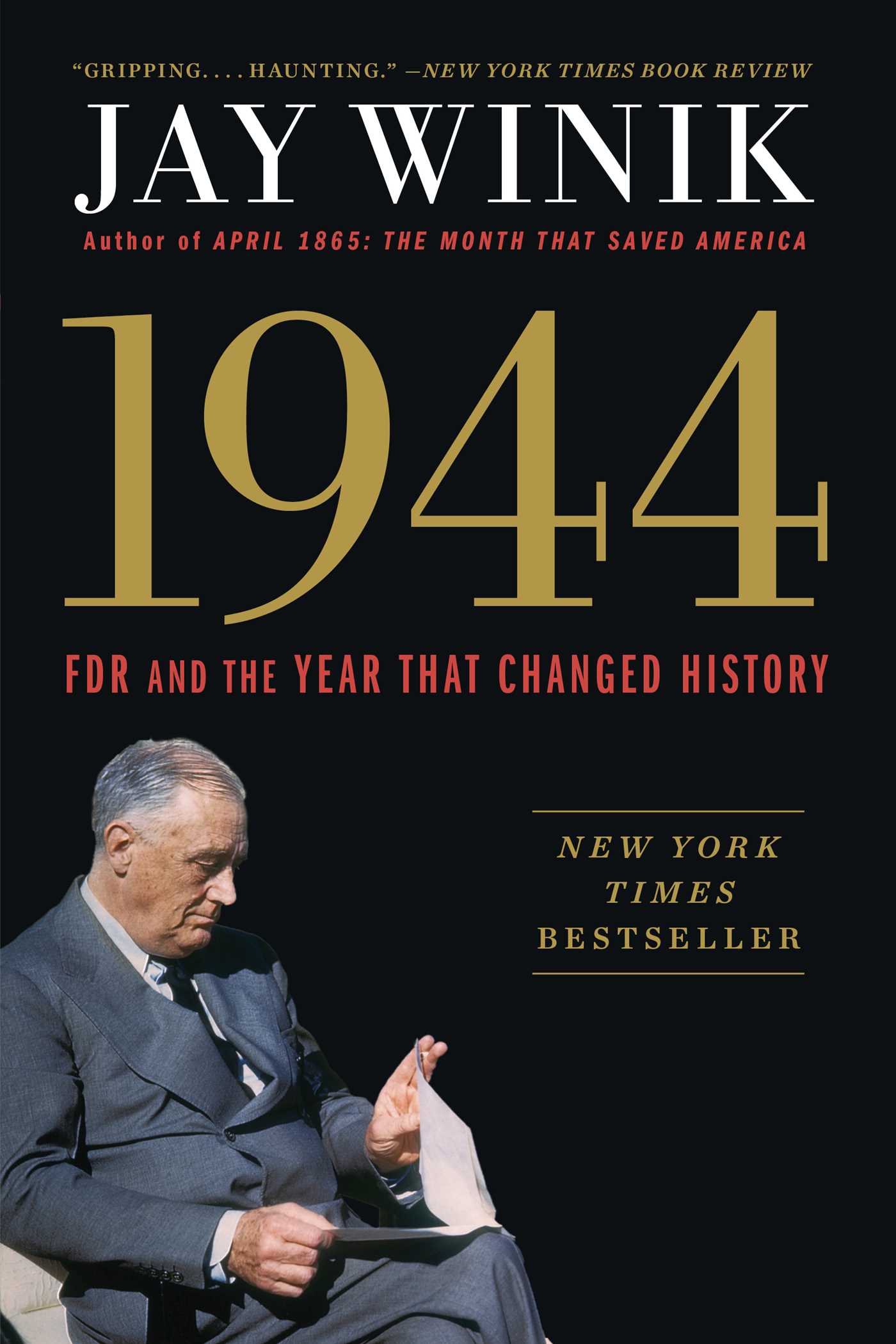

1944 witnessed a series of titanic events: FDR at the pinnacle of his wartime leadership as well as his re-election, the unprecedented D-Day invasion, the liberation of Paris, and the tumultuous conferences that finally shaped the coming peace. But millions of lives were at stake as President Roosevelt learned about Hitler’s Final Solution. Just as the Allies were landing in Normandy, the Nazis were accelerating the killing of millions of European Jews. Winik shows how escalating pressures fell on an infirm Roosevelt, who faced a momentous decision. Was winning the war the best way to rescue the Jews? Or would it get in the way of defeating Hitler? In a year when even the most audacious undertakings were within the world’s reach, one challenge saving Europe’s Jews, seemed to remain beyond Roosevelt’s grasp.

This dramatic account highlights what too often has been glossed over, that as nobly as the Greatest Generation fought under FDR’s command, America could well have done more to thwart Nazi aggression. Destined to take its place as one of the great works of World War II, 1944 is the first book to retell these events with moral clarity and a moving appreciation of the extraordinary actions of many extraordinary leaders.

Excerpt

FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT HAD NEVER wanted to travel to Tehran. Throughout the fall of 1943, the president used his vaunted charm and charisma to push for the three Allied leaders—himself, Winston Churchill, and Joseph Stalin—to meet almost anywhere else. The conference, their first ever, had been a year in the making, and now, before it even commenced, it seemed on the brink of failure over the thorny question of where it would take place.

Dispatched on a visit to Moscow, Secretary of State Cordell Hull had proposed the Iraqi port city of Basra, to which Roosevelt could easily travel by ship. Roosevelt himself suggested Cairo, Baghdad, or Asmara, Italy’s former Eritrean capital on Africa’s east coast; all these were locations, the president pointed out, where he could easily remain in constant contact with Washington, D.C. as was necessary for his wartime stewardship. But the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin, was unmoved. He countered that as commander of the Soviet armed forces he could not be out of contact with his deputies in Moscow. He maintained that Tehran, at the foot of the Elburz Mountains, had telegraph and telephone links with Moscow. “My colleagues insist on Teheran,” he bluntly cabled to Roosevelt in reply, adding that he would however accept a late-November date for the meeting and that he also agreed with the American and British decision to exclude all members of the press.

Roosevelt, still hoping to sway the man he referred to as “Uncle Joe,” cabled again about Basra, saying, “I am begging you to remember that I also have a great obligation to the American government and to maintain the full American war effort.” The answer from Moscow was brief and direct: no. Stalin was adamant, and he now hinted that he might back out of the entire arrangement for a tripartite conference. Not until Roosevelt was preparing to set sail across the Atlantic en route to the Mediterranean did Stalin, having gotten his way on Tehran, finally acquiesce. Roosevelt promptly cabled to Winston Churchill, “I have just heard that Uncle J will come to Teheran. . . . I was in some doubt as to whether he would go through with his former offer . . . but I think that now there is no question that you and I can meet him.”

So it was that at the Cairo West Airport a little past 6:30 a.m. on Saturday, November 27, Roosevelt boarded the Sacred Cow, a gleaming silver Douglas C54 Skymaster that could carry forty-nine passengers and a three-man crew, for the final leg of his momentous journey; in total, he would travel 17,442 miles, crossing and recrossing nearly eight time zones. For his part, Joseph Stalin simply had to travel due south from Moscow; his round-trip would be only 3,000 miles. But all this seemed forgotten as, for the first time in over four years of war, the leaders of the three great powers were at last to meet, face-to-face, to establish policies designed to bring the carnage to a close. This would be the most important conference of the conflict. As Churchill later wrote, “The difficulties of the American Constitution, Roosevelt’s health, and Stalin’s obduracy . . . were all swept away by the inexorable need of a triple meeting and the failure of every other alternative but a flight to Tehran. So we sailed off into the air from Cairo at the crack of dawn.”

It is difficult, in retrospect, to appreciate the magnitude of this trip, or even how bold it was. The wheelchair-bound president of the United States was flying across the Middle East in wartime, unaccompanied by military aircraft and not even in his own plane. The first official presidential airplane, nicknamed Guess Where II, was nothing more than a reconfigured B24 bomber, designated a C87A Liberator; and in any case Roosevelt never used it. After another C87A crashed and the design was found to have an alarming risk of fire—which Roosevelt dreaded—Guess Where II was quietly pulled from the presidential service. Eleanor Roosevelt took the plane on a goodwill tour of Latin America, and the senior White House staff flew on it, but not the president.

Furthermore, Franklin Roosevelt hated to fly.

