Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

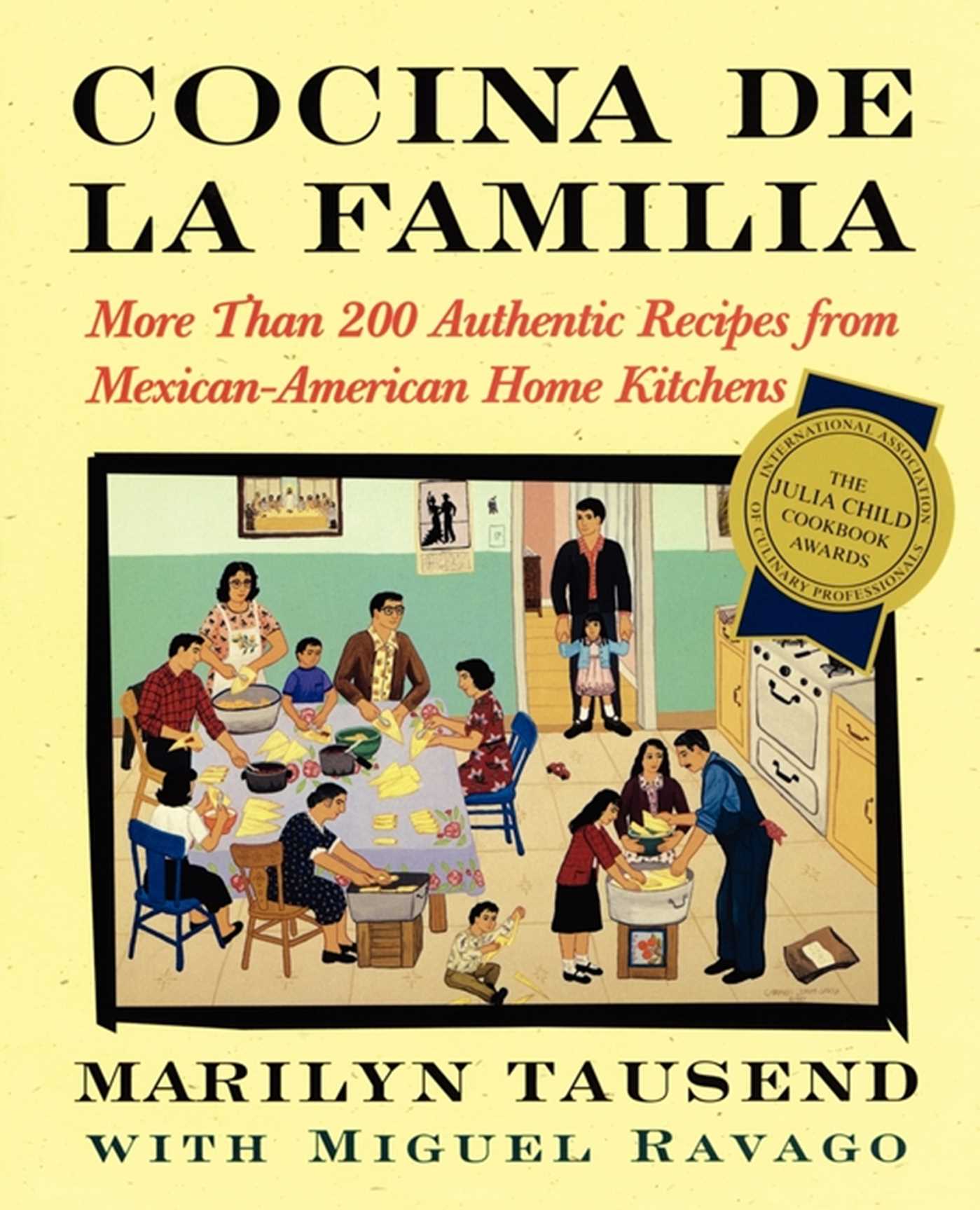

Cocina De La Familia

More Than 200 Authentic Recipes from Mexican-American Home Kitchens

Table of Contents

About The Book

For three years, Marilyn Tausend traveled across the United States and Mexico, talking to hundreds of Mexican and Mexican-American cooks. With the help of chef Miguel Ravago, Tausend tells the tale of these cooks, all of whom have adapted the family dishes and traditions they remember to accommodate a life considerably different from the lives of their parents and grandparents.

In these pages you will find the real food eaten every day by Mexican-American families, whether they live in cities such as Los Angeles, the border towns of Texas, the farming communities of the Pacific Northwest, or the isolated villages of New Mexico. An Oregonian from Morelos, Mexico, balances sweet, earthy chiles with tart tomatillos for a tangy green salsa that is a perfect topping for Chipotle Crab Enchiladas or Huevos Rancheros. A Chicago woman from Guanajuato pairs light, spicy Chicken and Garbanzo Soup with quesadillas for a simple supper. A Los Angeles cook serves a dish of Chicken with Spicy Prune Sauce, the fire of the chiles tamed by Coca-Cola, and in Illinois a woman adds chocolate to the classic Mexican rice pudding.

