Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

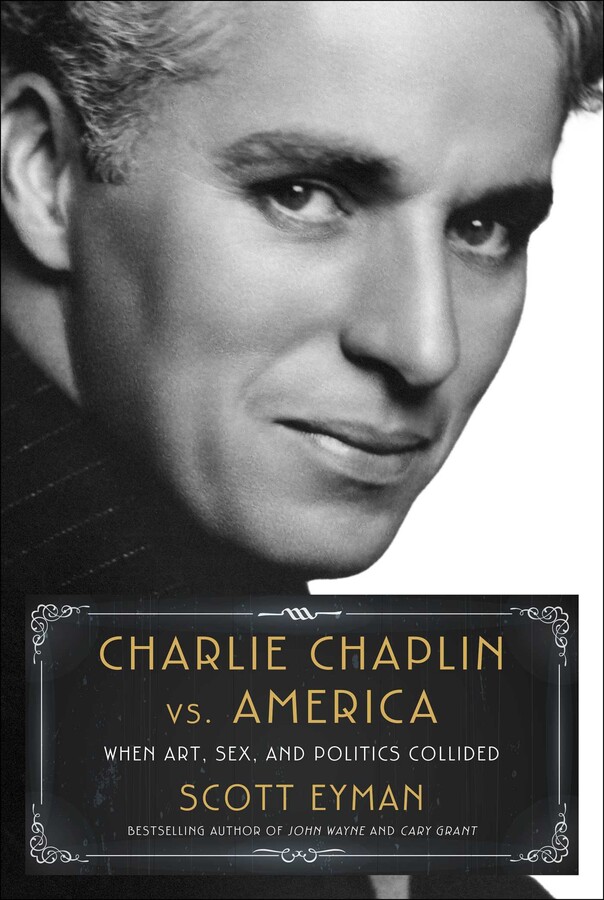

About The Book

Bestselling Hollywood biographer and film historian Scott Eyman tells the story of Charlie Chaplin’s fall from grace. In the aftermath of World War Two, Chaplin was criticized for being politically liberal and internationalist in outlook. He had never become a US citizen, something that would be held against him as xenophobia set in when the postwar Red Scare took hold.

Politics aside, Chaplin had another problem: his sexual interest in young women. He had been married three times and had had numerous affairs. In the 1940s, he was the subject of a paternity suit, which he lost, despite blood tests that proved he was not the father. His sexuality became a convenient way for those who opposed his politics to condemn him. Refused permission to return to the US from a trip abroad, he settled in Switzerland, and made his last two films in London

In Charlie Chaplin vs. America, bestselling author Scott Eyman explores the life and times of the movie genius who brought us such masterpieces as City Lights and Modern Times. This is a perceptive, insightful portrait of Chaplin and of an America consumed by political turmoil.

Excerpt

In those days, nothing important happened on the weekends.

Movie people went to parties, to Palm Springs, or to clubs on the Sunset Strip. Occasionally they paired off in a way they couldn’t during the week, when they had to get up before dawn in order to get to the studio by 8 a.m. And sometimes they just rested.

What this meant in practice was that a Monday gossip column was typically filled with soft items saved for a slow news day. Hedda Hopper’s column for Monday, May 19, 1952, was a case in point: “Ava had a party of 10 to put Frankie in the groove at the Grove. And [photographer] Hymie Fink covered him from every angle.… Phil Yordan’s ‘Edgar’ for the Detective Story screenplay was stolen from the detective bringing it to him by train. So Phil’s hiring a detective to find it.”

Hopper’s lead item seemed to fit right in: “Charlie Chaplin has his return visa and he’s all set for Europe in September for the preems of Limelight in London and Paris. Oona goes along, but the kids stay behind in Beverly.”

In fact, the item was not a space-filler so much as one of those barely perceptible tremors that precedes an earthquake. A day or two after the item ran, Hopper sent a clipping in a letter addressed to California Senator Richard M. Nixon:

My dear Dick,

The enclosed about Charlie Chaplin is very distressing. He tried to leave the country a year or so ago and was told he couldn’t get back in. I hope that situation has not changed. And if it has been changed and he has finagled through the State Department and has obtained a passport with re-entry, I believe it is the duty of each Senator to know about it.

Personally, I hope he goes and never comes back in. He is as bad a citizen as we have in this country, as you well know.

I hope you will look into this matter and do what you can about it.

