Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

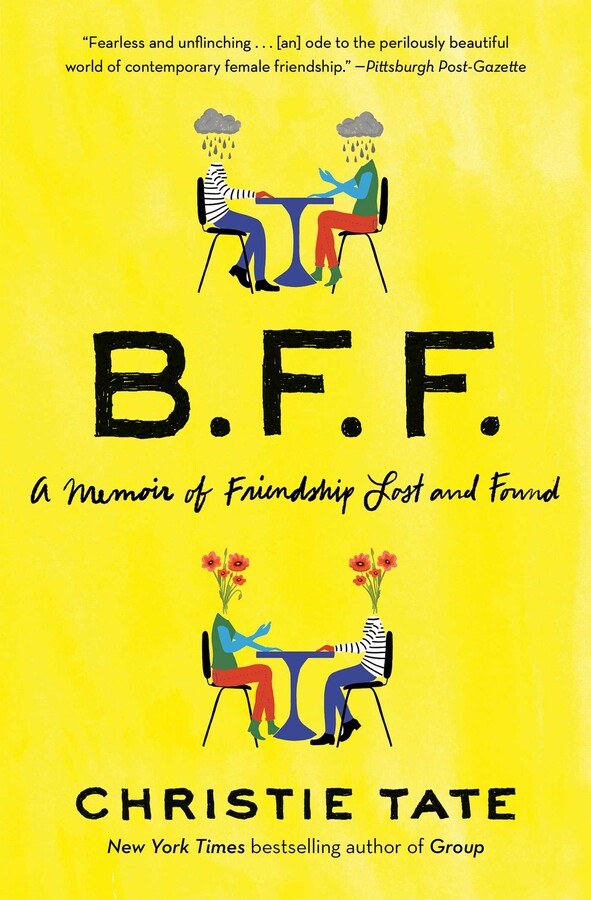

From the author of Group, a New York Times bestseller and Reese’s Book Club Pick, a poignant, funny, and emotionally satisfying memoir about Christie Tate’s lifelong struggle to sustain female friendship, and the extraordinary friend who changed everything.

After more than a decade of dead-end dates and dysfunctional relationships, Christie Tate has reclaimed her voice and settled down. Her days of agonizing in group therapy over guys who won’t commit are over, the grueling emotional work required to attach to another person tucked neatly into the past.

Or so she thought. Weeks after giddily sharing stories of her new boyfriend at Saturday morning recovery meetings, Christie receives a gift from a friend. Meredith, twenty years older and always impeccably accessorized, gives Christie a box of holiday-themed scarves as well as a gentle suggestion: maybe now is the perfect time to examine why friendships give her trouble. “The work never ends, right?” she says with a wink.

Christie isn’t so sure, but she soon realizes that the feeling of “apartness” that has plagued her since childhood isn’t magically going away now that she’s in a healthy romantic relationship. With Meredith by her side, she embarks on a brutally honest exploration of her friendships past and present, sorting through the ways that debilitating shame and jealousy have kept the lasting bonds she craves out of reach—and how she can overcome a history of letting go too soon.

“An outstanding portrait of self-excavation” (Publishers Weekly, starred review), BFF explores what happens when we finally break the habits that impair our ability to connect with others, and the ways that one life—however messy and imperfect—can change another.

Excerpt

I met Meredith in December 1998, and I still remember her outfit. A red blazer, multicolored silk scarf, gold pin. Black leather shoes with a kitten heel. A pencil skirt. Boniest ankles you ever saw. Her hair was blond with a few gray streaks, and her manicured nails were a pale pink that today I could identify as Essie’s Ballet Slippers. She stacked multiple rings on several fingers of both hands, which clacked softly when she gestured. Later, I told her she’d looked like a meteorologist from the eighties with that scarf and pin. “I was jealous of how put together you were—the outfit, the manicure.” At the time, I was twenty-five years old; Meredith was in her mid-forties.

We met at a recovery meeting held in the back booth of a Swedish diner on the North Side of Chicago. The purpose of the meeting was to help the friends and family members of alcoholics—anyone who loved a drunk, basically—reclaim their lives from the chaos of being intimately involved with someone who drinks too much. People had been recommending this recovery program to me for many years—starting with a biology teacher in high school who knew I was dating a basketball player who liked to party—and I’d refused, even though I spent half a dozen biology classes crying over the basketball player’s infidelity and nonstop pot smoking. No, not for me. Sophomore year of college, I found my way to a different twelve-step program, one for people with eating disorders, and it helped me address the bulimia that had dogged me since I was thirteen. One recovery program was enough, thank you very much.

I’d finally decided to walk through the doors of the weird Swedish diner meeting when Liam, my boyfriend at the time, came home yet again from the bar and puked in the toilet, too blitzed to say his name, much less Goodnight, Christie, or I love you. Sex was most certainly out of the question. In those days, I spent my waking hours perseverating over the question of why Liam would pick a six-pack of Schlitz over hanging out with me, wonderful me, who was turning into an emotionally bankrupt shrew whose primary job was to tally how much he was drinking and how little we were fucking. I’d become an abacus: all I could do was count how much he drank and all the ways he disappointed me. The night before my first meeting at that Swedish diner, I’d decided there was no harm in checking out another twelve-step meeting. Meetings typically last sixty minutes, and I wasn’t terribly busy with my secretarial day job and my nighttime job of waiting for Liam to tap into some desire for me. Maybe the people at this meeting could teach me how to get my beloved to stop drinking until he blacked out.

At the time, I lived and worked on the South Side of Chicago, in Hyde Park, one hundred blocks away from the Swedish diner in Andersonville. The morning of the meeting, I woke up before six to shower, dress for work, and pack food for the day, because as soon as the meeting was over, I’d have to bolt to my Honda and book it one hundred blocks back to Hyde Park, where I worked as an administrative assistant to a prominent social sciences professor at the University of Chicago. My job entailed sending faxes, answering the phone, and tracking down my boss’s speaking fees—tasks an average sixth grader could have executed. The boss wanted me there by 9:00 a.m. sharp in case the president called at 9:01 a.m. inviting him to discuss his research at an upcoming U.N. conference.

When the diner meeting started, only five other people huddled around the table in the back corner. “Hi, I’m Meredith. Welcome. We’re a small meeting,” said a smartly dressed woman when she saw me looking around for more people. My recovery meetings for bulimia took place in hospitals and churches—solemn institutions that smelled like antibacterial soap, mold, or incense—where we sat in folding chairs or on lumpy couches. Meeting in public at a table beneath stenciled images of old-timey Swedish townspeople, I felt exposed. What if I burst into tears? What if a member of the public overheard me talking about my boyfriend’s beer tab? What if someone I knew walked in for lingonberry pancakes before work? If Meredith hadn’t spoken to me, I would have turned around and walked out.

The person in charge, seated to the right of Meredith, had short, spiky brown hair and brick red lipstick. She introduced herself as Sherri and read from pages in a blue binder. At some point, she asked if there were any newcomers. I raised my hand and said my name. Around the table, each person said “Welcome” and smiled at me. My eyes filled with tears without my permission. These people—four women and one guy—were already paying more attention to me than Liam had over the past week. Underneath the table, I picked my cuticles, a terrible habit that left my skin tender and blood-streaked. I worried that after the meeting, one of these people would pull me aside and tell me I had to break up with him, or corner me and insist I stay. I blinked and blinked, trying to keep the tears from falling.

Throughout the hour, I bobbed along the bottom of my pain, pining for the early, blissful days of my relationship with Liam when we dated long-distance: I had lived in D.C., he in Chicago. He wrote me a letter every single day, and during our monthly visits, we’d spend the weekend in bed, laughing, dozing, and getting to know each other. In our long-distance year, I rarely saw him drink, and never once saw him drunk. But since I’d moved to Chicago to be with him, he changed jobs and began working sixty-hour weeks at a consulting firm. The drinking surely relieved the pressure of his job, as well as the strain of my constant surveillance of his alcohol consumption. A few beers took the edge off my weekly reminders about how long it had been since he’d bothered to fuck me.

I prayed one of the people who’d welcomed me to the meeting would tell me how to make the drinking stop. No one offered anything close to a quick tip; there were no hacks, only suggestions that we look at our own lives. Take the focus off the alcoholic, more than one person said, which I thought was dumb because my only problem was Liam’s drinking. There were, of course, several items in my own life I was ignoring every time I fastened my laser focus on Liam’s affinity for beverages in brown bottles, such as my dead-end job that didn’t cover my mountain of student debt; my dusty-ass apartment that lacked central air and a single free inch of kitchen counter space; and my distant relationships with every other human being on the planet. I sure as hell couldn’t see that this consuming “romance” with my boyfriend had crowded out my friendships. Every single friend had gone blurry in my peripheral vision. One minute they were there, and then: vanished.

When I met Liam, I was part of a trio of friends in the same master’s program in humanities at the University of Chicago. Amy, Saren, and I ate lunch together every day on campus, discussed the readings we did for our classes, planned dinner parties, and piled in Saren’s car for shopping trips to the suburbs. We had inside jokes about our professors and the eccentric characters in our graduate program, like the woman who could not have a conversation without quoting Bertolt Brecht. We’d met each other’s parents, and when we talked about the future beyond graduate school, we assumed our friendship would remain in the center of our lives. But when I started dating Liam right after graduation, I let the friendships wither, quickly and fatally. And it wasn’t because I was too busy and blissed out from the hot sex to join my friends for Thursday-night must-see TV or sushi downtown. Liam was in our graduate program; we could have all hung out together. But I was threatened by Amy and Saren—I didn’t drink and they did, so they were livelier and looser than I was. I couldn’t have admitted it at the time, but I feared Liam would compare me to them and realize he’d mistakenly chosen the uptight teetotaler who liked to go to bed by nine thirty after spending the day battling low self-esteem and anxiety. They were a better match for him, especially Saren. She’d read everything, drove a red Bronco, and wore trendy, belted outfits. She also had an impressive job lined up with a Chicago magazine. The one time we went out as a group, she and Liam had a long, heated conversation about Studs Turkel and postcapitalism poverty in Chicago. From their reddened cheeks and loud voices, I could tell they were buzzed, energized. They looked like they wanted to mash their lips together. My sole contribution to the forty-five-minute conversation was “I heard they’re tearing down Cabrini-Green.” To me, the vibe between them was unmistakable, but instead of having an honest conversation with them or asking Amy for a reality check, I withdrew from the friendships, backing Liam and myself into an isolated corner so no one could see how mismatched we were.

I cut Amy and Saren out of my life with little remorse. I cared only about my faltering relationship with Liam. And it was a vicious cycle: I dumped my friends and became more isolated, which made me hold on to the unhealthy romance even tighter, because there was no else around. I lost my friends and myself, as Liam became the subject of most of my sentences. He’s under so much pressure at work. He screamed at me the other night about a coffeepot that he left on. He likes to drink at the dive bar on Oakley.

Maybe if I’d held on to the friendships, Amy and Saren could have helped me sort out my relationship. If I’d let them, they could have had a close-up view of what was happening to me and asked questions. Are you happy in this relationship? Is this working? Why are you holding on so tightly? They could have pointed out that I had no plan for the future and less than $30 in savings. They could have helped me find an apartment that didn’t make me want to die in my sweaty sleep when the temperature rose above 85 degrees.

If I’d had close friends, I would have turned to them instead of this random collection of people sitting at a diner talking about alcoholism.

During the meeting, I watched Meredith. And I listened. She talked about her mother and her sister, and I tried to figure out which one drank too much. She leaned forward when she talked, making eye contact with everyone. In her three-minute share, she mentioned having a sponsor, working the steps, and surrendering to a Higher Power. The holy trifecta of recovery meetings. By the end, I sized her up as a wise elder. She slid out of the booth five minutes before the meeting ended. “Work meeting,” she whispered to the woman sitting next to me. Her heels click-click-clicked against the diner’s tiled floor.

In Meredith, I didn’t see a friend, a confidante, a sponsor, or a sister. I didn’t have that kind of imagination. I saw a wise middle-aged woman who liked gold rings and spent her days at an important day job, where she wore blazers and managed a staff. I never dreamed we’d talk on the phone, cry on each other’s shoulders, or become each other’s family. I saw no common ground between her pain with her mother and sister and my devastation over my boyfriend’s drinking.

Anyway, I wasn’t looking for friends. I had my hands full trying to get Liam to cork the bottle and pay attention to me. He was my first great love, and I couldn’t bear the thought of living without him. If only I could get him sober, I’d have the perfect life.

Reading Group Guide

Get a FREE ebook by joining our mailing list today! Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

Introduction

Christie Tate proved herself to be a master at laying bare the messy shames of her own psyche with her New York Times bestselling debut memoir, Group, and her knack for excruciating vulnerability is at the forefront of B.F.F. Here, we learn about the fraught family history and destructive jealousy that would follow Tate into adulthood, as well as meet the cast of characters with whom she falls in and out of friendship throughout her life. Chief among them is Meredith, a woman Tate meets in recovery who becomes her cheerleader and fellow commiserater in a shared journey to stronger female friendships. Over decades of morning diner dates, desperate texts, and seismic life events, Tate and Meredith navigate their debilitating insecurities and regrets of friendships past, working together to transform their relationships with women. When Meredith is diagnosed with cancer, Tate honors her by striving to be the friend she deserves until her final days. B.F.F. is a razor-sharp and delightfully funny interrogation of the blind spots that plague us all, as well as a deeply heartwarming book that asks how we can strive to show up for the people we love most.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

The prologue describes Tate giving a eulogy at Meredith’s funeral. How would your experience of B.F.F. have been impacted had Tate simply begun with meeting Meredith in chapter 1—in other words, if you didn’t know that Meredith would die by the book’s end? What is gained with that knowledge?

Excavating her childhood friendships—as well as her relationship to her sister—is a vital part of Tate’s healing work. How does Tate’s approach to friendship evolve from the playground to Catholic school to college and beyond? How is her family life and dynamic with men inextricable from this? Can you identify similar patterns in your life?

In chapter 6, Tate experiences a turning point in the way she thinks about shame, “apartness,” and friendship. How does Tate build tension during the scene at dinner, and after? Have you ever had a similar moment of realization?

At the end of chapter 14, Meredith asks Tate to “write a vision for ourselves in friendship . . . a map for where we’re going (100).” Try this exercise yourself. What do you discover?

B.F.F. covers trauma, mental illness, sickness, and death—yet the tone of the book isn’t heavy or dour. How would you describe Tate’s sense of humor? How does it impact your reading of the book, especially the more difficult topics?

Consider the questions Tate asks herself after seeing Meredith for the last time (232). Do any of them resonate with you?

Tate divides B.F.F. into three sections: “Part I: What It Was Like,” “Part II: What Happened,” and “Part III: What It’s Like Now.” How does this structure orient you in Tate’s story? Reflect back on how Tate evolves over the course of the book. In your opinion, what are some of her most significant moments of growth?

Think about the major friendships Tate dramatizes in B.F.F.—for example, with Lia, Callie, and Anna. Which did you find the most emotionally or narratively compelling? Why do you think that is?

B.F.F. ends with a series of letters addressed to Meredith that chronicle Tate’s continuing friendship journey. What is the rhetorical effect of this? Are there any achievements in the letters that feel particularly triumphant for you?

If you could distill three lessons that Tate learns in B.F.F., what would they be? What will you take away from her story?

Enhance Your Book Club

As a group, brainstorm other memoirs and books that depict complicated female friendships. What do these selections share in common with B.F.F.? What did you appreciate about Tate’s specific story and approach?

Discuss some of the friend breakups Tate experiences throughout her life. Split up into pairs and assign roles—one person is Tate, while the other person is one of her friends. Using the context you learned from B.F.F., write a reconciliation conversation between the women and then present it to the group. What does each women have to atone for in order to remedy the relationship? How can you demonstrate character development?

It’s time to cast the B.F.F. movie or miniseries! Choose your top picks for Tate, Meredith, and the other friends in Tate’s life—and make a case to the larger group about who would best embody each character.

A Conversation with Christie Tate

What did you bring from your experience writing Group to your experience writing B.F.F.? On a craft level, how were the processes different? Did one feel scarier or more vulnerable to publish than the other?

When I first published Group, I thought there was no way any subsequent book would be as emotionally harrowing to write. What, I wondered, could be scarier than writing about all the bad sex I had during my twenties and early thirties? But within two weeks of starting B.F.F. I realized that it would be more vulnerable and terrifying to write about my relationships with women. The vulnerability at the center of Group revolved largely around my fears of intimacy with men, and it was easy to hide behind the emotionally unavailable boyfriends and compromising situations I put myself in. With friendship, I felt like there was no hiding; the friends I struggled to connect were loving and generous, if messy and wounded in many of the same ways I was. My behavior in friendship was so rarely conducive to building healthy bonds, and the trouble with friends started long before my trouble with boys, and it also lasted much longer. In truth, I struggle to this day with all the lessons I learned in the book—direct communication, boundaries, envy, and scarcity. Thus, I found that revealing my bad behavior as a friend, where I was often a perpetrator, felt much more vulnerable than my bad behavior as a girlfriend, where I perpetually saw myself as a victim. Moreover, I no longer have a relationship with any of the ex-boyfriends who appear in Group, but I’m still connected with most of the friends I write about in B.F.F. What could be more vulnerable than having ongoing relationships with friends who’ve seen me at my worst? Those friends—Callie, Anna, Lia—witnessed my behavior when I lacked the skills to do better and before I’d addressed my emotional blocks. To tell the world how I’ve faltered and then rehabilitated my role as friend to these incredible women who remain in my life is scarier than any tale of a bad blow job to a guy I’ll never seen again.

Did you have a method for writing the passages about your childhood?

Absolutely. First, I would convince myself that no one would ever read any of the passages I’d write. This was step one because I couldn’t possibly get the words on the page if I thought about my words one day appearing in a published book. Then, I made a list of all the scenes I couldn’t possibly write for all the reasons people avoid writing memoir: Someone might get upset, mad, or hurt. Someone might abandon me. I might not remember it correctly. I might be wrong. Then, one by one, I wrote those scenes as I remembered them, careful to include phrases to indicate to the reader that my memories, like all memories, were highly fallible. From there, I revised the scenes to ensure they reflected my experience and granted as much privacy as possible to the members of my family, especially those who are not keen to appear on the pages of my memoir. When I’d whittled the scenes down to the ones that were essentially for the story of B.F.F., I prayed, snacked, cried, gnashed my teeth, talked to other writers, threw rocks in Lake Michigan, discussed the project in therapy, and then finally: I lit a candle, prayed for the willingness to give myself permission to write what I needed to write with integrity, gratitude, honesty, and humility. Then, more snacks. I should probably give Trader Joe’s a cut of the profits.

Was there a particular moment or scene that was especially easy or pleasurable to write?

I loved writing about Meredith. Every time I found her on the page, I had the pleasure of spending time with her again. As I drafted scenes to highlight how complex, glorious, loving, and stubborn she was in real life, I felt her come alive. Even now, I remember where I was when I drafted the scene when I told her I’d ghosted Callie (in a hotel lobby in Las Vegas); when I wrote my first letter to her that appears at the end of the book (Harold Washington Library, fourth floor); and when I wrote about the day I visited her in the hospital (at my dining room table). The pure joy of writing those letters was a total surprise and a full-body joy infusion that I’d never experienced in writing before or since.

What about one that was particularly difficult or fraught?

Writing about attending a recovery meeting with my family as a little girl was as fraught as any scene I’ve ever written in my life. Ten times harder than any sex scene. When writing about someone else’s recovery, I have to balance the needs of the story with my family member’s right to anonymity and privacy. With B.F.F., I couldn’t tell the story of why I struggled as a friend without telling the story of how I struggled as a sister. And that scene—where I heard my dad call my sister a “miracle” in a recovery meeting, solidifying my deep feeling of inferiority because he didn’t also call me a “miracle”—had to be in the story. There were moments early on during the drafting when I thought I couldn’t write this book because I didn’t know if I had the courage to navigate all the tender relationships and ethical principles involved in writing about someone else’s recovery. Even writing this recap makes me feel tingly with anxiety.

Since the hardcover publication of B.F.F., have you experienced any new facets to your friendships that you would like to explore in future writing? Do you have any new friendship goals for yourself?

Yes! I would like to explore my friendships with men, which is a question I fielded from many readers: What about your friendships with men? Every Wednesday for the past few years, I’ve met up with two male friends at a coffee shop near my house—during the pandemic we sat outside, shivering and sipping coffee under our masks. I protect that time the same way I protect my therapy time and family time. We get our lattes and then we gossip, dissect our spouses’ foibles, debate the merits of Succession and the merits of Richard Marx’s discography. I notice that with these two men, I don’t have the same neurotic fear of being in a friendship triangle. I’m still teasing out what makes these coffee dates different than the ones I have with my girlfriends, where I’m still so obviously a work in progress. As for friendship goals, they remain modest: Show up for my friends, and when I can’t, be honest about my limitations as soon as possible.

What do you think Meredith would think of B.F.F.?

Shortly after Meredith and I both saw a Chicago production Hamilton, we had a little tiff. I was angry that she was not standing up for herself at work. She kept insisting that she had to just suck it up because she was lucky to be employed at a world-famous treatment center. “You know what your problem is?” I yelled at her. “You think you’re a Peggy, but you’re an Angelica!”—referring to the two Schuyler sisters, one of whom is barely a footnote in the musical (Peggy), while the other gets to take center stage to rap about Ben Franklin and clamor for women’s rights. We’d been walking down Washington Street toward the redline train. She stopped and stared at me for a long moment, tears pooling in her eyes. “You really think I’m an Angelica?” I wanted to grab her by the neck and give her a noogie. Of course, she was an Angelica. She had a bazillion years of sobriety, made straight As in her master’s program, and had almost sixty years of experience to share with patients seeking relief from addiction. But she saw herself as the sister that no one cared about, the forgotten footnote. If she knew there was a book about her in the world, she’d be so shocked she’d laugh until she cried, and then cry until she was laughing again. She might even let me buy her a bottle of San Pellegrino. The big one.

If you could describe your ideal self in a friendship in five words or less, what would they be?

Christie: honest, messy, humble, willing.

What advice about friendship would you give young Christie? What about to a reader who finds themselves struggling to maintain lasting friendships?

To young Christie I would say: “Your friendships are just as important as your romantic relationships.” I’d point out that her rabid fixation on finding a suitable, long-term boyfriend—thank you, Patriarchy—was not serving her. She’d bat me away, but I’d double down and tell her that even though culture has convinced her that the only relationship that matters is the romantic one, culture is often deadly wrong (see: slavery, Japanese detention camps, miscegenation laws, Antisemitic zoning laws, mixing powdered French onion soup into sour cream to create a “fancy” dip for dinner parties). I’d whisper to her that she should figure out what’s blocking her from loving her friends with her whole, messy heart, and then encourage her to put her money, time, and energy into removing that block. “You deserve rich, intimate friendships, but they don’t just happen. You have to work for them. They are worth it.”

Product Details

- Publisher: Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster (March 14, 2024)

- Length: 320 pages

- ISBN13: 9781668009437

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“Fearless and unflinching. . . [an] ode to the perilously beautiful world of contemporary female friendship.” —Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

“A love story, an ode to those who shape our lives, and a close examination of one woman's inner battles in a humorous, approachable way, B.F.F. is definitely the book to give your own bestie, no matter what age.” —Zibby Owens, GMA

“Tate explores . . . memories and her adult friendships with the same vulnerability that made Group such a captivating read. She’s unafraid to share the unvarnished truth about her insecurities. . . B.F.F. is an openhearted examination of the power of friendship from people who love us exactly as we are.” —BookPage

"B.F.F. is a love story about the miracle of friendship. But it’s also an admirably vulnerable, heartbreaking-meets-funny self-interrogation. Reckoning with failed or faltering friendships—the ones that feel like auditions for a part you're desperate to play, or high-stakes competitions, or even love triangles—means reckoning with the kind of friend you are. It means facing yourself. B.F.F. made me laugh, cry, and cringe with recognition, page after page. It made me want to pick up the phone and start calling my friends." —Maggie Smith, author of You Could Make This Place Beautiful

"A meaningful, memorable journey from inner pain to honest, open, and enduring friendship.” —Kirkus Reviews

“In her heartfelt memoir, Tate reflects on the implosion of her past female friendships . . . [She] takes accountability for her actions (‘I’m a work in progress’), and she captures the transformative power of friendship . . . Readers will be moved by this outstanding portrait of self-excavation." —Publishers Weekly (starred)

“In close parallel to her debut, Group, Tate's second memoir is another long look at a lifetime's work of healing relationships . . . Written in three understandable, relatable parts—"What It Was Like," "What Happened," "What It's Like Now"—Tate's book shows readers how deep the work had to go for her to change.” —Booklist

"Tate catapulted onto the literary scene in 2020 with Group, a gorgeous, brave, vulnerable memoir about group therapy and all the ways it scared, shaped and saved her. . . B.F.F. carries that torch, and uses it to illuminate the unexpected, unexplored corners of friendship and isolation, belonging and insecurity." —Heidi Stevens, Tribune News Service

“Tate’s chaotic yet heartwarming first book [Group] was all about the unconventional group therapy setting that helped her work through her issues with intimacy. . . In her second memoir, Tate focuses on the elusive intimacy of friendship, recounting the tumultuous, emotional and funny process of learning how to have and be a friend. It yet again strikes that perfect balance of an author spilling the dirt and baring her soul.” —BookPage

SELECTED PRAISE FOR GROUP

"Every page of this incredible memoir, Group by Christie Tate, had me thinking 'I wish I had read this book when I was 25. It would have helped me so much!'... We need each other through the good times and the bad. Please read this book with a group of friends you cherish." —Reese Witherspoon

"Tate’s hard-won willingness to become loving and to be loved ultimately shapes a story that has a lot of heart—one that goes straight to the messy center of what it means to interrogate our own limitations and deepest desires, wherever that journey may take us." —Dani Shapiro, The New York Times

"Often hilarious and ultimately very touching." —People

“[Tate's] commitment to detail serves Group well. So does her plain determination to present herself not as a victorious therapy graduate... but as an ordinary woman who has been lucky enough to beat some extraordinary demons. Group is consistently determined and grateful, with an appealing strand of self-deprecation and a deep affection for [Tate’s groupmates].” —NPR

“Fearless candor and vulnerability.” —Time

"A wild ride. . . It gets pretty raw." —The Boston Globe

"It takes courage to bare your soul in front of a therapist, but when you add six strangers to the mix, it becomes an act of faith. In Group, Christie Tate takes us on a journey that's heartbreaking and hilarious, surprising and redemptive—and, ultimately, a testament to the power of connection. Perhaps the greatest act of bravery is that Tate shared her story with us, and how lucky we are that she did." —Lori Gottlieb, New York Times bestselling author of Maybe You Should Talk to Someone

“Eugene Onegin made me want to move to Russia and Little Women made me want to have sisters. Group made me want to rewind a decade, sit with a number of strangers and one shamanic doctor, strip down and survive. This unrestrained memoir is a transporting experience and one of the most startlingly hopeful books I have ever read. It will make you want to get better, whatever better means for you." —Lisa Taddeo, New York Times bestselling author of Three Women

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): BFF Trade Paperback 9781668009437

- Author Photo (jpg): Christie Tate © Mary Rafferty Photography(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit