Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

• Investigates the tales of Crowley “raising Pan,” going mad, and working gay sex magick in Paris

• Uncovers Crowley’s involvement in the Belle Époque with sculptor Auguste Rodin and other artists and in the 1920s with Berenice Abbott, Nancy Cunard, Man Ray, André Gide, and Aimée Crocker

• Reveals Crowley’s “expulsion” from Paris in 1929 as a high-level conspiracy against Crowley

Exploring occultist, magician, poet, painter, and writer Aleister Crowley’s longstanding and intimate association with Paris, Tobias Churton provides the first detailed account of Crowley’s activities in the City of Light.

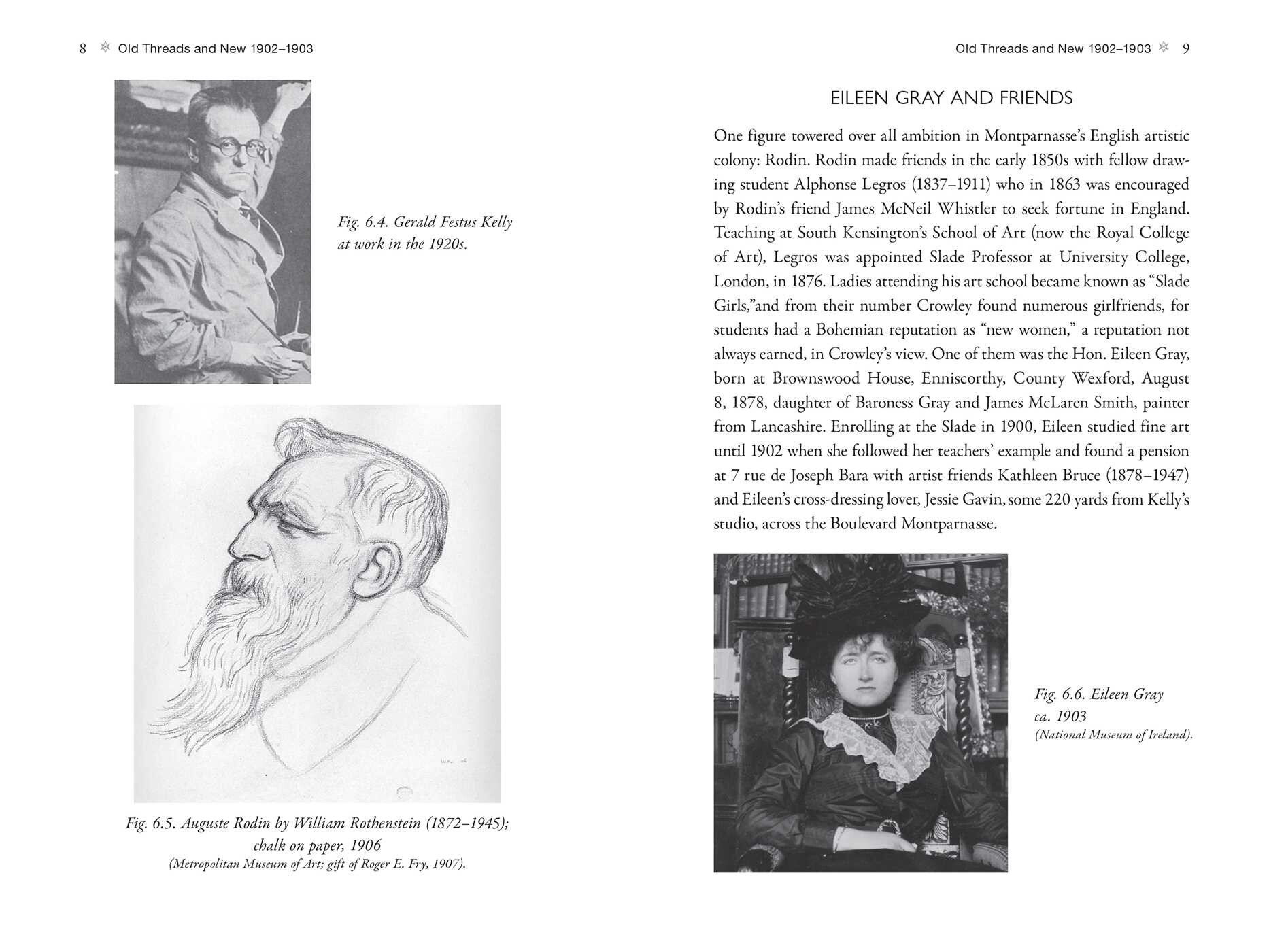

Using previously unpublished letters and diaries, Churton explores how Crowley was initiated into the Golden Dawn’s Inner Order in Paris in 1900 and how, in 1902, he relocated to Montparnasse. Soon engaged to Anglo-Irish artist Eileen Gray, Crowley pontificates and parties with English, American, and French artists gathered around sculptor Auguste Rodin: all keen to exhibit at Paris’s famed Salon d’Automne. In 1904—still dressed as “Prince Chioa Khan” and recently returned from his Book of the Law experience in Cairo—Crowleydines with novelist Arnold Bennett at Paillard’s. In 1908 Crowley is back in Paris to prove it’s possible to attain Samadhi (or “knowledge and conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel”) while living a modern life in a busy metropolis. In 1913 he organizes a demonstration for artistic and sexual freedom at Oscar Wilde’s tomb. Until war spoils all in 1914, Paris is Crowley’s playground.

The author details how, after returning from America in 1920, and though based at his “Abbey of Thelema” in Sicily, Crowley can’t leave Paris alone. When Mussolini expels him from Italy, Paris becomes his home from 1924 until 1929. Churton reveals Crowley’s part in the jazz-age explosion of modernism, as the lover of photographer Berenice Abbott and many others, and how he enjoyed camaraderie with Man Ray, Nancy Cunard, André Gide, and Aimée Crocker. The author explores Crowley’s adventures in Tunisia, Algeria, the Riviera,his battle with heroin addiction, his relationship with daughter Astarte Lulu—raised at Cefalù—and finally, a high-level ministerial conspiracy to get him out of Paris.

Reconstructing Crowley’s heyday in the last decade and a half of France’s Belle Époque and the “roaring Twenties,” this book illuminates Crowley’s place within the artistic, literary, and spiritual ferment of the great City of Light.

Excerpt

Samuel and Moina Mathers were busy moving from avenue Mozart to new (cheaper) accommodation in Montmartre when Crowley reappeared in November 1902. By that time the Isis performances probably felt to Mathers like a lost paradise. Since then, his world had fallen about his ears; Crowley’s, despite despairs, had grown.