Now you can re-create the vibrant flavors and rustic textures of this remarkable cuisine in your own kitchen. Most of the recipes are quite simple, and the more complex dishes, like moles and tamales, can be made in stages. So take a savory expedition across borders and generations, and celebrate the spirit and flavor of the Mexican-American table with your own family.

Excerpt

For much of the past three years I have traveled back and forth across the United States talking to hundreds of Mexican and Mexican-American cooks, hearing their stories, and collecting their recipes. Seldom were the ingredients or instructions written down, but I learned from watching, listening, and talking. Cocina de la Familia is the tale of these many cooks -- all of whom have adapted the family dishes and traditions they remember from their past to accommodate a life considerably different from the lives of their parents and grandparents.

This is a transition that deserves to be understood. As society changes, our eating habits change. Most home cooks, whether in Mexico or anywhere else in the world, were women who did it out of necessity and not because of a creative urge. What they cooked came less from individual fancy than from knowledge passed on from generation to generation.

Today's Mexican cooks may use oil instead of lard, canned instead of fresh tomatoes, or a food processor instead of grinding on a slab of volcanic rock, but food is still the strand that ties them to their past. María, who lives and works in Sacramento, California, but whose family is from a small village near Guadalajara, says it best: "In our culture, food is much more than just nourishment. It connects us. It isn't just served at a celebration, it is a celebration."

It is this celebration of the food -- the spirit of the country itself -- that I have tried to focus on in these contemporary recipes from Mexican-American kitchens. I think it is important to stress that I use the word "contemporary" to mean real food eaten every day by Mexican-American families, whether they live in cities such as Los Angeles or Chicago, the border towns of Texas or Arizona, farming communities in the Pacific Northwest, or the isolated villages of New Mexico and southern Colorado. This is food that has its roots in the prehistoric soil of Mexico but has branched out, survived, and flourished in this modern world.

I am not Mexican by birth, heritage, or citizenship. But my relationship to the food of Mexico spans more than half a century. My father was what is called a carlot produce distributor, which means that he bought produce such as onions, potatoes, and citrus fruits from the fields and orchards, and sold them by the railroad car to wholesale buyers in Chicago and New York. By necessity, I grew up following the rhythmic cycle of the growing season throughout southern Texas, the Central Valley of California, and southern Idaho. I slept at night in hotels and motor courts, and I learned about food by sharing meals with the Mexican and Mexican-American migrant field-workers.

I must have aroused the passionate maternal nature of the Mexican women as I trailed my father around in the fields. No matter that they were living out of cars and cooking over a butane burner, they showed their compassion in the way they knew best: by having me share the flavors and textures of their foods -- and lives. When I was about eleven, I think, I worked the crops with my Mexican-American friends. They showed me the fastest way to top onions for seed, to pick peaches from the top of the tree without falling off the ladder, and to weed corn without disturbing the roots. Then they shared with me their midday meal. I remember thick tortillas wrapped around a chile -- pungent stew of meat, all tied together in a bandanna and left in the shade until time to eat. My hands were small, and it took many tries before I could tip the rolled tortillas just right, curling my fingers around the far end so that none of the sauce squished out and ran down my chin.

I remember one large family that seemed to be all male, every age and every size. They often brought a large red coffee can filled with slightly warm but still crispy potato cakes made with lots of springy cheese. We would pile them with a salsa made of freshly picked tomatoes so ripe that they popped open when pricked with a thumbnail. The tomatoes, a milky white onion, and very tiny, very hostile chiles were all chopped together on the lid of the can with a sharp, shiny knife. We'd eat sitting beside the irrigation ditch, kicking our feet in the slow-moving water and splashing ourselves to cool off.

I can still recall a young girl, about my age, making up a bed of old blankets in the backseat of a beat-up old Ford, then laying down a tired toddler and gently fanning him to sleep with corn leaves. One full-moon-faced woman had a new baby with her every year -- always wrapped tightly in a dark-colored rebozo while she bent over weeding up and down the furrows. This was my first conscious sight of a nursing mother, milk dribbling out around the baby's mouth and sweat running down the woman's bare neck and chest. I admired the men with their muscular arms and would know envy when one would stop by his wife and casually stroke her neck. I watched it all, absorbing the love I felt around me. It was then, too, that I began to equate Mexican food with that unusual balance of contentment and excitement.

Decades later, after raising my own family in largely Scandinavian and Yugoslavian communities, I set out to rediscover these foods of my past. They certainly weren't being served in the Mexican chain restaurants that dotted the strip malls near where we lived. I began to wonder if they were anywhere but in my memory.

The logical place to search seemed to be in Mexico itself. And, like Columbus, I found a culinary world that I didn't know existed -- one more vast and varied than I had imagined. The more my husband, Fredric, and I traveled and tasted, the happier I became.

Early on, I was lucky enough to become friends with Diana Kennedy, who is perhaps the greatest living expert on the traditional cooking of Mexico. With her guidance I began to recognize the ingredients and cooking techniques common throughout the country and, just as important, to search out and understand the divergent characteristics of regional food. I was intrigued by all of the dishes but always wondered where I could find similar ones in the United States if I didn't prepare them myself.

The answer came while I was in Oaxaca sharing a late evening meal with Emilia Arroya de Cabrera, a friend of several years. Her dining room table held a bowl -- the same sun-glazed earth tones as the parched hillsides -- filled with a clear broth. Tendrils from young squash plants were twisted among the submerged hunks of pale yellow corn, the kernels still attached and encircling the cob. A platter held curds of soft scrambled eggs gashed by vivid red streaks of colorin blossoms. There were two salsas, one red and one green, and a basket of corn tortillas, heat-freckled on the comal.

Emilia's mother had cooked this satisfying supper just as she prepared most of the family food. Though a simple meal, the visual contrasts of color and texture, the harmonizing tastes of fresh seasonal ingredients, and the aroma that filled the room made it very special.

After supper I sat on the couch with Aurora, one of Emilia's daughters, who had recently married a Texan. When I casually asked what she cooked in her new home, she replied, "The dishes I learned from my grandmother, of course."

"The dishes I learned from my grandmother" became the starting place for my new culinary search -- one that would lead across the United States and into the kitchens of many Mexican Americans like Aurora. I set out to discover how 13 million United States citizens of Mexican heritage -- those of first, second, third, and even eighth generations -- were creating their traditional dishes.

I found that Mexico's indigenous ingredients -- primarily corn, beans, chile, and tomatoes -- continue to be the foundation of all Mexican cooking. Squash, turkey, and avocado are as important now as they were in the days when Cortés came ashore in Mexico. Equally important are rice and wheat, as well as the many types of citrus fruits and all the different livestock and their products, incorporated into the cuisine by the Spanish. In the face of both the opportunities and the restraints of today's world, what has changed is the use of time-saving equipment and products, the introduction of many other ethnic influences, and an emphasis on healthier eating.

This was a way of cooking that I wanted to learn more about and then to share. I asked these cooks for their hoarded taste memories. I ate and I cooked with them, observing how they modified the traditional foods of remembrance and wove them into the fabric of their everyday lives.

In Los Angeles I discovered an unusual chicken dish with a prune and raisin sauce; its flavor was heightened with chipotle chile and soothed by Coca-Cola. From Miami, by way of Guanajuato, came traditional rustic enchiladas together with chile -- sauced chunks of carrots and potatoes. But in Detroit a more diet-conscious cook substituted bean curd, spinach, and yogurt. In Illinois, a cook added chocolate to the classic Mexican rice pudding, and mustard enhanced a shredded beef salad in El Paso. The list goes on and on.

Most of the recipes are quite simple, but even the more complex dishes -- moles or tamales -- can be made in stages. The ingredients should be easy to find unless it is an out-of-season product. In that case, a substitute will be listed.

Throughout all my journeys I discovered one consistent theme: During the many years as Mexicans became Mexican Americans, whether by annexation or by immigration, and in times of discrimination and estrangement, they kept their past alive in their homes through the stories they told and the food they cooked. Everywhere I went I saw how for most Mexican Americans the family has played a major role as a defense against an often indifferent, even hostile, society, and the family is extended to include grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins related by either blood or marriage. It is through this larger family that the Mexican customs and culinary heritage are being preserved.

Many experts say that home cooking is becoming obsolete. More of us have the means to eat out often or, if in a hurry, to buy already prepared foods, but then we find that these mass-produced meals rarely satisfy: They lack heart. The conditions that created the recipes in this book cannot be duplicated, but those who use the recipes will learn where the dishes originated, the history and tradition behind them, who makes and eats them now, and how to re-create the dishes in their own kitchens to enjoy with their own families.

Copyright © 1997 by Marilyn Tausend

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria Books (December 17, 1999)

- Length: 416 pages

- ISBN13: 9781439137208

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

Rick Bayless chef/owner, Frontera Grill and Topolobampo, and coauthor of Rick Bayless's Mexican Kitchen and Authentic Mexican Marilyn Tausend's Cocina de la Familia leads us on a savory Mexican expedition across borders and generations, from mercados to supermarkets -- yet always winding up at the coziness of a family table, where food tastes best. She illuminates how the loving act of cooking for family and friends is a vital way to keep alive memory and heritage.

amazon.com.review Forget about the food you eat in what pass for Mexican restaurants in America; cleanse your palate, then come to this book.

Kathleen Purvis food editor, The Charlotte Observer Well, hallelujah. After endless books celebrating the cooking of France's Provence and Italy's Tuscany, perhaps we're finally coming to appreciate what we have right here. Tausend's writing is eloquent as she captures the voices and stories of people who are too often ignored in the tapestry of American cooking. Bravo for that.

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Cocina De La Familia eBook 9781439137208