For Nixon—or anybody else—Hopper was categorized as High Maintenance. She wrote Nixon dozens of letters of approval, as well as occasional scoldings when she felt that he came up short in attending to her needs. This invariably involved Nixon failing to placate her with a soothing “Dear Hedda” letter of reassurance about her vital contributions to their shared priorities.

On May 29, Nixon replied: “I agree with you that the way the Chaplin case has been handled has been a disgrace for years. Unfortunately, we aren’t able to do too much about it when the top decisions are made by the likes of [Secretary of State Dean] Acheson and [Attorney General James] McGranery. You can be sure, however, that I will keep my eye on the case and possibly after January we will be able to work with an Administration which will apply the same rules to Chaplin as they do to ordinary citizens.”

That paragraph aside, it’s a chatty letter between old friends. Nixon discusses the upcoming Republican convention and the tactics being deployed by Robert Taft and Dwight Eisenhower, the two main candidates for the nomination. Hopper was ardently for Taft, and Nixon didn’t disabuse her of the notion that he was as well, even though he would happily accept the vice presidential nomination from Eisenhower. Nixon had a hunch that the convention would not devolve into a destructive food fight. “I still think that we are going to come out of the Convention united behind a good candidate.

“Pat joins me in sending our best to you.”

Nixon had been a member of the House Un-American Activities Committee whose hearings had shaken Hollywood to its core in 1947, with Hopper serving as a primary cheerleader. They were devout coreligionists in the fight against the social decay represented by Communism, not to mention unchecked sexuality, and they believed Chaplin embodied both.

Hopper in particular had long regarded Chaplin as an affront to both her country and her movie industry—Hopper personalized all relationships. She had furiously sniped at Chaplin’s plans to make The Great Dictator and greeted its great success with sullen silence. In April 1947, when Chaplin’s film Monsieur Verdoux was meeting with critical contempt and public indifference, she wrote J. Edgar Hoover: “I’d like to run every one of those [Communist] rats out of the country and start with Charlie Chaplin.… It’s about time we stood up and be counted.”

Chaplin gave no indication that he was aware of the storm clouds forming on the horizon. On August 2, a few months after Hopper’s column item, Chaplin hosted a preview of Limelight at the Paramount studio. The guest list amounted to about two hundred people, including Humphrey Bogart, David Selznick, Ronald Colman, and Sylvia Fairbanks Gable—the elite of old Hollywood.

The only journalist invited was Sidney Skolsky. He reported that as the end titles faded, the audience stood up en masse and shouted “Bravo.” Chaplin stepped in front of the screen and said, “I thank you. I was very afraid. You are the first ones in the world to see my film, which lasts two hours and a half. I don’t want to keep you long, but I care to say ‘Thank You.’?”

A woman stopped him by shouting “No!! No! Thanks to you!” and the rest of the crowd started shouting “Thank You.”

The tumultuous response was soon confirmed by the response of the novelist Lion Feuchtwanger, who wrote Chaplin on August 8: “The film… arouses emotions much like Dickens’ novels. It moves without ever becoming corny, and, at the right moment, the legitimate emotion is mingled with a good, sound, legitimate laugh. Your picture is deeply human and in the best sense popular. So it accomplishes the mission which Molière requires of a real work of art; it satisfies and pleases the professor as well as the cook.”

The response to the preview must have assuaged some of Chaplin’s fears of obsolescence. After The Great Dictator, he had endured years of public castigation for his support for opening a second front to aid Russia during World War II while simultaneously enduring a definitively ugly, trumped-up paternity suit. After that, Monsieur Verdoux had been his first critical flop and, in America, a commercial disaster.

On the night of September 5, Chaplin was having a cup of coffee at Googie’s, a small café on Sunset Boulevard. Across from him sat his assistant Jerry Epstein. Some pictures turned out to be less than Chaplin had hoped (The Circus), and some turned out to be better than he had dreamed (City Lights) but he was calmly confident about Limelight. He was sixty-three years old, madly in love with his wife, Oona, the mother of four of his six children. He believed that his third act would be his richest, and he believed he knew why.

It was all about America.

“I could never have found such success in England,” he told Epstein that night. “This is really the land of opportunity.”

The next day, Saturday the 6th, he made a few last-minute trims in Limelight. As he left the editing room Chaplin insisted that Oona come with him to the Bank of America. He wanted her signature on a joint account. He explained that in case anything happened to him, she would have instant access to his cash and securities. Oona thought he was being silly. What could possibly happen? Chaplin insisted, and Oona did as he asked.