According to Crowley’s Confessions, Mathers still commanded allegiance as “representative of the Secret Chiefs,”1 but having mulled over Bennett’s doubts over “integrity,” with added suspicion that Mathers was either temporarily “obsessed” by forces emanating from the book of the Sacred Magic of Abra-Melin, or had permanently “fallen,” Crowley’s Order commitment was inertial, partially compensated for by an intellectual Buddhism. Still, having consulted with Mathers last time he’d been in Paris, it seemed logical to rejoin the thread, and so he went, ostensibly to recover bags and books left when leaving for America two and half years before.

Surrounded by turmoil, Mathers appeared reticent, which Crowley attributed to embarrassment. Mathers had almost certainly sold Crowley’s bags, including an “almost new fifty-guinea dressing case.”2 Mathers handed over the books but said the bags he’d have to search for. Crowley watched as Mathers did to him what he knew he’d done to others: taken and not returned. But if the Chiefs had discarded Mathers, Crowley (he says) knew no replacement; the issue rankled.

It was probably Gerald Kelly who introduced Crowley to former Peterhouse, Cambridge student, Hugh Stephen Haweis (1878–1969), son of Rev. Hugh Reginald Haweis (author of Music and Morals, 1871) and artist Mary Eliza Haweis. Ensconced in Montparnasse’s English artist colony, Haweis, like Moina Mathers nearly a decade earlier, attended the Académie Colarossi where in 1902 he met artist Mina Loy and, venturing into forested Meudon on Paris’s southwestern outskirts, acquainted himself with controversial sculptor Auguste Rodin. Rodin invited Haweis to photograph his work. Haweis’s application of Steichen’s gum-bichromate process to the images captivated the sixty-two-yearold: “Mieux que Steichen,” Rodin exclaimed.3 Crowley noted some two decades later, “the youth”—in fact Haweis was less than three years his junior, and a Cambridge contemporary—had achieved “a certain delicate eminence,”4 which, whatever Crowley may have thought it meant, sounds patronizing, with a hint of envy. In 1904, Rodin made Haweis and Coles his official photographers.

According to Confessions, desire for an independent view on Mathers made Crowley ask Haweis to visit Montmartre, which he did, only to return with a tale of Mathers boring him with a disquisition on the gods of Mexico. Recognizing this as something Mathers picked up from the people who’d first “induced me to go out to Mexico,” Crowley smelled “charlatan,” “exploiting omne ignotum pro magnifico like the veriest quack.”5 Crowley here exploits a phrase uttered by Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes in “The Red Headed League” (Strand magazine, August 1891) that liberally transliterated means “everything unknown seems magnificent (to the ignorant).” Again, the implication is that Mathers aggrandized himself with stolen goods, which worked for him until someone recognized “the trick.” Confessions states that the “moment” he realized it, he came into contact with Mathers’s “forces.” Using Captain Fuller’s account written eight years later (Equinox 1, no. 4 (1910): 174–77), Crowley removed himself from whatever facts, if any, underlay what allegedly happened next.

According to Fuller, Crowley found Gerald Kelly perturbed. Enquiry revealed that vampire sorceress “Mrs M,” was manipulating a “Miss Q.” Crowley asked to visit Miss Q where Mrs M was living. Alone with Mrs M while Miss Q made tea, Crowley examined a bronze head of Balzac. While examining it, he felt dreamy and noticed Mrs M no longer appeared worn by middle age but as a bewitching beauty leaning over him, hair dangling seductively. Crowley allegedly got up, calmly replaced the bronze, and talked normally while mentally confronting her wiles with magical resistance. She tried harder, approaching with obsessing lust. Crowley’s resistance apparently confronted her with the hell of her own future decrepitude. She tried an obscenity and a kiss, but Crowley held the siren at arm’s length, netted in her own evil energy. Blue-greenish light seemed to envelope her head as what was now a hideous hag hobbled hopelessly from the room. Wanting to know if the vampire worked alone or was directed, Crowley supposedly asked Kelly if he knew a clairvoyant. He said he did: the “Sibyl.” The Sibyl eventually envisioned a house Crowley recognized as Mathers’. Entering the vision, Crowley found within it not Mathers and wife but what looked like Theo and Mrs. Horos: “Their bodies were in prison; but their spirits were in the house of the fallen chief of the Golden Dawn.”6

Crowley couldn’t tell whether to direct a hostile will-current against Mathers and Moina for inviting the spirits into themselves, or to see the figures as disguised Abra-Melin demons. Should he warn Mathers of evil done about him? The Sibyl responded to an inner voice: leave it alone. Crowley reflected years later in Confessions that this “story” was typical of his magical state at the time. He could function as a “Master of Magick” but wasn’t really interested. He thought he might complete Abra-Melin, but the mess over Mathers soured the proposal.

Inclined to Buddhism, Crowley published in Paris an edition of Berashith, written in India. Berashith portrayed Buddhism as essentially a science of mind elaborated into moralistic dogma. Years later, Crowley wondered if he hadn’t become rather big-headed on the strength of his adventures; he implies he had. Anyhow, “the big people in the artistic world in France accepted me quite naturally as a colleague.”7

Product Details

- Publisher: Inner Traditions (December 20, 2022)

- Length: 384 pages

- ISBN13: 9781644114803

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“This final installment of Churton’s expansive and detailed exposition on Aleister Crowley’s life, work, and milieu is a treasure trove of new information and startling revelations. Scrupulously researched and exquisitely written, Churton’s complete six-volume biography of Crowley confirms his position as one of the most insightful, respected, and eloquent scholars on Frater Perdurabo to ever put pen to paper. Aleister Crowley in Paris is a delight.”

– John Zorn, composer

“The young Crowley was in with the ‘in crowd’ in Paris and knew everyone it seems, who then, like him, became one of the characters that creatively shaped the last century. He was engaged to the great Eileen Gray, and lots of other notable women come to life in this very accomplished biography. Tobias Churton is to be applauded for once again getting rid of the gossip and giving us the facts, this time in ‘gay Paree,’ of the life and aspirations of the greatest magician of the twentieth century.”

– Geraldine Beskin, co-owner of the Atlantis Bookshop, London

“Tobias Churton’s multivolume work examining Crowley’s life and work in key geographical locations is nothing less than brilliant. This time Churton takes us to Paris, an extremely important place for Crowley. It’s a pure joy to travel alongside both Crowley and Churton to the City of Light and Romance and to indulge in both the scandals and miracles of the Great Beast 666.”

– Carl Abrahamsson, author of Source Magic, Anton LaVey and the Church of Satan, Occulture, and Reason

“Aleister Crowley in Paris recasts the Beast’s biography through the lens of Belle Époque Paris, where its expat embrace of freedom, art, publishing, magick, and romance captured Crowley’s heart. We find the mage returning over the years, seeking fresh inspiration or a safe haven from his woes, whether personal or magical. Throughout this engaging narrative, Churton proves that we cannot understand Crowley without understanding his relationship to Paris.”

– Richard Kaczynski author of Perdurabo and editor of Crowley’s The Sword of Song

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Aleister Crowley in Paris eBook 9781644114803