The paraplegic president preferred almost any mode of travel on solid ground, but even here, he had qualms: for one thing, he could not bear to ride in a train that traveled faster than thirty miles an hour. His presidential train made him feel especially secure: it had a special suspension to support his lower body, its walls were armored, and the glass was bulletproof. An accomplished sailor, he also felt comfortable on the water, where he could master the pitch and swell of the waves. But flying was an entirely different matter, and one not without considerable personal risk. Even simple turbulence was problematic because the president “could never brace himself against the bumps and jolts with his legs as we could,” recalled Mike Reilly, head of Roosevelt’s Secret Service detail. And Roosevelt knew better than anyone else how he was limited by his useless legs—he would have no chance of crawling away from even a minor plane wreck.

Before the Cairo-to-Tehran flight, Roosevelt had made only two other airplane journeys. One was a 1932 flight to Chicago to accept the Democratic nomination for the presidency, during which all the passengers except Roosevelt and his grown son, Elliott, succumbed to airsickness. Before takeoff, mechanics had helpfully removed one of the seats to provide more room, but none of the passengers had seatbelts, so they had to cling to the upholstered arms of their aluminum chairs or risk being tossed about when the plane hit turbulence. The interior noise from the engines was deafening, and the plane’s top speed was just over a hundred miles per hour. Two military aircraft providing an escort as well as a chartered plane carrying reporters turned back in the face of thunderstorms and heavy headwinds, while the plane carrying Roosevelt soldiered on. Then, in January 1943, Roosevelt again took to the skies to meet with Churchill in Casablanca. His party of eight departed from Miami in a forty-passenger plane, the Dixie Clipper, which leapfrogged south across the Caribbean to Brazil and then spent nineteen hours making the 2,500-mile Atlantic crossing from South America to West Africa. The clipper planes, although they had spacious cabins and sleeping quarters including a double bed for Roosevelt, were unpressurized, and at the higher altitudes the president would turn pale, sometimes needing to inhale supplemental oxygen. Indeed, the flight to Casablanca, the first airplane trip by an incumbent president, did not make him any more of a convert to flying. As Roosevelt wrote to his wife, Eleanor, who was by contrast an enthusiastic flier, “You can have your clouds. They bore me.”

But here he was, only ten months later, aloft again, this time in the Sacred Cow.

The 1,300-mile journey that morning took Roosevelt east, roaring through the brilliant sunshine across the Suez Canal and the vast expanses of the Sinai desert; the pilot then dipped down to circle low over the holy cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem, glistening in the morning’s rays. Next, the plane soared over chains of ancient wadis, followed by the hallowed ground of Masada, the rugged fortress in the Judaean hills where a small band of Jews chose death rather than slavery, outlasting an entire Roman legion for nearly three months in the spring of A.D. 73. When the plane reached Baghdad, it turned northeast, where the pilot raced along the Abadan–Tehran highway, guiding the plane through a tricky series of jagged mountain passes. There was no alternative: the plane needed to stay below six thousand feet to keep the oxygen level stable for the president. As Roosevelt peered out the plane’s window, the land below was a chain of mountains rising from a rocky desert, resembling a brown, faded moonscape. It was isolated and empty, except for the exhilarating sight of trains and truck convoys loaded with American-made war matériel, all headed north to the eastern front.

SIX AND A HALF hours later, the president’s plane landed at 3 p.m. at a Red Army airfield in Tehran. Stalin was already waiting. He had arrived in the city twenty-four hours before the British and the Americans and was ensconced at the Russian legation, where he had personally overseen the bugging of a suite of private rooms where the American president would eventually stay.

“Shabby” was how Elliott Roosevelt, the president’s son, described Tehran in late November 1943. The Iranian capital was almost literally a cesspool. Except at the American, Soviet, and British legations, running water was practically nonexistent. Residents and visitors alike scooped their drinking water from a stream that ran along the street gutter, the same stream that also served as the city’s sewage disposal system. Downtown, much of the public drinking water was contaminated with refuse and offal; each sip risked typhus or dysentery, and outbreaks of typhoid fever were common. The city was unappealing in other ways as well. It was occupied by Allied forces, and even the most basic goods were in short supply; a year’s salary might be spent on a sack of flour.

Nor was the city a glamorous place, able to recall a storied past. Among world capitals, Tehran was—surprisingly—almost as much of a newcomer as the young Washington, D.C., had been at its inception, when it was little more than a charming semirural landscape derided as a city of “magnificent distances.” By contrast, in 1800, Tehran’s total population of about twenty thousand had lived inside twenty-foot-high mud walls, which were bounded by a forty-foot-wide moat as deep as thirty feet.

The entire city itself was accessible by a total of four gates. By 1943, the gates had been pulled down, and a newer city had sprung up beyond the original walls. Gone were many of the quaint old houses that had faced an intricate series of elaborate courtyards and fabled Persian gardens; gone were the donkey carts laden with dates and figs and honey and henna en route to the bustling markets. Instead, newer homes looked outward toward wide main streets designed to accommodate automobiles, trucks, and the occasional horse or wheelbarrow. And beyond its modern boulevards, the city emptied out into a vast, barren space with little more than grazing land and oil fields.

The drive from the airfield to downtown Tehran was far from tranquil. The route took the leaders and the accompanying aides through long stretches of curious onlookers and many miles of unprotected road. Before arriving forty-five minutes after the Americans, Winston Churchill, like Roosevelt before him, had endured a potentially deadly journey not unlike that of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914 through the streets of Sarajevo. Churchill’s daughter, Sarah, who was with him, thought the drive “spine-chilling.” The roads were rough, the crowds were ubiquitous, and there was only the barest security. Churchill himself drily remarked, “If it had been planned out beforehand to run the greatest risks . . . the problem could not have been solved more perfectly.” The prime minister and his daughter were traveling in an unsecured car, while their British security detail followed in a closed jeep, too far behind to be of much use should trouble arise.

The route into the city was lined with magnificent white horses of the Persian cavalry—in Tehran itself, crowds four or five people deep thronged in between the gleaming animals. Meanwhile, the Allied security details constantly feared a well-lobbed grenade or a pistol shot, and for good reason: near the end of the drive, the British car came to a halt in traffic and curious Iranians swarmed the vehicle. Undaunted, Churchill kept smiling at the crowd until the traffic parted and he was under way again. Once he reached his embassy, tightly guarded by a regiment of Indian Sikhs, he brushed off any meetings and went directly to bed, with a fifth of scotch whisky and a mound of hot-water bottles.

As Churchill took to his bed, Roosevelt was spending his first and only night at the residence of the American minister on the outskirts of Tehran. The residence was about four miles from the Soviet and British embassies, which were nearly adjoining in the center of the city. The American embassy itself was a mile away, so either Roosevelt or Stalin and Churchill would have to travel through Tehran’s unpredictable streets just to meet. Whether because of paranoia, fear of assassination, or perfidy, Stalin seemed particularly unwilling to make the trip to the American residence. In fact, on the day of Roosevelt’s arrival, he turned down the president’s invitation to dinner, pleading exhaustion.

Instead, as Roosevelt was settling in, the Soviets anxiously reported to the Americans that their intelligence services had discovered an assassination plot against some or all of the leaders at the conference. The Soviet NKVD, forerunner of the KGB (state security committee), claimed that thirty-eight Nazi paratroopers had been dropped inside Russian territory around Tehran; only thirty-two were now accounted for, yet six remained missing, and these had a radio transmitter. Was this a genuine concern, or was it fabricated by the Soviets? That was unclear. In any event, to prevent a problem, Stalin offered Roosevelt a suite of rooms at the heavily guarded Soviet complex for the remainder of the time in Tehran. This was actually Stalin’s second such invitation. The first Roosevelt had politely declined through an envoy. This time the president accepted. The following day he moved his personal staff to the large Soviet complex. Outwardly, Roosevelt displayed little concern; not so his Secret Service. Very much worried about the apparent German threat, the Secret Service agents lined the entire main route with soldiers and then sent out a heavily armed decoy convoy of cars and jeeps. As soon as this cavalcade had departed and was slowly making its way through Tehran’s central streets, Roosevelt was hustled into another car with a single jeep escort and was sent “tearing” through the ancient side streets of Tehran to the Soviet legation. Roosevelt was highly amused by what he called the “cops and robbers stuff,” but his protection agents, who knew better, were terrified.

Once inside the Soviet compound, the American Secret Service agents quickly discovered that they were very much outnumbered. Across Tehran, some three thousand NKVD agents had already been deployed for Stalin’s personal protection. And nowhere was this more apparent than inside the Soviet residence. “Everywhere you went,” agent Mike Reilly noted, “you would see a brute of a man in a lackey’s white coat busily polishing immaculate glass or dusting dustless furniture. As their arms swung to dust or polish, the clear, cold outline of a Luger automatic could be seen on every hip.” Actually, even Scotland Yard had sent far more protection for Churchill than the Americans had sent for Roosevelt.

FINALLY, THE TEHRAN CONFERENCE of the Allied powers could open. In the next few days, the three leaders and their military men would do no less than chart the Allied course for the remainder of the war, as well as begin to define the outlines of the peace. Yet like the Americans’ security arrangements, the summit was to be almost entirely improvised. The Americans had arrived without even a provision for keeping the minutes of the high-level meetings. To address this glaring oversight, four soldiers with stenographic skills were hastily plucked from the nearby American military camp and assigned to take dictation after each session. But there were still no schedules, and there was no one who had been told to organize the meetings or handle the logistics. As a result, the head of the American Joint Chiefs, General George Marshall, actually missed the first meeting; he had misunderstood the start time and had instead gone sightseeing around the city.

The president had also arrived in Tehran without any position papers, the bureaucratic lifeblood of Washington. In short, the conference was vintage FDR. As always, he had no use for rules or regulations when they did not suit him. His plans were simple: improvise, follow his own instincts, and pursue his own agenda. He had come to Tehran in large part to work his legendary, Prospero-like magic on Stalin. His overarching goal was to make a friend and ally of the Soviet leader, to bring him, as he had brought so many others, into the fold.

It was what Roosevelt had been doing for a lifetime.

FEW MEN IN AMERICAN history brought to the presidency such a combination of prodigious political talents and formidable leadership skills as Franklin Roosevelt. By nature he was a dissembler, a schemer, a deceiver. But he also had an unconquerable will and an ingrained sense of immortality. Too easily forgotten is that when Roosevelt was first elected to the White House, there was sober talk of a revolution, and the American political system seemed to be on the verge of dissolution from within, so great were the strains of the Great Depression. But through improvisation and adjustment, buoyed by his legendary oratory and constant experimentation, Roosevelt managed to uplift a dispirited nation.

Now, as the Allies’ fortunes on the far-off battlefields were changing, the world was looking to him to do the same in the war.

How does one even begin to describe him? No one on the global stage was neutral about him, and he was sui generis in every sense of the word. An astonishing blend of political genius and inspired ambition, he was an aristocrat like Thomas Jefferson, a populist like Andrew Jackson, a crafty politician like Abraham Lincoln, and a beloved figure like George Washington. He was as extravagant as he was original, as formidable as he was cosmopolitan, as mercurial as he was flamboyant, and as provocative as he could be puzzling. And he was tall, a fact obscured when polio cut him down: he was six foot two, the nation’s fourth-tallest president, taller than either Ronald Reagan or Barack Obama. Actually, when he had walked, his gait was bowlegged.

Were there any inklings that he would rise to historic greatness? He was born late in the evening on January 30, 1882, “a beautiful little fellow,” to enormous wealth and privilege; and he was an only child. With impressive foresight, one relative described him as “fair, sweet, cunning.” His doting mother, Sara Delano, became the dominant influence in his life; still, Franklin worshipped his father, James, a lawyer, already in his mid-fifties when Franklin arrived. Reared on the family estate in Hyde Park, New York, he was, in effect, the center of the universe. Roosevelt was homeschooled by tutors and governesses, and fussed over by all sorts of domestic help, all under the watchful eye of Sara. From an early age he was drilled in the finer points of penmanship, the dreary particulars of arithmetic, and the searing lessons of history. And with the benefit of a Swiss teacher, he became fluent in German, French, and Latin. He also absorbed a sense of social responsibility—that the more fortunate should help the less fortunate.

His mother read to him every day—including his favorites, Robinson Crusoe and The Swiss Family Robinson—while his father took him riding, sailing, and hunting. It was a pampered, secure existence. When he was a little boy his mother kept him in dresses and long curls; then she dressed him in Scottish regalia. Eventually, at the age of seven, he wore pants—short pants that were part of miniature sailor suits. Evidently, before age nine he had never taken a bath by himself. He had few friends as a boy; most of his time was spent around adults, often illustrious ones. Indeed, he was five when he met President Grover Cleveland. Cleveland wrapped his hand around Franklin’s head and said, “My little man, I am making a strange wish for you. It is that you may never be president of the United States.”

The Roosevelt family traveled extensively, sojourning annually in Europe; wintering in Washington, D.C., where the family rented the opulent townhouse of the Belgian minister on fashionable K Street; and summering at Campobello, a gorgeous sliver of an island off the rugged coast of Maine, where Franklin fell in love with the water and developed a lifelong passion for sailing. He had a twenty-one-foot boat there, New Moon, which his father gave him as a present. It was also there that Roosevelt began to fantasize about a naval career.

He learned to ride at an early age as well. At the age of two he was already cavorting about with a pet donkey and by the age of six with a Welsh pony. However much he was pampered, his parents sought to instill a sense of responsibility in the young Franklin. How? By giving him dogs to watch over: first a Spitz puppy, then a Saint Bernard, then a Newfoundland, and finally a gorgeous red Irish setter. At the same time, he became an avid collector of stuffed birds, which hung on his walls; of naval Americana, which as an ardent sailor he cherished; and, from the age of five, of stamps, another lifelong interest. Eventually, he would fill more than 150 albums and compile a collection totaling more than 1 million stamps.

When Franklin was nine, his father suffered a mild heart attack, and although James survived for a decade more, he became markedly feeble. For Franklin, who adored and idolized his father, this was nothing less than devastating. Five times over the next seven years the family sought out the warm mineral baths at Bad Nauheim in Germany, believed to have curative powers for ailing heart patients. James fervently embraced the restorative powers of the baths. So did Sara. And, predictably, so did the young Franklin, who would later seek the mineral waters at Warm Springs, Georgia. How did Roosevelt cope with his father’s illness? As with everything else, surprisingly serenely. Here, though he was discreet about it, his sheet anchor was in part his Episcopal faith. He believed then, as he quietly would believe for the rest of his life, that if he put his trust in God, all would turn out well.

At the age of fourteen, he entered Groton, then the most prestigious prep school in the nation; tuition was exorbitant, affordable only by the very rich. The purpose of the school was more than to cultivate intellectual development; it was also to foster “manly Christian character,” moral as well as physical, among America’s most privileged boys. “Character, duty, country” was the daily creed; a monastic existence was the daily life. Roosevelt was bright and able to quickly absorb his studies—he would win the Latin prize. He was also a skilled debater. That was as far as it went, though, for he was neither an original thinker nor particularly introspective. But the school’s founder, the Reverend Endicott Peabody, a charismatic minister, would become a profound influence on Roosevelt, more so than anyone else except for, as Franklin would one day put it, “my father and mother.”

For Peabody, who embodied the ethic of muscular Christianity, the clash of sports was as central to the education of Groton boys as the classes themselves. Consequently, having grown up in the comfort and seclusion of Hyde Park, Roosevelt was a misfit; he had never before played a team sport and wasn’t much of an athlete. It showed. Not surprisingly, he was put on a football squad reserved largely for misfits; it was the second-worst team. Baseball was little better; this time he played on the worst squad. However unremarkable he was, though, his passion never waned; by dint of enthusiasm, he even achieved a letter on the baseball team, not for his play, but because of his efforts as the equipment manager.

By the time he prepared to attend Harvard in the autumn of 1900, the ideals of Groton had become second nature to him: work hard and reap the benefits, plunge into competition, and embrace effort as the key to success.

In the autumn of 1900, Roosevelt enrolled at Harvard, America’s most elite university, then under the leadership of its legendary president Charles W. Eliot. If Groton was where Roosevelt, the pampered only child, developed the social habits of mingling with his peers, Harvard was where he cultivated the ability to guide them. Still, he hardly shed the ways of the idle rich. His was the world of well-connected, sophisticated bons vivants; of mint juleps and polo matches; of riding with the hounds and in crosscountry steeple chases; and of tennis at Bar Harbor and sailing at Newport. As for Roosevelt himself? He lived off campus on Mount Auburn Street in a luxurious three-room corner suite (for the extravagant sum of $400 a year), owned a horse, and was a regular during the busy social season: almost weekly he attended the hunt balls, lavish black-tie dinners, and the endless debutante coming-out parties. When Porcellian, the most illustrious of Harvard’s clubs, turned him down, he was crestfallen. However, he was chosen for Hasty Pudding, where he served as librarian, and for the fraternity Alpha Delta Phi. Moreover, he was elected to the editorial board of the Harvard Crimson, ultimately becoming its president, a great honor. His duties at the Crimson were extensive and often taxing—“the paper takes every moment of time” he wrote to his mother—but he acquitted himself admirably, all the while developing an understanding of the inner workings of the media, which would later serve him well when he entered the political arena. Academically, he coasted through, without challenging himself very much. Thanks to his education at Groton, he was able to skip the mandatory freshman curriculum. As to the electives, he eschewed theoretical courses like philosophy; instead, he gravitated toward history, government, and economics, a subject about which he would later remark, “Everything I was taught was wrong.” And as at Groton, he won no academic honors, although his grades were solid.

During the late autumn of his freshman year, he received word that his father had suffered one more heart attack, then another. The family rushed to New York so that James might be closer to the specialists, but this did little for his worsening condition. With his loved ones collected at his bedside, he died at 2:20 a.m. on December 8, 1900. Though it was a great loss emotionally, the family would never want for anything material. Two years earlier, when her own father died, Sara had inherited an amount equivalent to roughly $37 million today. Upon James’s passing, he left Sara and Franklin an estate that would be worth more than $17 million today.

Grief stricken, the family coped by traveling. Rather than going back to Campobello that summer, Franklin and Sara spent ten weeks abroad in Europe: first on an elegant cruise liner that took them through the majestic fjords of Norway and around the arctic circle, where they met Kaiser Wilhelm II. They then went on to Dresden, where Sara had gone to school as a girl, followed by time on the shores of Lake Geneva where they could breathe the crisp air. Finally, they went on to Paris, where they learned that President William McKinley had been assassinated. Their lives would never again be the same. They were not simply rich, but suddenly political royalty: the inimitable Theodore Roosevelt, their cousin, was now president.

That first winter without James was a difficult transition. Sara found life without him barren. She did her best to keep busy, supervising the estate’s many workmen and overseeing its frequently intricate if not chaotic business affairs. But she soon prepared to focus her unwavering attention upon her son.

As the new year opened, Franklin spent three whirlwind days in Washington, D.C., in honor of his cousin Theodore’s daughter Alice, at the White House; it was her coming-out party. The president also invited Franklin for a private talk over tea, twice. “One of the most interesting and enjoyable three days I have ever had,” he wrote to his mother.

Shortly after Roosevelt returned to Harvard, his mother moved to Boston to join him. Rattling around in the house by herself, she found life at Hyde Park unbearable without her husband; she now wanted to be with Franklin. She moved into an apartment, made new friends, and joined the cloistered, elite world of Boston Brahmins. She also became a constant in Roosevelt’s life, and far from resenting it, he enjoyed having her there. Not infrequently, he asked his mother to approve his dates.

Roosevelt loved the company of women. For a decade and a half he had scarcely any contact with the opposite sex and, in part due to the era of Victorian restraint, he had not much more once he arrived at Groton. Harvard was a different story. He fell in love with the lovely Frances Dana, though he was talked out of marriage by his mother because Frances was a Catholic, and the Roosevelts and Delanos were Protestants. Then there was Alice Sohier, the daughter of a distinguished North Shore family who lived in an elegant town house in Boston. He and Alice discussed marriage. An only child, Roosevelt exuberantly confessed he wanted six children. Alice balked at the prospect, confiding to an intimate, “I did not wish to be a cow.” In the autumn of 1902, she backed out of the relationship and went instead to Europe. That was when he met Eleanor, a tall, “regal,” “coltish looking” blue-eyed young woman, who was his fifth cousin once removed, and the orphaned daughter of his godfather, Elliott Roosevelt. Eleanor and Franklin’s courtship was, in a sense, carefully choreographed.

Creatures of elegant New York society, they attended the premier horse show that autumn at Madison Square Garden, perched in the family box. Later, they lazed together on the manicured grass at Springwood, under the watchful eye of a chaperone. They took a dinner cruise aboard Roosevelt’s motorized sailing yacht, the Half-Moon. And that New Year’s Day they were in Washington as part of the inner circle as Theodore—who was her uncle as well as Franklin’s cousin—stood in the East Room of the White House, warmly greeting long lines of supporters; soon, amid the polished silver and glittering candelabras, they dined with Theodore himself in the state dining room. But Franklin’s mind was far away from politics. “E is an angel,” a smitten Roosevelt wrote in his diary.

Eleanor’s world was even more sheltered than Franklin’s—and more tragedy-laced. When Eleanor was eight, her mother, Anna Rebecca Hall, who was often debilitated by migraines and bouts of dark depression, died of diphtheria. Two years later, her father, Elliott, died. A charming playboy who had dropped out of high school, he suffered from numerous inner demons, and his excesses knew no bounds: he was a dashing philanderer, and when he wasn’t taking morphine or laudanum, he was drinking heavily, up to half a dozen bottles of hard liquor daily. One night he was even too drunk to tell a cabbie where he lived. Another time, he almost jumped from his parlor window. And on August 13, 1894, he lost consciousness, alone; he was dead the next evening.

From then on Eleanor lived with her maternal grandmother at their elegant brownstone on West Thirty-seventh Street or their estate on the Hudson—or she attended boarding school at Wimbledon Park in England. Hers was a solemn existence. Frequently surrounded by cooks, butlers, housemaids, laundresses, coachmen, and tutors, she had few friends and virtually no opportunity to meet other children, except for Theodore Roosevelt’s daughter Alice. Unlike Franklin’s mother, Eleanor’s grandmother was a strict disciplinarian. Eleanor’s life became an exercise in self-improvement: piano, dance class, lawn tennis, shooting, and riding. Like Franklin, she was also tutored in German and French, and she became fluent in French. Just as Roosevelt could chat easily in German, she could conduct extensive conversations in French. In time, she also excelled in Italian.

Still, she lacked self-confidence and considered herself an ugly duckling. But as the months passed, she shrewdly learned to compensate for her self-doubts. When she entered boarding school at the age of fifteen, in England at Allenwood—in many ways as prestigious as Groton—where classes were conducted entirely in French, she became the most popular girl in the school. She was earnest and eager and hardworking. She was also a quick study. The school’s headmistress was an ardent feminist—this was rare for the times—and Eleanor learned to question the orthodoxy of the day and to freely express her thoughts, a scandalous liberty in the rigid, patriarchal age of Victorianism. Slender and sophisticated, already at a young age she was an ardent Progressive, taking an interest in political events. She would later comment that under the tutelage of the headmistress, who had a profound influence on her, she developed a “liberal mind and a strong personality.” And unlike Franklin, whose success at sports was modest at best, she made the first team in field hockey.

In the cool autumn days of 1903, Roosevelt and Eleanor dated, always, of course, with a chaperone. He asked her to come to Cambridge for the big game—Harvard versus Yale. The next day, under a clear sky, the two ambled along the Nashua River. Roosevelt proposed; she accepted. When he told his mother at Thanksgiving, Sara was aghast, believing that he was simply too young. She entreated the young couple to keep the engagement secret for a year. However, she did not object to Eleanor, nor did she try to forbid the marriage. They accepted the arrangement. In the meantime Eleanor wrote letters to Franklin brimming with affection—she called him “boy darling,” or “Franklin dearest.” In turn her nickname was “Little Nell.”

In September 1904, Franklin and his mother moved to 200 Madison Avenue, a massive brick town house near J. P. Morgan’s stately mansion, and Franklin entered Columbia Law School. This was prelude. On October 11, a buoyant Roosevelt gave Eleanor an engagement ring from Tiffany’s. She was just twenty, and their arrangement was now official. When their engagement was announced and they were receiving a flurry of congratulations, Theodore Roosevelt insisted the wedding take place in the White House “under his roof.” They demurred. Instead the lavish wedding took place at Eleanor’s great-aunt’s twin town houses; there were top hats and elegant carriages, and Theodore himself was there to give the bride away. The couple had two honeymoons: the first was a modest week away; the second was a three-month grand tour that took them to London, Scotland, Paris, Milan, Verona, Venice, Saint Moritz, and the Black Forest. Roosevelt bought Eleanor a dozen dresses and a long sable coat, and, for himself, a silver fox coat and an old library: three thousand leather-bound books.

At Columbia Law School, as at Harvard, he was an undistinguished student, receiving B’s, C’s, and a D. Vaguely bored and wealthy, confident and even a bit cocky, he seldom let studies stand in the way of a good time. One Columbia professor remarked that Roosevelt had little aptitude for the law—actually, he had initially failed courses in contracts and civil procedure—and that he “made no effort” to overcome the problem with hard work. Nevertheless, he easily passed the New York bar examination in his third year, upon which he promptly dropped out of school; he never earned his degree. Meanwhile, at Christmastime in 1905, Sara told the newlyweds that she had hired a firm to construct a town house for them (“a Christmastime present from mama”), which would adjoin a second home: hers; the dining rooms and drawing rooms of the two homes opened into each other. Very much her own woman, Eleanor was deeply unhappy with the fact that Sara was making so many major decisions for her family. But Roosevelt was unsympathetic, acting as if there were no problem. As Eleanor herself explained, “I think he always thought that if you ignored a thing long enough it would settle itself.” Three years later, Sara gave Roosevelt and Eleanor a second house, an elegant seaside cottage on the gorgeous shores of Campobello Island. The sprawling home had thirty-four rooms, manicured lawns, shimmering crystal and silver, and seven fireplaces, as well as four full baths—although no electricity.

All told, theirs was a lavish lifestyle. In addition to their three houses, they always had at least five servants, a number of automobiles and carriages, a large yacht, and many smaller boats; Roosevelt continued to love the water. As befitted their station, they belonged to exclusive clubs, dressed stylishly, and donated their money to various charitable causes. As for their five children? They were to be raised by governesses, nurses, and other caregivers. Eleanor, as serious as ever, was the stricter of the two parents. Her grandmother had always been quick to say “no” rather than “yes,” and she was the same. By contrast, Franklin was warm, good-humored, and engaging. As his daughter Anna once said, “Father was fun.”

He was more than fun. Early on, he confessed that he had little taste for the law. Nor was he content with summering at Campobello or sailing at Newport or spending his time at seasonal coming-out parties. With uncommon candor, he explained that he planned to run for office, and audaciously believed he would one day be president. First, he would become a state assemblyman—a low-paying part-time job in Albany—then assistant secretary of the navy, and finally governor of New York. Theodore had made it to the White House following exactly that path; why couldn’t Franklin?

IT HAPPENED ALMOST AS he predicted.

Except at the start. The assemblyman who Roosevelt assumed would step aside to provide him with a seat declined his entreaties. Still, Roosevelt was determined. He first threatened to run as an independent, but was then persuaded to run for the state senate as a Democrat, in the Twenty-sixth District, which had elected only one Democrat to the office in fifty-four years. A committee of three nominated Roosevelt, and the local newspaper, the Republican Poughkeepsie Eagle, sniped that he had been “discovered” by the Democrats more for his deep pockets than for any other redeeming qualities. Roosevelt, in a style he would use again and again, motored around the district in an open touring car, which was painted bright red and owned by a piano tuner. Along with two other local candidates, he crisscrossed the district in this newfangled automobile, purring along at twenty-two miles per hour. He was attentive: as he bumped down the dusty, rutted roads, he made sure that the campaign car was pulled over and the engine shut off whenever a horse-drawn carriage or hay wagon appeared, lest it startle the animals or peeve a voter.

At the outset, he was not a great speaker. His words were too abstract, and he relied too much on flattery of himself and others. But he would speak anywhere—on a front porch, by the side of a road, on the top of a hay bale. Eleanor would describe his style as “slow,” noting that “every now and then there would be a long pause, and I would be worried for fear he would never go on.” With her discerning eye, she thought he looked “tall, high-strung,” and even “nervous.” However, he excelled at working a crowd—his energetic hands seemed permanently outstretched, ready to grip the next open palm. Still, the campaign was often poorly run. Once, while traveling in the eastern edge of the district, he arrived at a small town late in the afternoon, jumped from the car, headed straight to the hotel, and invited everyone in the bar to have a drink—on him. Only after the bartender began pouring did Roosevelt think to ask where he was: Sharon, Connecticut, not only the wrong district but the wrong state. Undaunted, Roosevelt grinned and paid up; and then proceeded to reuse the story and the joke for years. And he had no qualms about trading on his famous name, borrowing his cousin Theodore’s pronunciation of “dee-lighted,” and sometimes announcing to a crowd, “I’m not Teddy,” his way of suggesting that he was the other Roosevelt. On Election Day, despite a last-minute rush by the Republicans, Franklin Roosevelt carried the district by more than 1,100 votes.

The Roosevelts rented a house in Albany, for a princely $4,800 a year. Eleanor, prone to recurring depressions, was at first reluctant about the house, about the job, and about politics in general, but she gritted her teeth and assumed that it was a wife’s duty to be involved in her husband’s interests—although when she had tried her hand at golf, Roosevelt had watched her swing and promptly dissuaded her.

He immersed himself in political life but did not always win over his fellow politicians. He particularly had trouble reaching the Irish-Catholic Democrats. Roosevelt’s father had disdained Irishmen, even as workers in his household, and a leading New York politico, James Farley, claimed that Eleanor had once said to him, “Franklin finds it hard to relax with people who aren’t his social equals.” Eleanor strongly denied it, although in her own early letters she made less than temperate observations about Jews; once, of a party honoring the financier Bernard Baruch (who would later become a close ally), she wrote, “I’d rather be hung than seen there.” And Roosevelt himself was at times clearly uneasy working with different classes outside his own tight circle. As he later acknowledged to his secretary of labor, Frances Perkins, “I was an awfully mean cuss when I first went into politics.” Moreover, if he was a Progressive, he was a cautious one. It took him until 1912 to openly support women’s suffrage, and he would not back a labor reform bill mandating a fifty-four-hour maximum workweek for women and children, even after the devastating fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company, in which more than a hundred female garment workers died.

Then came 1912. Two years after Roosevelt had won his state senate seat, he was running for reelection and Woodrow Wilson was running for president, against Theodore, who was a third-party candidate. Following politics rather than kinship, and, as ever, self-interest most of all, Roosevelt backed Wilson. He had been at the Democratic convention, working the room, ostensibly on behalf of Wilson, but equally on behalf of himself. One of the men he impressed was Josephus Daniels, a member of the Democratic National Committee and also the editor of the Raleigh, North Carolina, News and Observer. But that would be significant later. First, Roosevelt had to win reelection to the state senate, and suddenly that goal was in jeopardy. In September, Roosevelt fell seriously ill with typhoid fever in New York City. He was too sick to campaign, or even to get out of bed. Eventually he recovered, but his political career now seemed imperiled.

It was Eleanor who rescued him by contacting Louis Howe, a dogged Albany newspaperman and political impresario who was enthralled with Roosevelt. She asked whether Howe would consider taking over the campaign. Howe eagerly said yes. In truth, he didn’t look like much, and seemed an odd partner for the patrician Roosevelt. He was squat, asthmatic, and stooped, with a pitted face and a cigarette wobbling between his lips; he was often unbathed as well. Yet he was a political genius who quickly became Roosevelt’s virtual surrogate, taking out full-page newspaper ads and producing a direct-mail campaign of multigraphed letters bearing Roosevelt’s signature. In effect he took over the last six weeks of the campaign. And in a dramatic departure, Howe remade Roosevelt into a full Progressive, supporting labor rights, supporting women’s suffrage, and complaining about Republican political bosses. With Howe at the helm, Roosevelt won reelection by an even wider margin than he had achieved in 1910. When Roosevelt reached the White House, Howe became his secretary—the equivalent of today’s chief of staff—and he did not leave Roosevelt’s side until he died in April 1936.

The state senate was only a stepping-stone. Roosevelt had early on let it be known, to Wilson in particular, that he wanted a job in Washington. He turned down two offers—as an assistant secretary in the Treasury, and as a collector for the Port of New York—holding out for his desire: assistant secretary of the navy. His obstinacy paid off; Wilson gave him the navy job. He would be serving under Josephus Daniels, whom he had befriended during his state senate campaign. Roosevelt now held the same post that had launched his cousin Theodore on the way to the White House.

In the Navy Department, Roosevelt learned about the bureaucracy and the ways of Washington. He brought Louis Howe with him, and this enabled him to also keep tabs on New York. Roosevelt enjoyed the trappings and the ceremony, but as the number two man, he was on the periphery of power, and he knew it. Making the ships run on time was not the role to which Roosevelt aspired. He tried to make a bid himself for the U.S. Senate but failed. His candidacy was rebuffed by his own party and by the president himself—humiliatingly for Roosevelt, Wilson openly backed a rival candidate. Roosevelt was routed in the primary, and never forgave the man who had opposed him, James Gerard, who was the U.S. ambassador to Germany and a former justice of the New York state supreme court. Fortunately World War I intervened, and Roosevelt quickly devised plans for expanding the U.S. Navy (which were ignored) and also improved his ability to testify before Congress (which got him noticed). The efforts worked. By 1916, his stance as a “preparedness Democrat” made him an asset in Wilson’s reelection campaign. Roosevelt was sent to stump in New England and the mid-Atlantic states, and it was here that he first began using his fire hose analogy, the idea of lending one’s own hose to a neighbor whose house is on fire. Over time, he would tweak, amend, and refine this analogy, which became one of the most famous concepts of his political career. He would later use it during World War II to sell a wary American nation on his Lend-Lease policy for Great Britain.

For Roosevelt, when the United States finally entered World War I in April 1917 after the torpedoing of three steamships, the navy was the place to be. At that time it had 60,000 men and 197 ships in active service; at the end of the war it had almost 500,000 men and more than 2,000 ships, a staggering number. Roosevelt threw himself enthusiastically into the expansion and was so successful that he was forced to share some of his newly acquired supplies with the army, and “see young Roosevelt about it” quickly became a catchphrase in Washington. But Roosevelt, as ambitious as he was restless, was unsatisfied. He dreamed of seeing military action, again following in the footsteps of his cousin, but was thwarted at every turn by his superiors, who would not allow him to go overseas, let alone enlist in any branch of the armed forces. Instead, he put his persuasive skills to use, lobbying for the creation of a 240-mile underwater chain of explosives to foil German submarines. Roosevelt’s position in the navy and his work to protect naval shipyards also endeared him to the leaders of Tammany Hall, which dominated New York Democratic politics.

In the capital, the Roosevelts were much in demand. Invitations arrived daily, and Eleanor quickly discovered that the social whirlwind required her to have a social secretary. In 1914, she hired Lucy Mercer to come in three mornings a week. Not long after that, having borne six children, Eleanor informed Franklin that there would be no more babies. To ensure this, Roosevelt was also informed that he was no longer welcome in his wife’s bed.

Roosevelt was a tall, attractive man of thirty-four. When he had first run for the state senate, women had flocked to hear his speeches, even though they could not vote. Now he also had status, a touch of maturity, and roving interests. Lucy, Eleanor’s part-time social secretary, was everything her employer was not, feminine and self-assured with a gentle voice and a “hint of fire in her eyes.” She was also tall, slender, and blue-eyed, with long, light-brown hair. And although her family had long since exhausted its funds, she was nevertheless part of the same hallowed social set as the Roosevelts. Even as she worked in the Roosevelts’ house, Lucy attended the same large dinners and parties as Franklin and Eleanor. Amid the guests, Roosevelt flirted and Lucy flirted back. From there, things quietly escalated. Roosevelt and Lucy went on cruises on the Potomac and long, private drives in Virginia—alone. Once, Alice Roosevelt Longworth, Theodore’s oldest daughter, who had been Eleanor’s maid of honor at her wedding, caught sight of them riding side by side in Roosevelt’s roadster. Alice wrote to Franklin, mentioning that he had never noticed her: “Your hands were on the wheel, but your eyes were on that perfectly lovely lady.”

Eleanor sensed trouble. Not long after a Potomac cruise hosted by Franklin and Eleanor, a suspicious Eleanor terminated Lucy’s employment. She likely did it on the pretext of going away for the summer; she had no proof of any relationship, only her suspicions. Almost immediately, Lucy enlisted in the navy. Not unsurprisingly, her first assignment was secretarial duty at the Navy Department; she had left Roosevelt’s house for his office. Possibly aware of the link between Roosevelt and Lucy, Secretary of the Navy Daniels removed her from her post and then from the navy only a few months later. Yet while distance may have banked their passion, it did not extinguish it. For nearly thirty years, Franklin and Lucy would continue to meet and write to each other. In his last conscious moments in April 1945, it would be Lucy, not Eleanor, who was with him. At the end, it was her voice that he heard and her face that he saw.

THE YEAR 1918 WAS when Franklin Roosevelt was at last determined to go to war. All four of his Republican Roosevelt cousins had signed up for combat. Just as the young Austrian painter Adolf Hitler was itching for action on the front, Roosevelt wanted at least to set foot in Europe, even if he were not in full uniform. Then a congressional delegation announced plans to inspect naval installations during the summer. Secretary Daniels dispatched Roosevelt to ferret out any potential problems. While crossing the Atlantic on a destroyer, he heard bells sound for a U-boat attack, and he raced to the deck. The attack never materialized; the waters remained calm, and the destroyer was unmolested. Yet that outcome was not good enough for Roosevelt. His biographer Jean Edward Smith has observed: “As Roosevelt retold the story through the years, the German submarine came closer and closer until he had almost seen it himself.”

He arrived in England a week after his cousin Quentin Roosevelt was killed in a dogfight over France. After his ship docked, Rolls-Royces whisked Roosevelt to London, where he met the king and the prime minister and came away with a strong dislike of the British Minister of munitions, Winston Churchill, “one of the few men in public life who was rude to me,” he would later tell Joseph Kennedy. From there he went on to Paris, where he was deeply impressed with the presidential wines, “perfect of their kind and perfectly served.” And at each location, letters awaited him, from Eleanor and also from Lucy Mercer. Then he headed for the front. He saw the scarred battlefields of Château-Thierry, Belleau Wood, and Verdun. At Verdun alone there had been some 900,000 casualties; partially and fully exploded shells had obliterated the forts and trenches, and the battlefield was an unrecognizable expanse of brown, churned-up earth. Roosevelt stared at it in silence.

He was still eager, however, to witness action. Once, a shell whistled and landed with a “dull boom” nearby. Roosevelt took off toward the sound, leaving behind a suitcase of important papers on the running board of his car. Yet for all his jaunty enthusiasm, the devastation wrought by combat made a lasting impression on Roosevelt. Later, he would mention the images he had seen in a walk through Belleau Wood: “rain-stained love letters,” or men buried in shallow graves, with nothing more than a weathered rifle butt poking out of the ground to mark their resting place.

After France, he traveled to Italy, where he tried unsuccessfully to negotiate a command structure for the Mediterranean, then back to England. Determined as ever, on his return to Washington he planned to resign his post and head for the front. Again, another foe intervened: Spanish influenza. Roosevelt was struck on board the USS Leviathan, collapsing in his cabin. His flu was compounded by double pneumonia. Clammy and sweating, Roosevelt lay in his bunk barely conscious, hovering near death. He lived. Many others were not so lucky. Death came often during the passage, and both officers and men who passed away on board were buried at sea. Then, when the ship docked, Roosevelt was transported by ambulance to his mother’s New York town house. Four orderlies carried his prostrate body up the stairs. Eleanor had hurriedly arrived to attend to him and dutifully unpacked his bags. In the process, she discovered sheafs of love letters, neatly tied together, all from Lucy Mercer. These letters confirmed her worst fears, and as Eleanor would later put it, “the bottom dropped out of my own particular world.”

According to various family accounts, Eleanor offered to give Franklin a divorce so that he might marry Lucy, but both Louis Howe and Sara Roosevelt were aghast at the idea and convinced him that it would derail his political career. Sara may well have threatened to disown him if he left Eleanor for Lucy. In the end, he stayed, as did Eleanor.

Roosevelt did not recover from either the pneumonia or the discovery of his liaison with Lucy in time to resign his post and enlist in the war. When peace came, he instead pressed his case to return to Europe to preside over the demobilization of the navy, and Daniels finally relented. Franklin and Eleanor were sent together. The trip was a watershed. When they were four days out of New York harbor, word arrived that Teddy Roosevelt was dead. And before the year’s end, President Woodrow Wilson would be paralyzed by a massive stroke. His cherished dream of a League of Nations would collapse, and the 1920 campaign would begin. Roosevelt was there, giving the seconding speech for New York’s Al Smith at the Democratic convention; moreover, he became the party’s nominee for vice president, on the ticket with Governor James Cox of Ohio. Roosevelt again felt no shame in trading on his name: as he had done in running for the New York state senate, he adopted many of Theodore’s characteristic expressions—“b-u-ll-y,” “stren-u-ous.” Yet the campaign soon foundered, and Warren Harding routed Cox and Roosevelt, with more than 60 percent of the popular vote and an impressive 404 votes in the Electoral College. Still, the loss at least proved to be a financial gain for Roosevelt. He became vice president of the Fidelity and Deposit Company of Maryland, for the hefty sum of $25,000 a year, largely for lending his name to the masthead. The Democrats, Roosevelt thought, would be wandering in the wilderness for the near future. With the future ahead of him, he preferred to decamp to his summer home on the island of Campobello, Maine.

IT BEGAN AS A vague malaise and a dull ache in his legs. Then came the exhaustion and shivering. He only picked at his dinner tray and was cold even under a heavy woolen blanket. In the morning, as he was walking to the bathroom, his left leg gave way beneath him. He shaved and made it back to bed. He could not know it then, but this was the last walk he would ever take unassisted.

By now, he had a fever, and the pain in his back and legs had increased. The family attempted massage, but to no avail. Within a week, his frantic doctors were desperate for even a glimpse of movement in one of Roosevelt’s toes. They could not see any. In truth, he could not even use the toilet on his own; a catheter was implanted, which Eleanor got up to drain during the night. By the end of August, there was no improvement. By the end of September, significant muscle atrophy had set in.

He was eventually diagnosed with poliomyelitis, or infantile paralysis, although more recent medical speculation has suggested some form of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Whatever the cause, the outcome was the same. He was a paraplegic.

Nevertheless, on October 15, Franklin Roosevelt reached a milestone. He was able to sit up. He had been transported back to New York City and left the hospital in late October. An intensive exercise regimen was designed to enable him to use crutches. His now-useless legs were laboriously strapped into fourteen-pound steel braces, molded from his ankle to his hips. He could no longer balance on his own or extend one leg at a time. Instead, his crutches became his legs; he stabilized himself using his upper body, and half-dragged, half-swung his legs and his hips along from behind. At Hyde Park, the rope-and-pulley trunk elevator became his conveyance to the upper floors; dutifully, his mother had “inclined planes” installed and removed all the raised thresholds so nothing would impede a wheelchair. Sara Roosevelt hoped her son would retire to Hyde Park, but his political adviser Louis Howe had other ideas.

“I believe,” Howe audaciously said, “someday Franklin will be president.”

THE MAN WHO HAD fallen in a heap when he attempted to navigate on crutches across the slippery marble floor at his Wall Street offices, the man who could not lift even one arm and wave for fear of toppling, the man who had once towered over others but was now almost always the one who did the looking up—miraculously returned to politics in 1924 as a lead speaker for the Democratic presidential convention. What Roosevelt could no longer do with his arms, he did with his head, throwing it back, holding his shoulders high. Whatever parts of himself he could still move, he animated. And he now used his voice brilliantly. No longer halting, it had matured into a resonant tenor and was infused with a passion that he had previously lacked. It thrummed, it vibrated, it sang. And wherever he was, the audience felt it.

In November 1928, Franklin Roosevelt achieved what had once seemed to many to be impossible. He was elected the Democratic governor of New York. He did it by being carried up back stairs to deliver speeches and by riding in the back of a car, from which he could speak without standing up. Indeed, the simple act of standing up and sitting down required more effort for him than most men exert during an entire day. Day after day on the campaign trail, he disguised his disability and seemed to have gained a new equanimity. Frances Perkins, who joined Roosevelt on his run for governor and who would later become his secretary of labor, recalled him telling her once, “If you can’t use your legs and they bring you milk when you wanted orange juice, you learn to say, ‘that’s all right’ and drink it.”

Roosevelt was now truly living what his cousin Teddy had preached: “the strenuous life.” And he lived it not in a charge up San Juan Hill or on a big-game hunt in the western plains, but every waking hour of every day. He lived it from the moment he summoned his strength to hoist his useless legs from his bed into his self-designed wheelchair; he lived it when the sweat ran down his face as he said to himself, “I must get down the driveway” or “I must get to the podium” or “I must get across the room.” He did it minute after minute and week after week, always refusing to give up or give in. As never before, he had become a man of conviction and determination. And when the country was on its knees because of the Great Depression, Governor Roosevelt seemed, however improbably, the man who might best be able to lift it back onto its feet.

ROOSEVELT’S POLITICAL OPERATIVES WERE already preparing their candidate for the presidential election only a few days after he was reelected as New York’s governor. He formally announced his candidacy on January 23, 1932, and proceeded to win all the delegates in Alaska and Washington state in the first week. But he did not succeed in derailing his opposition. In his final speech before the Democratic convention, he promised “bold, persistent experimentation.” “Take a method,” he boomed, “and try it. If it fails admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.” He arrived at the convention with a solid lead, but still about a hundred votes short of the nomination. After a night and a day of fierce lobbying and multiple votes, he finally won on the fourth ballot, claiming more than two thirds of the delegates after California and Texas switched to the Roosevelt column. He then made a dramatic flight to Chicago to accept the nomination, and his words to the assembled crowd thundered over the radio: “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a NEW DEAL for the American people.”

Whatever Roosevelt’s promises, no one could overlook the desperate situation the country found itself in. The Great Depression was horrific. At least 25 percent of the American workforce was unemployed; in some industrial cities, unemployment was as high as 80 or 90 percent. International trade was devastated. In less than four years, the American economy had shrunk by $45 billion, or about 45 percent. Even more staggering than the numbers were the haunting images: the bread lines forming in every city; the evicted families, jobless and destitute and dirty, shuffling from one soup kitchen to the next; and the makeshift tents in the dead of winter buckling from rain and sleet, not to mention the filthy children who huddled by bonfires alongside the railroad tracks. And the great midwestern dust bowl was yet to come. Sometimes, the enormousness of the task and the despair must have seemed overwhelming.

But not to Roosevelt. In his race against Hoover, he gave twenty-seven major addresses, each covering a single topic, and he made his campaign about substance and about organization. Most of all, he believed he would win, and equally remarkably, everyone around him became a believer as well. The embattled incumbent president, Herbert Hoover, accused the Democrats of being the “party of the mob.” Hoover also insisted that despite the Depression, no one was starving: “The hobos,” he exclaimed, “are better fed than they have ever been.” The voters went overwhelmingly against Hoover and for Roosevelt; it was a drubbing—the president carried only six northeastern states. Roosevelt’s Democrats also gained a nearly three-to-one majority in the House and control of the Senate. On election night, Washington seemed to be his.

And there was this: we think of our presidents as robust, vigorous, capable of striding through any part of the country or indeed the globe. But Franklin Roosevelt could not stride. He could not even stand unbraced or unassisted. Never before or since has a disabled person run for the American presidency, let alone won. That he ran and won in a time of national turmoil is a testament not only to the skill of his campaign, but to something fearless and indomitable deep within himself.

“HE HAS BEEN ALL but crowned by the people,” newspaperman William Allen White grandiloquently wrote. Actually, this was an overstatement. True, in the New Deal days he was the man whom millions loved, but he was also the man whom millions loved to hate. In his first hundred days in office, he undid the Temperance movement by repealing Prohibition and rebuffed both organized labor and veterans with his sweeping legislative proposals and executive orders. He remade the banking system and began to remake the government and economy. For Roosevelt, no dream seemed impossible. And to many, as inch-by-inch he restored confidence in the economy and tamed the worst of the Depression, it was nothing less than miraculous.

Yet the heady promise of those early days and months also could not be indefinitely sustained. By the mid-1930s, some of Roosevelt’s presidential magic had begun to wear off. The jaunty, quick-witted president who seemed to relish sparring with his enemies now appeared at times baffled and weary, though he did rebound in 1936—an election year—with a string of legislative achievements reminiscent of the first hundred days of his term. By the end of his second term, however, as he confronted ever-rising difficulties with Congress, continued obstruction from a wary Supreme Court, a persistently sluggish economy, and the ominous sight of Adolf Hitler looming over Europe, he suddenly looked ordinary, much like any other two-term president. Yet once plunged into the throes of World War II, he emerged not only as a great statesman, but as one of history’s originals.

Callous and cunning, he was careful never to get too far ahead of public opinion, even as he pushed, prodded, and manipulated his two very different wartime allies, Churchill and Stalin. Neatly attired and insouciant, he was the very picture of understated upper-class elegance and seemed strangely immune to mercurial passions—Francis Biddle once remarked that Roosevelt “had more serenity than any man I’ve ever met.” And despite his useless legs, he was still a strikingly imposing figure, with his broad torso and wide shoulders. His charm was without peer. When he famously tossed his head back, or flashed a wide grin, his eyes flickered with emotion. When he chuckled with delight, so did those around him. His smile remained infectious, and his company was irresistible: Churchill felt it; so did Stalin; and so did General Dwight Eisenhower, Roosevelt’s chief adviser Harry Hopkins, and Secretary of State Cordell Hull. Roosevelt was a magnet to which thousands were drawn. How else to explain the nearly slavish devotion of those who supported his political endeavors, or the unwritten rule among the press corps never to report on his disability or photograph his wheelchair or his shriveled legs?

In spite of his disability, Roosevelt remained a man of constant action, loving to drive, loving his stamps, loving the interplay of politics. Largely motionless himself, he instead made motion orbit around him, perfecting the tilt of his head and using his cigarette holder like a conductor’s baton. He was given to drumming his fingers when excited. He could infuse equal gusto into discussions of grave international issues such as the “survival of democracy,” as he did into mundane politics such as the fate of a ward heeler in a Pennsylvania precinct. And when angered he could point a threatening finger or display a menacing scowl.

Like all great leaders, he was not above simple demagoguery or ruthless invective when it served his purpose: Roosevelt blithely referred to isolationists as “cheerful idiots”; when he appointed a Republican, he joked to the press corps that he couldn’t find any dollar-a-year men among the Democrats; and when Ambassador William Bullitt fell out of his favor, Roosevelt encouraged him to leave Washington and run for mayor of Philadelphia—and then promptly instructed the Pennsylvania Democratic bosses to “cut his throat.” He once derided Congress as “a madhouse,” and denounced the Senate as “a bunch of incompetent obstructionists.” The commander in chief even thought that his own vice president, Henry Wallace, who served with him for his entire third term, was a crackpot. And he liked to make fun of his secretary of state, cheerfully imitating Hull’s lisp.

But intuitively, Roosevelt understood Adolf Hitler’s bloodthirstiness as much as anyone—ironically, he and Hitler had come to power at the same time, in 1933—and knew that with each new battle and each month of the war, “we are fighting to save a great and precious form of government for ourselves and for the world.”

IN 1933, AFTER HIS first hundred days in office, Roosevelt had brilliantly managed to usher fifteen historic pieces of legislation through Congress. When it was necessary to hold firm, he did that; when it was necessary to compromise, he did that; when it was necessary to make a bargain, he did that as well. “It’s more than a New Deal,” his secretary of the interior, Harold Ickes, boasted: “It’s a new world!” Even when a bleak recession and unemployment lingered and when he failed in his attempt to “pack” a restive Supreme Court, he never lost the adulation of vast segments of the public or the interest of the press.

Yet when it came to the darkening situation in Europe, Roosevelt flinched. Instead of showing his customary confidence, he played it coyly. Despite Hitler’s onslaught, the ghastly memories of World War I remained as fresh as ever—the sights and sounds of exhausted armies shadowboxing from their trenches; the tedium of siege and the billowing clouds of dense, roiling smoke; and the stabbing bursts of gunfire that never seemed to fade away. America had buried over 117,000 soldiers in World War I, while Europe and Russia lost 10 million. Many Americans thought that was plenty, and two decades later they had little appetite for what they still thought of as Europe’s wars. By the summer of 1939, with Europe bounded by France’s Maginot Line against Germany in the west and the provisions of the Munich agreement in the east, Roosevelt had all but decided not to run for a third term.

But then came a stark phone call at 2:50 a.m. on August 31, 1939, informing him that ten armored German divisions had stormed across the Polish border, and that war had been declared. Roosevelt cleared his throat and rasped to his ambassador in Paris, William Bullitt, who was relaying the news from Warsaw, “Well, Bill, it has come at last. God help us all.” It was then that Roosevelt began the process of reversing himself: he would ultimately decide to seek an unprecedented third term in office—breaking a tradition begun by George Washington himself. Over the next eight months, during the period known as the phony war, Roosevelt publicly promised to keep America out of Europe’s conflict. “I’ve said this before and will say this again,” he told the nation; “your boys will not fight in foreign wars.” Anyone who suggested otherwise was perpetrating a “shameless and dishonest fake,” the president said, adding, “The simple truth is that no person in any responsible place has ever suggested the remotest possibility of sending the boys of American mothers to fight on the battlefields of Europe.” Still, he also did what he could to nudge Washington and indeed the nation at large closer to action and to the growing reality of future conflict. But whereas Churchill had lectured Neville Chamberlain about his policies of appeasement (“The government had to choose between shame and war,” he bellowed. “They chose shame and will get war!”) Roosevelt instead searched for a middle way. He informed members of the Senate Military Affairs Committee that if England and France fell, all of Europe “would drop into the basket of their own accord. . . . I cannot overemphasize the seriousness of the situation. This is not a pipe dream.”

When Great Britain declared war on Germany, followed by France five hours later, Roosevelt took to the airwaves in a fireside chat, and said: “This nation will remain a neutral nation, but I cannot ask that every American remain neutral in thought as well. Even a neutral has a right to take account of facts.” And though he told Congress in a personal address, “Our acts must be guided by one single hardheaded thought—keeping America out of war,” he emphasized the urgency of repealing the Neutrality Act so that America could provide military support to the western Allies. (Congress responded by authorizing a so-called cash-and-carry plan, which allowed American manufacturers to sell arms to Britain and France so long as each country paid cash and sent its own ships to pick up the goods.)

Still, neutrality had a high price. The war news haunted Roosevelt. While poring over cables from abroad, or reading his morning New York Times and the Herald Tribune, he would mutter to himself over and over, “All bad, all bad.” The first president to use the phone extensively—Harry Truman recalled how Roosevelt’s voice boomed so loudly he had to hold the phone away from his ear—he often spoke to his emissaries in Europe or aides in the State Department. Day-in and day-out, the phone rang constantly, bringing him the latest news of Hitler’s feints and moves. Then his days were filled with meetings: with the press, with the secretaries of state and the treasury, with the attorney general, with his personal secretary for afternoon dictation, and ever more frequently with senior members of the Senate. Invariably, Fridays were cabinet days, when the president met with the members who had the greatest political weight or the greatest measure of influence.

Predictably, he craved diversion where he could find it—in his nightly rubdown with masseur George Fox, in his collection of stamps and cherished naval prints, in his beloved tree plantings, in his frequent naps, in the movies he was “addicted to,” and most of all in the cocktail hour that took place every afternoon at the White House, when he banished all talk of war and busied himself with mixes and shakers. But none of this was ever quite refuge enough.

“I’m almost literally walking on eggs,” Roosevelt confessed early in 1940. The strain showed. The president’s blood pressure shot up to 179/102. Then came a scare: one evening in February, during an intimate dinner with Ambassador Bullitt and the close presidential aide Missy LeHand, Roosevelt collapsed at the table—it was a small heart attack, which his longtime attending navy physician, Admiral Ross McIntire, quickly dismissed and hushed up.

AS SPRING APPROACHED, THE United States made one last-ditch effort to forestall all-out war. In March, Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles, a close adviser to the president, traveled to London, Paris, Berlin, and Rome to propose a plan of peace and security through disarmament. In hindsight, the proposal reeked of desperation. At the time, the Germans were scornful and the British were horrified. As the world watched, the United States seemed to be doing little more than awaiting Hitler’s next move.

It would not have to wait long.

On May 10, 1940, Hitler launched his now infamous blitzkrieg—lightning war—against the Netherlands and Belgium, ravaging them by land and air. On day four of the German advance, Hitler ordered the old Dutch city of Rotterdam destroyed not for military reasons but for Schrecklichkeit (“frightfulness”)—the explicit use of terror to break a people’s will to resist. After a day of ferocious bombing, some thirty thousand people lay dead beneath the rubble. Hours later, the Dutch surrendered unconditionally, and the Belgians followed within two weeks.

Then Hitler, unencumbered, turned his full force on France. Protected by Stuka dive-bombers, Nazi tanks and motorized infantry ripped through the Ardennes virtually unopposed, and Erwin Rommel’s notorious panzers rapidly reached the Channel coast. In World War I, movement of the battle lines was often measured in yards rather than miles, and the French and British had managed to hold back German thrusts for four ghastly years, despite the carnage and millions of casualties. This time, the French, considered to have the best army in the world, were dumbstruck. They were overrun and had hardly fired a shot.

Churchill urgently cabled to Roosevelt: “The scene has darkened swiftly. The small countries are simply smashed up, one by one, like match wood. We expect to be attacked ourselves.” Privately, Roosevelt told his aides that if Great Britain fell, the United States would “be living at the point of a gun.” The question for Roosevelt, however, and for the world, was this: was he willing to publicly rally the nation to brave the German fury? His answer was silence.

Within weeks, German panzer units had trapped the British expeditionary force and the French First Army along the harsh English Channel on the French beach at Dunkirk. While the German officers waited for Hitler’s final orders to annihilate the British, about 338,000 English and French troops escaped in an armada of small fishing boats and other craft, leaving behind nearly 2,500 guns and 76,000 tons of ammunition. Half of the British naval fleet, including its destroyers, had been sunk or damaged, and now England, fearing the worst, braced itself for an attack. Expecting the Germans to follow his troops across the Channel, Churchill proposed laying poison gas along England’s southern beaches to try to thwart the Nazi forces at the shore.

Then on June 5, German forces prepared to turn south. At the Somme, the French line crumpled before the onslaught of German panzers. Four days later, the Germans crossed the Seine, facing only token resistance. On June 14, the unthinkable happened: Paris itself fell. France was now finished, and its tattered government hastily retreated to Bordeaux. An armistice was signed on June 22, ceding a vast part of France to the Germans. The south of France remained in the hands of a puppet government in the resort town of Vichy. Meanwhile, the countryside was filled with refugees—and littered with corpses and the abandoned carts and luggage of the dead. Moreover, the Germans held 2 million French POWs.