Later that day, Chaplin, Oona, and Harry Crocker, an old friend who had served, variously, as costar (The Circus), assistant director (City Lights), and publicity director (Limelight) left for New York on the Santa Fe Chief. A week later, the Chaplin children—Geraldine, Michael, Josephine, and Victoria—followed, along with two nurses.

The plan was to travel to England on the Queen Elizabeth for the world premiere of Limelight in London, and then take the family on a vacation through Europe. Chaplin wanted to show Oona his London: Lambeth, Kennington, the East End—the rooming house where he had lived with his father and his father’s mistress; the workhouse where he had been interned as an indigent child; the pub where he had seen his alcoholic father for the last time. After London and the Continent, they would return to Los Angeles within six months.

Chaplin had originally planned the trip for several weeks earlier, but Oona had fallen ill, and the trip was pushed back. Then Chaplin realized he had lost his passport, which entailed applying for a duplicate, wherein he asserted that the passport “might have been lost during rebuilding of my house.” That rebuilding was necessary because of the birth of his and Oona’s fourth child. The house at 1085 Summit Drive, just up the road from Pickfair, had been expensively expanded and reconfigured for his growing family.

Upon arriving in New York City, the Chaplins checked into the Sherry-Netherland. Oona called their friend Lillian Ross of The New Yorker, and invited her to go for a walk with Chaplin the next day. At eleven the next morning, Ross picked up Chaplin at his suite.

“Walking around the city is a ritual with me,” Chaplin explained. “I love to walk all over New York.”

Out on the sidewalk, Chaplin took a deep breath. It was close to autumn, but the day was warm. “I like this kind of day for walking in the city. A sultry, Indian summer September day. But do you know the best time for walking in the city? Two a.m. It’s the best time. The city is chaste. Virginal. Two a.m. in the winter is the best, with everything looking frosty. The tops of the automobiles. Shiny. All those colors.”

Chaplin began walking briskly, taking it all in. “You come along this avenue and you meet the world. In Hollywood, you walk for miles and you don’t meet a single friend. Sometimes when I have a whole day here I walk a whole day. I just go along and I discover places.… I used to go to Grand Central—to the Oyster Bar. I’d get a dozen clams, and all you’d want besides is the lemon. You’d get a dozen clams for eighty cents.…

“You know, in 1910, when I first arrived in New York, it was just this kind of a day in September. Indian summer. Funny thing. We got off the boat and had our luggage sent to the theater—to the Colonial Theatre, at 62nd and Broadway. The theater is gone now. I can conduct you on a tour. Tell you all about New York in 1910 and in 1912. I’ve outlived it all.”

On 42nd Street, Chaplin stopped and looked around. “There used to be a Child’s restaurant around about here. That Child’s was wonderful. It was all very white. They used to make hotcakes right in their window. Forty-second street was very elegant then. Very elegant.… What a meal you could get at Child’s for a quarter, plus dessert. Or two eggs, hot biscuits and wonderful coffee, all for fifteen cents.”

The day before Chaplin and his family were scheduled to leave for London, he called Richard Avedon. The photographer had been chasing him for years, but Chaplin hadn’t answered his letters. It wasn’t personal—Chaplin rarely answered letters. Avedon thought the call was a joke and hung up, but Chaplin was used to that response and immediately called back. “I’m coming over right now,” he told Avedon, who promptly sent all of his assistants out of the studio—he didn’t want any distractions.

At first, Avedon shot a few pictures straight on, “almost as though I was doing a passport picture.” When Avedon thought he had his shot, Chaplin asked, “May I do something for you?” He lowered his head, and came up grinning in extreme close-up, with his index fingers forming horns on the side of his head—the Great God Pan. Or, if you believed Hedda Hopper, Satan incarnate. Chaplin did it once more, and the second time was the keeper.

“I can’t take responsibility for this picture,” Avedon would write. “It was one of those perfect moments when the light was right, and I was there, and the sitter offered the photographer a gift… the kind of gift that arrives once in a lifetime.”

That night, Chaplin and Oona went to dinner with Lillian Ross and James Agee and his wife, Mia, at the Stork Club. Later, they went to 21.

On the evening of September 17, Chaplin and his family left for London on board the Queen Elizabeth. Years later, Chaplin remembered watching the Statue of Liberty recede into the distance as the ship sailed out of the harbor. “I thought to myself what it had meant to me when I first saw the statue. It filled me with tremendous joy. It meant freedom and progress in America. But when I looked at it that day on my way out to sea, I found myself wondering how accurate a symbol it really was.”

ONE DAY OUT of New York, Chaplin and his wife were having dinner with Harry Crocker, Adolph Green, and Arthur and Nela Rubinstein when a steward told Crocker there were four radio telephone calls for him. Crocker left the table to attend to the problem. The calls had come from newspaper reporters. They read Crocker a cursory press release from the Department of Justice: “Attorney General James P. McGranery announced today that he had issued orders to the Immigration and Naturalization Service to hold for hearing Charles Chaplin when he seeks to re-enter this country.

“The hearing will determine whether he is admissible under the laws of the United States.”

An accompanying statement said that McGranery had taken the action under a provision permitting the barring of resident aliens on grounds of “morals, health or insanity, or for advocating Communism or associating with Communist or pro-Communist organizations.”

The reporters wanted a response from Chaplin.

Crocker sent a note to Chaplin, asking him to come immediately to Crocker’s cabin. Chaplin knew something was radically wrong as soon as he walked through the door—Crocker’s face had gone dead white.

Chaplin remembered that, as Crocker read the communiqué, “Every nerve in me tensed. Whether I re-entered that unhappy country or not was of little consequence to me. I would have liked to tell them the sooner I was rid of that hate-beleagured atmosphere the better, that I was fed up with America’s insults and moral pomposity, and that the whole subject was damned boring. But everything I possessed was in the States and I was terrified they might find a way of confiscating it. Now I could expect any unscrupulous action from them. So instead I came out with a… statement to the effect that I would return and answer the charges, and that my re-entry was not a ‘scrap of paper,’ but a document given to me in good faith by the United States government—blah, blah, blah.”

Chaplin’s statement: “Through the proper procedure I applied for a re-entry permit which I was given in good faith and which I accepted in good faith; therefore I assume that the United States Government will recognize its validity.”

By the time Crocker returned the first four calls, there were nine more waiting.

In chaotic circumstances, it was hard to get much information about what was being said in the newspapers back home. Chaplin and Crocker did find out that the Department of Justice refused to state specific grounds for revoking the reentry permit because, said one official, “It might prejudice our case.”

Despite being suddenly hurled into limbo, there wasn’t really much Chaplin could do other than continue with the routine of shipboard life for the rest of the crossing. Passengers saw him walking around the deck, reading, eating, and dancing with his wife after watching a movie.

The morning after the attorney general’s announcement, the Los Angeles Times page one banner headline read “U.S. BARS CHAPLIN: INQUIRY ORDERED.” The Chicago Tribune page one headline read “MOVE TO BAN CHAPLIN IN U.S.” with a heavily slanted accompanying story that said Chaplin “had scorned citizenship in this country,” that Congress had denounced him as “left wing and radical,” and that he had been declared the father of an illegitimate child. The fact that blood tests had proved Chaplin wasn’t the father was not mentioned.

As always, Chaplin’s automatic response to a crisis was to seek solace in work. At some point during the crossing, Chaplin took out a yellow legal pad and began outlining an idea for a film in his rapid, sprawling hand:

“An immigrant arrives in America and owing to the fact that he cannot be understood by the U.S. authorities, who try to discover him…”

He broke off. Flipping the page, he began again: “Arriving in America, an immigrant who speaks a strange language which the U.S. officials cannot understand, passes the immigration authorities, because of not being understood and, therefore, he does not come under the quota of any foreign nation.

“When he discovers that he is at last in America, he tries his best to get a job. He eventually gets a job. He eventually gets one as a [blank space] and gets into all sorts of complications because he does not understand the American language. Everybody tries to make him understand by pantomime and, of course, he only understands what he wants to understand.”

The idea harks back to the animating principle underlying Chaplin’s films as the Tramp: a well-meaning outsider at perpetual cross-purposes with his surroundings, doomed to isolation because of a basic imbalance in the relationship between an individual and conventional society.

When the Queen Elizabeth stopped in Cherbourg, reporters stampeded on board to talk to Chaplin, who tried to lower the temperature. He “was very surprised at the action, of course. I don’t know exactly in what circumstances it was taken.” He had, he said, “millions of friends” in America, and noted that “the government of the United States does not usually go back on such a thing as a re-entry permit. I am sure it is valid.” Furthermore, he said that the Immigration Department in New York had wished him bon voyage and “said they hoped I would soon return.”

And then he focused on what he believed to be the crux of the matter. “I am not political. I have never been political. I have no political convictions. I am an individualist and believe in liberty. That is as far as my political convictions go.” When a reporter asked him why he had never become an American citizen, he replied, “That has come in for a great deal of criticism. Super-patriotism leads to Hitler-ism. I assume that in a democracy one can have a private opinion. During the war I made several speeches sponsored by the government and several people took exception to what I said. I said nothing subversive in my opinion. I don’t want to create revolution. I just want to create a few more pictures.”

Over the next few days, the roster of American columnists who had been assaulting Chaplin in print for years weighed in all over again: “A menace to young girls.” (Westbrook Pegler). “Good riddance to bad rubbish.” (Hedda Hopper). “Maybe you’ll miss us, but I don’t think we’ll miss you.” (Florabel Muir).

Only Bosley Crowther of The New York Times and the columnist Dorothy Thompson stood up for Chaplin.

Crowther: “There is no way of knowing what evidence the Justice Department may have with which to challenge Mr. Chaplin when he seeks to re-enter the United States. But it would seem fairly reasonable to imagine that, if any evidence sufficiently strong to prove him a dangerous alien had been uncovered by now, it would already have been brought against him in a formal deportation suit. The basis for the Justice Department’s action remains to be disclosed.”

Thompson: “Judge him in the only way an artist can be judged—by his art—and he emerges as one of the most effective anti-Communists alive.”

Ed Sullivan, already fronting the television show that would banish memories of his reliably right-wing newspaper column, shot back at Crowther, scoffing at his assertion that Chaplin’s films had comforted and allayed the loneliness of first-generation Americans. Sullivan wrote that “what most Americans resented was non-citizen Chaplin’s loud interference in U.S. policy, plus his extension of the ‘little tramp’ role to his private life and dalliances. Crowther’s portrait of Chaplin as the right-hand man of U.S. naturalization officials is laughable.”

On September 21 the Los Angeles Times headlined a story “GOVERNMENT HINTS NEW FACTS IN CHAPLIN CASE.” Attorney General James McGranery took ten days to issue a statement elaborating on his reasons for the rescinding of the reentry permit. He asserted that Chaplin had “a leering, sneering attitude” toward America.

On October 3, McGranery held a press conference during which he referred to the banishment as a question of “morals” and called Chaplin a “menace to womanhood.” McGranery also said that the Department of Justice planned to deport one hundred “unsavory characters,” and included Chaplin in a roster that was otherwise made up entirely of mafiosi. In the same issue of Variety that reported McGranery’s remarks, Assistant Secretary of State Howland Sargeant contradicted the attorney general by saying that Chaplin “has every State Dept. paper he needs to get back into the country,” and that it was the Defense Department that believed him to be a security risk.

Confusion reigned.

Again, The New York Times stood up for Chaplin, this time in an editorial: “Those who have followed him through the years cannot easily regard him as a dangerous person. No political situation, no international menace, can destroy the fact that he is a great artist who has given infinite pleasure to many millions, not in one country, but in all countries. Unless there is far more evidence against him than is at the moment visible, the Department of State will not dignify itself or increase the national security if it sends him into exile.”

The back-and-forth continued for months, for years. And none of it made any difference.

Charlie Chaplin had been canceled.

NEITHER THE REPORTERS nor Chaplin were aware that, in the opinion of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, there would have been nothing the government could have done if Chaplin had demanded his reentry permit be honored. On September 29, ten days after the reentry permit was rescinded, in a meeting attended by INS deputy commissioner Raymond Farrell, it was noted that, “Mr. Farrell stated bluntly that at the present time INS does not have sufficient information to exclude Chaplin from the United States if he attempts to re-enter.”

They could, Farrell thought, make it difficult, perhaps even embarrassing, “but in the end, there is no doubt Chaplin would be admitted,” if only because he had never been found guilty of any crime. Furthermore, if the INS attempted to delay Chaplin’s reentry, the result “might well rock INS and the Department of Justice to its foundations.” A year or two later, the solicitor general of the Eisenhower administration, Simon Sobeloff, would say that the government had no grounds to ban Chaplin, let alone enforce a deportation.

Armed with this knowledge, the INS had to be able to counter with something devastating or risk looking foolish if Chaplin forced the issue. And so Lita Grey, Chaplin’s second wife, whose divorce complaint had charged him with adultery, as well as what the complaint characterized as degrading sexual acts, was questioned in an attempt to build a case against her ex-husband. On October 20, 1952, the FBI questioned Grey, but she steadfastly refused to help:

“They were desperately trying to build a case of moral turpitude because [my divorce complaint] contained intimate details of my sex life with him. I said, ‘I’m sorry gentlemen, but I am an adult now and I didn’t draw the complaint. It is true that most of the content is correct. However, the way it is presented, the words used, the description of sex, was all drawn up by my attorneys. I can’t cooperate with you. Besides, I have two wonderful children by Charlie and I don’t want to be responsible for keeping him out of this country.’?”

At the end of the interview with Grey, the FBI had no more on Chaplin than they had before September 1952. Had Chaplin wanted to come back to America, neither the FBI nor the INS could have stopped him.

But Chaplin would make no attempt to resume his life in America. Not then, not ever.

In a sense, it was all Sydney Chaplin’s fault. Charlie’s half-brother had a profound understanding of money and of comedy, but something of a blind spot about politics. On April 22, 1952, Sydney had written his brother suggesting he “take a run over to England for the opening [of Limelight]… in London & I don’t think you will have much trouble in obtaining a return permit & one that will be honered [sic] on your return.”

That same day, Sydney wrote a friend: “Regarding [rumors of] Charlie coming to live in Europe, I don’t place any value on that report. He has spent a lot of money having his house transformed to accommodate his larger family. However, I would not be surprised to see him make a trip to England for the showing of his picture and if he applies for a return permit, I think it will be granted & no obstacles in the way of his return. He has an American wife and 6 American children, two of which have fought for America in the last war. I think, except for the Catholic element, prejudice against Charlie has died down & from the government point, they know he has never been connected with any Communist organizations & for a period of 40 years he has been an asset & not a liability to America.”

Less than a month later, Chaplin began filing paperwork for the family jaunt through Europe. Sydney reported in a letter to his brother on May 2 that he had read in the papers that his namesake nephew, Charlie’s son Sydney, was going to play Shakespeare in Stratford. Sydney the elder thought Sydney the younger was wasting his time: “With his name and ability, he should now be earning big money either in the movies or on the TV. Look at some of the big salary boys, past & present.… Valentino was a dish washer, Clark Gable worked in a boiler factory, Cary Grant walked on stilts & gave away hand bills outside the New York Hippodrome. Harry Lauder came from the coal mines, the Chaplin Bros came from the gutter & Sir Henry Irving went broke playing Shakespeare. I am grateful that I learned to… do a cut-up fall.

“The years are fleeting &… as Doug Fairbanks used to say, ‘Life is a room with several doors & the problem is to know which door to open.’?”

BY THE TIME the Queen Elizabeth docked in London, Chaplin’s mood was markedly less conciliatory. The more he thought about it, the angrier he got. He vowed to return to America and fight the charges.

But reality forced him toward circumspection. Everything Chaplin possessed was in America. Not merely his home, his cash and securities, but the negatives of his films and his studio on La Brea Avenue. It wasn’t hard to imagine a scenario where he could become an elderly reconfiguration of the Tramp—stateless, impoverished. In the fall of 1952, it was once again clear that Charlie Chaplin’s life had an eerie way of prefiguring—not to mention explaining—his art. First psychologically, now literally.

So Chaplin once again opted for bland pronouncements: “I do not want to create any revolution. All I want to do is create a few more films. It might amuse people.”

A month after the revocation of the reentry permit, the FBI issued a massive internal report documenting more than thirty years of investigations focused on Chaplin, a copy of which was dispatched to the attorney general. The report revealed that, besides the FBI, Army and Navy Intelligence, the Internal Revenue Service, the Central Intelligence Agency, the Department of State, and the U.S. Postal Service had all been surveilling Chaplin at one time or another. In short, the entire security apparatus of the United States had descended upon a motion picture comedian.

The report’s ultimate verdict was that Chaplin was not and never had been a Communist, nor had he donated a dime to the cause. Nevertheless, the implicit conclusion was that the revocation of his reentry permit was justified for reasons evenly divided between sex and politics.

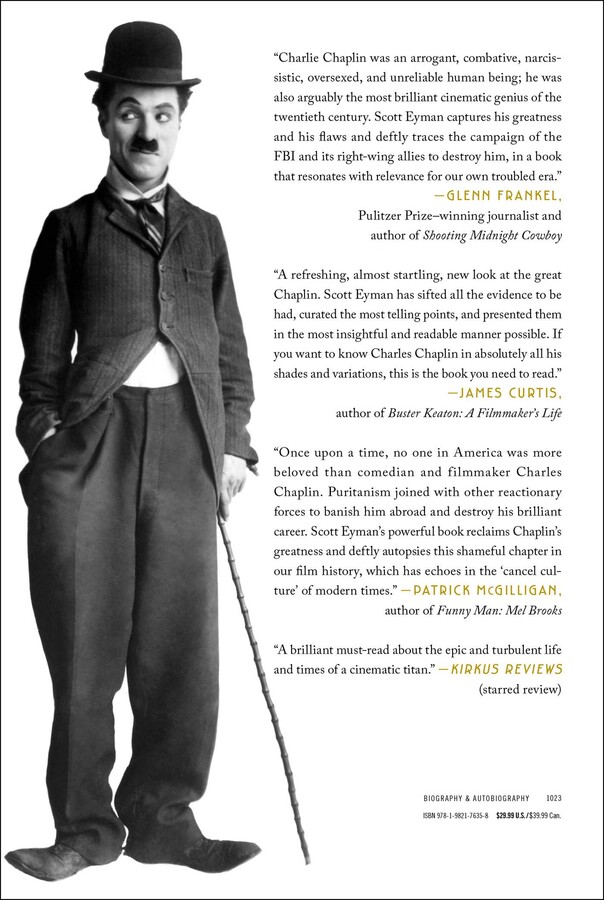

It was all very strange. For more than thirty years, Chaplin’s Tramp had navigated the perilous no-man’s-land situated between the way things are supposed to be and the way they actually are.

Early in his movie career, Chaplin’s social conscience had generally been limited to occasional jabs in otherwise apolitical contexts: the sharp, savage little moment when the immigrants are roped off like cattle just as the Statue of Liberty hoves into view in The Immigrant; the Bible Belt’s hypocrisy in The Pilgrim; the alcoholic millionaire in City Lights who sees the Tramp as his best friend when drunk and needy but doesn’t know him when sober—more or less a behavioral analogy for capitalism at its predatory worst.

America’s right wing sensed a heretic. The Pilgrim resulted in a formal protest from the South Carolina Ku Klux Klan, while the Evangelical Ministers’ Association in Atlanta called it “an insult to the Gospel.”

The overall tenor of Chaplin’s films began to shift with Modern Times in 1936, when Chaplin made rampant instability in a newly spawned age of anxiety wrought by a worldwide Depression the motivation for the entire film. The Tramp is forced into an incessant round-robin of survival strategies, all of which prove useless. Despite his focus on just getting by, the Tramp can’t avoid the stigma of Communism when he helpfully picks up a red flag that has fallen off a truck just as a mob of strikers comes around the corner. Result: arrest as a dangerous radical.

Chaplin’s disavowal of Communist politics could hardly be wittier, or more pointed.

Other than the huge success of The Great Dictator in 1940, the ensuing decade had been a largely dreadful period for Chaplin. The paternity suit confirmed suspicions that he was not merely politically subversive but sexually subversive as well. Despite the exculpatory results of the blood test, he was found guilty in court and, far more damagingly, in the court of public opinion. The speeches he had made on behalf of opening a second front to aid Russia, America’s ally at the time, had served as prima facie evidence of Communist sympathies. “I don’t want the old rugged individualism,” he had proclaimed. “Rugged for a few, ragged for many.”

In 1948, the FBI began perusing reports gathered over the previous twenty-six years to “determine whether or not CHAPLIN was or is engaged in Soviet espionage activities”—an investigation focused on the intrinsically absurd idea that a multimillionaire was plotting to overthrow capitalism.

James McGranery’s action was the culmination of years of a concerted campaign targeting the private sexual behavior and public political sympathies of the most dangerous brand of dissident—a beloved popular artist. The result was excision from the body politic as if he was a collection of malignant cells.

The action would disrupt both Chaplin’s career and recently stabilized private life—this decade also brought the emotional security he had sought his entire life in his 1943 marriage to Oona O’Neill, which lasted the rest of his life and produced eight children.

THIS BOOK IS a social, political, and cultural history of a crucial period in the life of a seminal twentieth-century figure—the original independent filmmaker who gradually fell into mortal combat with his adopted country precisely because of the beliefs that formed the core of his personality and films.

At a time when political and cultural paranoia converged, the FBI did not restrict itself to the collection of facts, but actively proselytized for the image of Chaplin as subversive, freely disseminating a steady stream of largely unsubstantiated disinformation to Chaplin’s political adversaries. Chaplin became the most prominent victim of what amounted to a cultural cold war—a place where art always loses.

America lost a lot in this period. So did Chaplin. A King in New York and A Countess from Hong Kong, the two films he made after his forced exile, are a precipitous decline from Monsieur Verdoux and Limelight.

This is the story of one of the earliest junctions between show business and politics, of how a theoretically liberal Democratic administration capitulated to a Red Scare made up of what Dean Acheson called “the primitives,” a phrase that in its aloof condescension predates Hillary Clinton’s “basket of deplorables.”

In the twenty-first century, Charlie Chaplin remains popular but is no longer fashionable. Most modern critics prefer the apolitical, slightly autistic comic character of Buster Keaton, an artist with whom Chaplin had little in common beyond their mutual profession.

Keaton is an abstract artist with a strong bent toward the surreal, not to mention the depressive. His character relates more to things than people—he’s focused on getting his cow back, or his locomotive. People are an afterthought.

Chaplin is a figurative artist and a romantic, and his area of interest is always people and their place in the world—Modern Times, The Great Dictator, and Monsieur Verdoux all examine societies tightly organized against the powerless, while Limelight focuses on the ostracizing effects of age and failure.

In her “Notes on Camp,” Susan Sontag posited that “the two pioneering forces of modern sensibility are Jewish moral seriousness and homosexual aestheticism and irony.” Chaplin wasn’t Jewish but he might as well have been, for he was morally serious long before the Holocaust, even as his cultural and political enemies insisted on defining morality as strictly relating to sex.

This book focuses on the planned ideological strikes that banished Chaplin from his adopted country while he was engaged in making the most controversial films of his life—a story that eerily foretells the homicidal cultural and political life of the twenty-first century.

It is also about an indomitable, compulsively creative man struggling to sustain his voice in an art form evolving in ways that didn’t play to his strengths. Finally, it is about how Charlie Chaplin lost his audience, then gradually found it again.

It’s time to see Charlie clear.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (November 23, 2023)

- Length: 432 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982176358

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"Better than any other biographer that has gone before, Eyman gets underneath Chaplin and explains that complex personality."

– San Francisco Chronicle

"Fun to read. . . . Eyman is completely sympathetic to Chaplin, and he makes the case that we should be, too."

– Louis Menand, The New Yorker

"Seventy years later, Chaplin’s exile seems even more shocking than when it occurred. . . . In Charlie Chaplin vs. America the film historian Scott Eyman. . . . Makes clear how much the government’s crusade cost us all."

– Jeremy McCarter, The Wall Street Journal

"one of the finest surveys of the man and the artist ever written. . . . A gem of a book."

– Leonard Maltin

"A brilliant must-read about the epic and turbulent life and times of a cinematic titan."

– Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

"Eyman brings his fine writing and rigorous research to the later years of Charlie Chaplin’s remarkable career. . . . An essential addition to every film history collection."

– Booklist

"Distinguished research, featuring the over 1,900-page FBI report, media accounts, and interviews with family members, coworkers, and historians, propels this excellent biography that captures Chaplin, both the person and his work."

– Library Journal (starred review)

"Charlie Chaplin was an arrogant, combative, narcissistic, over-sexed and unreliable human being; he was also arguably the most brilliant cinematic genius of the 20th century. Scott Eyman captures his greatness and his flaws, and deftly traces the campaign of the FBI and its right-wing allies to destroy him, in a book that resonates with relevance for our own troubled era."

– Glenn Frankel, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of Shooting Midnight Cowboy

"Once upon a time, no one in America was more beloved than comedian and filmmaker Charles Chaplin. Puritanism joined with other reactionary forces to banish him abroad and destroy his brilliant career. Scott Eyman's powerful book reclaims Chaplin's greatness and deftly autopsies this shameful chapter in our film history, which has echoes in the 'cancel culture' of modern times."

– Patrick McGilligan, author of Woody Allen: A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham

"A refreshing, almost startling, new look at the great Chaplin. Scott Eyman has sifted all the evidence to be had, curated the most telling points, and presented them in the most insightful and readable manner possible. If you want to know Charles Chaplin in absolutely all his shades and variations, this is the book you need to read."

– James Curtis, author of Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker's Life

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Charlie Chaplin vs. America Hardcover 9781982176358

- Author Photo (jpg): Scott Eyman Photograph by Greg Lovett(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit