Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

“Erica Garza has written a riveting, can’t-look-away memoir of a life lived hardcore…In an era when predatory male sexual behavior has finally become a topic of urgent national discourse…Getting Off makes for a wild, timely read” (Elle).

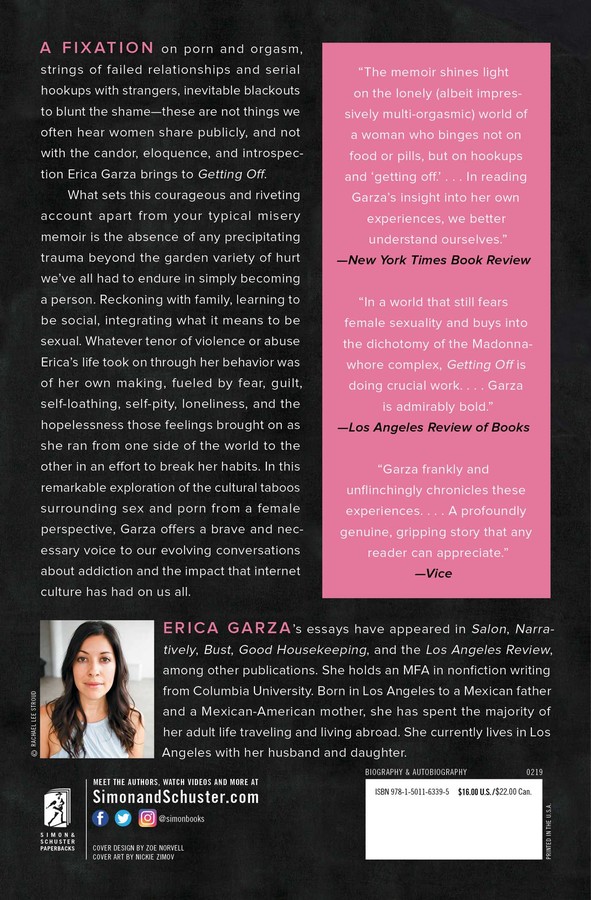

A fixation on porn and orgasm, strings of failed relationships and serial hook-ups with strangers, inevitable blackouts to blunt the shame—these are not things we often hear women share publicly, and not with the candor, eloquence, and introspection Erica Garza brings to Getting Off.

What sets this courageous and riveting account apart from your typical misery memoir is the absence of any precipitating trauma beyond the garden variety of hurt we’ve all had to endure in simply becoming a person—reckoning with family, learning to be social, integrating what it means to be sexual. Whatever tenor of violence or abuse Erica’s life took on through her behavior was of her own making, fueled by fear, guilt, self-loathing, self-pity, loneliness, and the hopelessness those feelings brought on as she runs from one side of the world to the other in an effort to break her habits—from East Los Angeles to Hawaii and Southeast Asia, through the brothels of Bangkok and the yoga studios of Bali to disappointing stabs at therapy and twelve-steps back home. In these remarkable pages, Garza draws an evocative, studied portrait of the anxiety that fuels her obsessions, as well as the exhilaration and hope she begins to feel when she suspects she might be free of them.

Getting Off offers a brave and necessary voice to our evolving conversations about addiction and the impact that internet culture has had on us all—“a profoundly genuine, gripping story that any reader can appreciate” (Vice). “In reading Garza’s insight into her own experiences, we better understand ourselves” (The New York Times Book Review).

A fixation on porn and orgasm, strings of failed relationships and serial hook-ups with strangers, inevitable blackouts to blunt the shame—these are not things we often hear women share publicly, and not with the candor, eloquence, and introspection Erica Garza brings to Getting Off.

What sets this courageous and riveting account apart from your typical misery memoir is the absence of any precipitating trauma beyond the garden variety of hurt we’ve all had to endure in simply becoming a person—reckoning with family, learning to be social, integrating what it means to be sexual. Whatever tenor of violence or abuse Erica’s life took on through her behavior was of her own making, fueled by fear, guilt, self-loathing, self-pity, loneliness, and the hopelessness those feelings brought on as she runs from one side of the world to the other in an effort to break her habits—from East Los Angeles to Hawaii and Southeast Asia, through the brothels of Bangkok and the yoga studios of Bali to disappointing stabs at therapy and twelve-steps back home. In these remarkable pages, Garza draws an evocative, studied portrait of the anxiety that fuels her obsessions, as well as the exhilaration and hope she begins to feel when she suspects she might be free of them.

Getting Off offers a brave and necessary voice to our evolving conversations about addiction and the impact that internet culture has had on us all—“a profoundly genuine, gripping story that any reader can appreciate” (Vice). “In reading Garza’s insight into her own experiences, we better understand ourselves” (The New York Times Book Review).

Excerpt

Getting Off one THE GOOD GIRL

I grew up in the early eighties in Montebello, California, Southeast LA, where teenage pregnancy was on the rise and every Mexican restaurant claimed to have the best tacos north of the border. Living rooms were adorned with framed pictures of Jesus or the Virgin, and everyone believed in heaven and hell—not as abstract ideas, but as very real places. It was the kind of place where you could pick up your holy candles with your milk and bread at the local supermarket and you always knew someone celebrating a baptism or First Communion soon—giant events requiring ornate outfits and tres leches cake and a sense of relief on everyone’s part that things were good with God, no one was going to hell just yet.

I rarely met anyone who wasn’t Catholic. When it did happen, it was whispered about. Did you know Mrs. Gonzalez is a Jehovah’s Witness? Isn’t that weird? If you weren’t Catholic, to whom would you turn for help? No priest? No Bible? It was unclear how a person could distinguish right from wrong without the Commandments. And I didn’t even want to think of what happened to them after death. I imagined babies dying before they were baptized and shuddered at their unfortunate fates.

I often tell people now that I come from LA, or sometimes East LA if I want to hint at my Latino roots. LA is Hollywood glamour, money, and prestige; East LA screams danger, gangs, and irrefutable street cred. In truth, my life had neither. Montebello and all Southeast LA, home to cities like Bell Gardens, Pico Rivera, and Norwalk, were small, mediocre, boring.

My dad, a mortgage broker, helped low-income Mexicans buy first homes, while my mom, a housewife, made sure our home was intact. They balanced their checkbooks, and we bought clothes at Ross, and the only place we traveled to outside of the country was Tijuana, which my mom often said “didn’t count” since it was only two hours south. My brother, Gabe, and I ran through sprinklers in the summer or laid down giant plastic trash bags for slipping and sliding. Katie Wilkins, a white girl, lived next door to us, which was rare in a predominately Mexican neighborhood, and I’d often peer at the swimming pool in her backyard from my bedroom window with envy. Mediocrity, which I felt was directly connected to my heritage, was my first source of shame.

But, in retrospect, we seem more privileged than I realized. I vacationed in Hawaii and Walt Disney World. I attended private Catholic school, from kindergarten through high school. My dad owned and ran a mortgage company for nearly twenty years until he sold it for a large sum and bought himself his dream car, a flashy Corvette that looked like the Batmobile, and a vacation condo in Maui. And by the time I entered high school we had moved into a house with a pool. I never knew what it was to go to bed hungry or face eviction, but shame has a way of being irrational. I looked at our life and I wanted more.

I simply couldn’t understand why my parents would want to live in such a boring place. There seemed to be nothing but strip malls and taco stands, nail salons and bail bonds. But to them, and to other Mexicans, Montebello was a big deal. In the late sixties and early seventies, when they were growing up, Montebello was nicknamed “the Mexican Beverly Hills.” Housing prices were more expensive and the streets were safer than those in nearby East LA, where my mom spent her formative years. Tomas Benitez, the Chicano author and activist, said in an interview with LA’s KCET, “Montebello was mythic when I was growing up in the 1970s. It was the place where middle-class Mexican-Americans lived and came from. It had that quality, if you could get out of East LA, Montebello was Nirvana, the promised land and Beverly Hills East all rolled into one location.”

For my dad, who was born under modest circumstances in Mexico City and whose own father was an orphan, to be able to live in the Mexican Beverly Hills as an adult was a big step up. He played golf at the city’s country club every weekend and served as an important figure in the city’s Rotary International organization. We often ran into people who knew and respected him wherever we went—restaurants, the bank, the supermarket—and they’d shake his hand with sincerity, reassuring me and my older brother, “Your dad’s a good man,” in case we ever doubted it.

My mom, on the other hand, was less interested in the community. She often complained about the city’s lack of good stores and its seemingly endless pavement. Sometimes she even complained about its propensity for attracting wetbacks, always laughing after this admittance, especially if my dad was around, before she’d lovingly touch his arm and coo, “Aww, I married a wetback.”

That term wetback, coined from those Mexicans who illegally crossed the Rio Grande to get to America, was not an accurate description of my dad, who had crossed the border legally and traveled by road, not river. But that didn’t stop my mom from muttering the word whenever she was feeling playful, or worse, when she was feeling wicked. Even though she has Mexican roots herself, I always thought that her teasing meant she considered natural-born citizens superior to those who had been naturalized. She would have likely picked this idea up from her own dad, a WWII veteran whose own parents were immigrants, and whose dark skin made him feel inferior in a country that was even harsher toward Mexicans than it is today.

The problem, for me, was that my neighborhood and my place inside it didn’t resemble my preconceived notions of power. It didn’t matter that my classmates at school shared the same Spanish-sounding last names and most of their grandmas didn’t speak English either. I took note of the Mexican guy selling oranges on the corner, and the busboy picking up our dishes topped with messes of ketchup and crumbs, and I thought, No, that’s not me. I even convinced myself now and again that I was superior to those kinds of Mexicans because my parents hadn’t taught me Spanish. We were outgrowing our Mexican-ness, I thought to myself. Pretty soon it would be gone completely, forgotten like a dream.

My feelings of superiority never lasted long. I knew my classmates and I were part of a minority, and I didn’t like the sound of that word, sitting heavy in my mouth and mind. I wanted to be like the blond-haired, blue-eyed Tanner girls on Full House. I wanted the calm, sensible family talks like the Seavers had on Growing Pains. I wanted a family tree that stretched back to Europe. Maybe England or Ireland, France even. But not Spain.

I got hooked on TV at a young age, marking the beginning of my intense bond with screens, and TV served as a window into the exciting world out there. I became obsessed with the families and neighborhoods I saw that were different from my own—which is to say, white. There was no George Lopez on TV then, no Sofia Vergara or America Ferrera. And I deemed the world “out there,” on the TV screen and in the heart of glittering Hollywood, to be far superior to the Mexican Beverly Hills with its baldheaded gangsters, its teenage mothers, and its paleta men making their living selling sweet treats to kids on clean, suburban pavement.

Unlike my dad, who seemed perfectly content with his roots and his chosen city of Montebello, I leaned more toward my mom’s chronic dissatisfaction and her fondness for escape. Like me, my mom also found herself captivated by screens. She loved foreign films—Cinema Paradiso, Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, Shirley Valentine—and I’d cuddle up with her on the couch for countless cinematic escapes, placing myself in the films and imagining the adventures waiting for me in adulthood.

Sometimes I would imagine taking trips with my mom. It’s not that I didn’t love my dad or that I wanted her to leave him forever, but maybe a few months? A year? I picked up on the tension that arose between my parents if my dad was working late again or on another client call. He usually returned from the office when we were already tucked into bed and was gone in the morning before we’d had a chance to get up, always trying to get ahead at the expense of my mom’s growing resentment. My brother and I got used to having my dad around only on the weekends. But even then there were always more phone calls, more stacked files in front of him, and my mom found this difficult to accept, alternating between giving him the silent treatment and erupting in angry outbursts, depending on her mood.

My mom’s moodiness became more pronounced as I grew older. Some days she’d park herself in front of the TV, bored eyes glazed over by some daytime talk show or murder mystery. Other days she’d take me to the mall to try on clothes and feast at the food court, deep-fried corn dogs with mustard and curly french fries. And yet other days she’d be annoyed by everything—the dirty dishes, the piles of laundry, her lazy children—and I’d think to myself, She just needs a break. If we go away for a little while, she’ll feel better.

When my mom was upset, I sought solace in playing video games with Gabe, who was three years my senior. We spent hours toting machine guns in Contra, gobbling up mushrooms in Super Mario Bros., and scouring mythic lands for Zelda. I became obsessed with trying to beat him, frantically studying video-game magazines to learn the latest cheats, training myself not to blink, lest I miss a bullet or fireball and lose. When I wasn’t playing, I was thinking of playing. When I was playing, I was thinking of what I’d play next.4

When we weren’t saving princesses in front of the TV screen, Gabe and I were putting ourselves on the screen, acting out short films he wrote and directed—he’d decided early on he was going to be a famous filmmaker when he grew up. Gabe’s gift for screenwriting and his skillfulness with my parents’ camcorder earned him a lot of admiration. Family parties invariably involved the screening of a movie Gabe was making with my cousins and me as actors, typically toward the end of the night when our parents were tipsy and jovial.

I came to resent what I saw as Gabe’s creative genius, even when my mom encouraged my rising interest in writing, buying me books and journals that I filled mostly with complaints about my brother intermingled with praise for all the boys I had crushes on at school. And whenever she caught me complaining about something being unfair, she’d murmur, smiling, “All the best writers had rough childhoods.”

When Gabe didn’t want to play with me, I’d terrorize him with kicks and shoves until he’d eventually shove me back, at which point I’d run crying to my mom in hopes he’d get punished. When she’d reprimand him, her long, curly hair shaking wildly around her face, I’d stand behind her, laughing and waving my hands at him, thinking, I win! She loves me more than you!

Despite my mom and dad’s persistent praise of Gabe, I clung desperately to the idea that my mom loved me more. We were girls, after all, and this meant something. That’s why she let me skip school and lie lazily in bed with her some days, watching movies and eating popcorn, saying, Don’t tell Dad I let you skip again. I loved keeping secrets with her.

One night, when I was ten years old, my parents told us kids we’d have dinner in our fancy dining room. I was confused. My dad rarely made it to dinner. I thought the dining room was reserved for Thanksgiving and Christmas only. And were those candles?

I had heard the word divorce slither out of my mom’s mouth on a few occasions when she was gossiping about my uncle’s ex-wife, or when she was talking about certain kids’ parents at school, and I wondered to myself if this is what was happening. Were my parents treating my brother and me to one final moment of togetherness before my dad packed up his suitcase? Would we be divided between them? Clearly I’d stay with my mom. And then, immediately after, I wonder where we’ll travel to first.

“Your dad and I have some big news,” my mom said, an excited smile on her face. A glass tumbler sat in her hand, filled to the brim with Pepsi and ice cubes, and she took gentle sips, letting suspense build around the table.

I looked at my dad, and he was smiling too.

“What is it?” Gabe said.

I kept my mouth shut, feeling excited yet guilty. Had I actually willed this into happening? Did all my imaginings of traveling the world with my mom come to fruition simply because I thought them? I considered the gravity of what this meant, that I had the power to destroy my parents’ marriage with my mind. I pictured myself as some kind of witch, a source of power and wickedness.

“You want to tell them?” my mom asked my dad.

“OK,” he said, and I held my breath.

“Your mom’s going to have a baby!”

My mom exploded in giggles, the ice cubes in her Pepsi clanking against the glass while she stood up to give me and my brother kisses and hugs. But when she pulled me close to her, my face pressed against her cotton blouse, I burst into tears.

“Oh, baby, why are you crying? What’s wrong?” She tried to pull away to look at my face, but I clung tight, digging my nails into her arm, refusing to let go. “Erica, what’s wrong?”

I heard my brother laugh, confused by my reaction. And I felt my dad come over beside us and put his warm hand on my quivering head. But I didn’t know how to explain the panic I felt at being cast aside, overshadowed by Gabe’s talent and the importance of a brand-new baby, and so I lied when they asked again, “Erica, why are you crying?”

Finally, I answered, “Because I’m happy.”

I can remember, vividly, the sexual fantasies that bubbled in my brain, seemingly out of nowhere, during my mom’s pregnancy. To distract myself from thinking about my new sibling, I turned my attention to other, more captivating places and daydreamed constantly. There’s nothing like the bulging belly and emotional intensity of a pregnant woman to inspire curiosity about how it all works—babies, sex, the origin of life.

All I had ever heard about sex from my parents came from my mom when, passing the local high school, she pointed out a few pregnant girls who couldn’t have been older than sixteen and said, “Don’t ever let that happen to you”—and then, pointing to my crotch—“don’t let anyone ever touch you down there.”

My mom and dad both seemed uncomfortable when it came to addressing sex, and they were equally as aggressive about hiding it from me.5 When things got hot and heavy in whatever movie we were watching, the response was immediate: “Close your eyes until we say,” and I complied, listening to the indistinct sounds of what I was not allowed to see until it was all over.

I can understand my parents’ reluctance at not wanting to talk about sex with me at ten years old, but “the talk” never came.6 Sex was something dirty and sinful, something to blush about, something to hide. These were obviously inherited ideas. My grandparents on both sides had the same reactions when a love scene unexpectedly danced across the TV screen: a shriek of discomfort followed by covered eyes and the demand that somebody change the damn channel. Whether it was a Latino thing7 or a Catholic thing, I couldn’t be sure. Even my teachers laughed uncomfortably and avoided eye contact when they explained that sex was something that happened “between two married people who loved each other,” for one reason alone: procreation.

Though I had limited knowledge of how sex worked, I began gradually piecing it together when my parents weren’t around. I’d been making lists of boys I wanted to kiss in my journal for a few years, but the lists became longer during my mom’s pregnancy, and sometimes even included rudimentary drawings of body atop body next to the lists. There seemed to be no one I didn’t find attractive in my fifth-grade class; I wanted all the boys—and some of the girls too—and even our teacher, Mr. Rivera.

In class, I’d stare at Mr. Rivera’s crotch, trying to imagine what he looked like under his clothes. I stared at my female teachers’ breasts and long legs. I stared at my classmates’ bodies with such unquenchable curiosity and thirst, but I had no idea what to do with this desire except to try and ignore it, though the bubbling in my brain proved difficult to control. And since no other girls were talking about this kind of thing, and I wanted desperately to be a good Catholic girl, I figured something terrible was happening to me.

Though I had attended Catholic school since kindergarten and weekly Mass was part of the curriculum, I didn’t pray much. I made the sign of the cross with holy water, I closed my eyes and folded my hands so I looked like I was deep in prayer, and I confessed to the priest when required (always the same sins: Bless me, Father, for I have sinned. I fought with my brother and I said bad words), but these rarely felt like real acts of faith. They were obligations. My parents didn’t pray much either. Not publicly, at least. For a short time, we attended Sunday Mass a few times a month, but then we turned into what my mom called “part-time Catholics,” attending only during the holiest events, like Christmas and Easter. Pretty soon, we stopped going completely, so Mass felt like another school period. Despite this lack of practice, when I found out my mom and dad were having the baby, I started praying for one thing daily: Please let the baby be a boy.

I had to maintain my specialness somehow, and being the only girl seemed the best route. I was already used to being the only girl, not only of my immediate family but also among all my cousins. When Gabe wrote a new screenplay, I naturally got all the female parts and I was the sole recipient of the kind of oohs and aahs that come with being the only kid wearing a pretty dress or sporting a new perm or having sparkly nails or whatever other girlie thing my mom bought for me that my aunts loved. I had a few female younger cousins, but they were too little to prove what good and pretty and polite little girls they were. I had that covered.

I wrote down my favorite little-brother names in my journal—Freddy or Jason, because I loved horror movies—and I knelt at the foot of my bed in tireless devotion to God, whom I thought of as a magic genie then, thinking, I will be a good girl forever if you grant me this one wish.

But God showed me what he thought of my wishes when my mom brought home the shadowy sonogram print of her new baby girl.

“Look at your little sister, Erica,” my mom said, handing over the picture. “Her name is Ashley.”

I held the print in my hand, terror rising in my throat as I tried to make sense of the black-and-white blob, before somehow emitting a sound of false recognition. “I see her now. She’s cute,” I lied.

Mixed up in my feelings of jealousy, I also found myself contradictorily excited at the prospect of a protégé. If my brother didn’t want to play with me, it wouldn’t matter anymore because I would have my very own sister. I wrote letters to her, trying to psych myself up, but the clashing nature of my feelings only ever resulted in shame. I wanted desperately to silence my fears and be a good big sister, but I couldn’t help this mounting anxiety from getting in my way.

I tried to keep things as they were before, asking to skip school so I could lie in bed with my mom and watch movies all day. She’d sometimes let me, but I felt our bubble already significantly altered and her attention hard to place. In bed with her it was hard to ignore the growing belly between us, the place where my sister now lived. And I couldn’t help measuring myself against all the wonderful qualities I worried she’d have.

My body also experienced some scary changes around this time. I failed the vision test at school, and despite my desperate pleas that my eyes weren’t that bad, my mom bought me glasses anyway. I also saw that I now had dark brown hair on my arms, where other girls in class had smooth, pretty arms. My mom then noticed that I was often coming home from school with scraped knees and elbows from falling. When she took me to an orthopedic doctor and had me examined, his best diagnosis was clumsiness. All these things seemed serious to me. I felt as if my body were breaking down. I would be the ugly, nerdy, clumsy sister, and thoughts of self-loathing filled my head.

When Ashley finally climbed out of my mother’s womb that September afternoon, my growing fears intensified. A baby needs attention, after all, and as much as I tried to understand, my young mind was shattered at how much attention she actually demanded. My mom became fond of the camcorder, filming Ashley’s every move. My dad left work earlier to pitch in, and he spent lazy afternoons with her in the hammock that swung freely in the backyard sunshine. When I’d shop with my mom and the baby, I might end up with a blouse or pair of shoes, but if I noticed Ashley had more items than I, I fumed. Everyone at the mall fussed over her chubby cheeks and happy grin.

“Don’t you just love your little sister?” they’d exclaim, and I’d nod and produce an overly enthusiastic Yes!

Angry with my mom, my new sister, my brother, and my dad, I decided to throw myself into my academics. I excelled in all my subjects, especially language arts, and even found myself on the spelling bee team, studying lists of words all day and often before bed. I imagined myself becoming a national champ, my face on the cover of Time magazine. I would become the family genius.

Placing myself under enormous pressure, I became restless and squirmy. And I was nervous all the time. Nervous I would get bad grades and be held back another year, which meant being held back from the big, beautiful life I had planned for myself. Nervous I would make my parents mad about something and be banished to my bedroom without TV or books to suffer their worst punishment: Go to your room and think about what you did. But I was most nervous about upsetting God, the mighty ruler of the sky, more Nome King from Return to Oz than magic genie. If I upset God, then he would send me to hell, which was looking less like a fiery underworld and more like my bedroom in Montebello. For eternity.

My mom and dad were both impressed with my academic achievements, hanging up my Honor Roll and Student of the Month certificates on the fridge and proudly displaying my spelling bee trophies in the living room. I looked forward to after-school sessions with my fellow spelling bee enthusiasts, where we tested one another on words we didn’t even know the meaning of, eating burgers and drinking chocolate malts while we nursed lofty dreams of academic stardom. I belonged to a clique of smart, sensible achievers, and I felt comfortable there. For a while.

It wasn’t long before I noticed the intimacy of this clique and how the majority of the kids in class had no interest in words like pirouette or precipice. Their looks of boredom and back-row snickering were too intimidating to ignore, and so I purposely misspelled words and ignored my spelling bee comrades, becoming increasingly attached to a girl named Leslie, a popular tomboy who had blond hair and a surfer-dude inflection, despite her parents both being from Guadalajara, Mexico.

As Ashley grew into a little ball of energy and destruction around the house, tearing apart magazines and emptying drawers and cupboards out of curiosity while demanding every ounce of my mom’s wearying attention, Gabe spent more time out of the house with his friends and returned only to retreat to his room or roll his eyes at any of us should we try to interact with him. I tried to stay out of everyone’s way, continuing to excel at my academics in the most subtle way possible, so I didn’t receive any loud praise from teachers. I threw myself into my friendship with Leslie full force. Everything my mom did annoyed me, and I mimicked the way Leslie talked to her mom, rolling my eyes and protesting at simple chores, to her dismay.

We spent weekends watching movies like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and riding skateboards through the quiet residential streets of Whittier, where Leslie lived high up in the hills among big houses and hardly anyone spoke Spanish besides her family. I loved spending time in Whittier, and I wanted to hang out there all the time. Unlike Montebello, her neighborhood had antiques shops, a college, and white people. It wasn’t long before I started listening to the same music as Leslie—Nirvana, Pearl Jam, and Smashing Pumpkins—dressing like her, and talking like her. When I spent the night at her house, we stayed up late watching MTV before falling asleep in her bed, our bodies close and warm like conjoined twins.

When I think about the term first love, it’s difficult not to think of Leslie. My attachment to her was so intense, magnified by the urgency of youth, that the relationship still sticks out for me as one of the bigger ones in my life.

But I also recognize something dangerous and foreboding. I can’t help but realize that this relationship became a model of unhealthy love. With Leslie, I learned what it was to rely too heavily on another person, besides my mother, for security and comfort. I felt, for the first time, what it was to be completely enamored of a person, how being enamored can trick the brain into thinking it’s “in love,” and how being in love can sometimes feel the same as being completely swallowed up by that love until all that’s left when it’s over is a gaping hole just waiting to be filled again.

4 Philip Zimbardo writes in Man, Interrupted that gaming and porn have the capability of becoming what he calls “arousal addictions,” where the attraction is in the endless novelty and surprise factor of the content.

5 Advocates for Youth reported in “Parent-Child Communication: Promoting Sexually Healthy Youth” that many urban African-American and Latino mothers were reluctant to talk about sex with their preteen and early-adolescent daughters beyond biological issues and negative consequences. When maternal communications about sex were restrictive and moralistic in tone, daughters were less likely to confide in their mothers and sometimes became secretly involved in romantic relationships.

6 In a study by Kim S. Miller, Martin L. Levin, Daniel J. Whitaker, and Xiaohe Xu, called “Patterns of Condom Use Among Adolescents: The Impact of Mother-Adolescent Communication,” when mothers discussed condom use before teens initiated sexual intercourse, youth were three times more likely to use condoms. Furthermore, condom use at first intercourse greatly predicted future condom use—teens who used condoms at first intercourse were twenty times more likely than other teens to use condoms regularly.

7 The 2011 poll “Let’s Talk: Are Parents Tackling Crucial Conversations About Sex?” conducted by Planned Parenthood Federation of America and the Center for Latino and Adolescent Family Health shows that out of 1,111 nationally representative parents of youth ages ten to eighteen, only 43 percent of parents were comfortable having discussions about these issues with their kids. The reason? Their own parents had failed to talk to them, thus perpetuating a cycle of misinformation or a complete lack of information altogether.

I grew up in the early eighties in Montebello, California, Southeast LA, where teenage pregnancy was on the rise and every Mexican restaurant claimed to have the best tacos north of the border. Living rooms were adorned with framed pictures of Jesus or the Virgin, and everyone believed in heaven and hell—not as abstract ideas, but as very real places. It was the kind of place where you could pick up your holy candles with your milk and bread at the local supermarket and you always knew someone celebrating a baptism or First Communion soon—giant events requiring ornate outfits and tres leches cake and a sense of relief on everyone’s part that things were good with God, no one was going to hell just yet.

I rarely met anyone who wasn’t Catholic. When it did happen, it was whispered about. Did you know Mrs. Gonzalez is a Jehovah’s Witness? Isn’t that weird? If you weren’t Catholic, to whom would you turn for help? No priest? No Bible? It was unclear how a person could distinguish right from wrong without the Commandments. And I didn’t even want to think of what happened to them after death. I imagined babies dying before they were baptized and shuddered at their unfortunate fates.

I often tell people now that I come from LA, or sometimes East LA if I want to hint at my Latino roots. LA is Hollywood glamour, money, and prestige; East LA screams danger, gangs, and irrefutable street cred. In truth, my life had neither. Montebello and all Southeast LA, home to cities like Bell Gardens, Pico Rivera, and Norwalk, were small, mediocre, boring.

My dad, a mortgage broker, helped low-income Mexicans buy first homes, while my mom, a housewife, made sure our home was intact. They balanced their checkbooks, and we bought clothes at Ross, and the only place we traveled to outside of the country was Tijuana, which my mom often said “didn’t count” since it was only two hours south. My brother, Gabe, and I ran through sprinklers in the summer or laid down giant plastic trash bags for slipping and sliding. Katie Wilkins, a white girl, lived next door to us, which was rare in a predominately Mexican neighborhood, and I’d often peer at the swimming pool in her backyard from my bedroom window with envy. Mediocrity, which I felt was directly connected to my heritage, was my first source of shame.

But, in retrospect, we seem more privileged than I realized. I vacationed in Hawaii and Walt Disney World. I attended private Catholic school, from kindergarten through high school. My dad owned and ran a mortgage company for nearly twenty years until he sold it for a large sum and bought himself his dream car, a flashy Corvette that looked like the Batmobile, and a vacation condo in Maui. And by the time I entered high school we had moved into a house with a pool. I never knew what it was to go to bed hungry or face eviction, but shame has a way of being irrational. I looked at our life and I wanted more.

I simply couldn’t understand why my parents would want to live in such a boring place. There seemed to be nothing but strip malls and taco stands, nail salons and bail bonds. But to them, and to other Mexicans, Montebello was a big deal. In the late sixties and early seventies, when they were growing up, Montebello was nicknamed “the Mexican Beverly Hills.” Housing prices were more expensive and the streets were safer than those in nearby East LA, where my mom spent her formative years. Tomas Benitez, the Chicano author and activist, said in an interview with LA’s KCET, “Montebello was mythic when I was growing up in the 1970s. It was the place where middle-class Mexican-Americans lived and came from. It had that quality, if you could get out of East LA, Montebello was Nirvana, the promised land and Beverly Hills East all rolled into one location.”

For my dad, who was born under modest circumstances in Mexico City and whose own father was an orphan, to be able to live in the Mexican Beverly Hills as an adult was a big step up. He played golf at the city’s country club every weekend and served as an important figure in the city’s Rotary International organization. We often ran into people who knew and respected him wherever we went—restaurants, the bank, the supermarket—and they’d shake his hand with sincerity, reassuring me and my older brother, “Your dad’s a good man,” in case we ever doubted it.

My mom, on the other hand, was less interested in the community. She often complained about the city’s lack of good stores and its seemingly endless pavement. Sometimes she even complained about its propensity for attracting wetbacks, always laughing after this admittance, especially if my dad was around, before she’d lovingly touch his arm and coo, “Aww, I married a wetback.”

That term wetback, coined from those Mexicans who illegally crossed the Rio Grande to get to America, was not an accurate description of my dad, who had crossed the border legally and traveled by road, not river. But that didn’t stop my mom from muttering the word whenever she was feeling playful, or worse, when she was feeling wicked. Even though she has Mexican roots herself, I always thought that her teasing meant she considered natural-born citizens superior to those who had been naturalized. She would have likely picked this idea up from her own dad, a WWII veteran whose own parents were immigrants, and whose dark skin made him feel inferior in a country that was even harsher toward Mexicans than it is today.

The problem, for me, was that my neighborhood and my place inside it didn’t resemble my preconceived notions of power. It didn’t matter that my classmates at school shared the same Spanish-sounding last names and most of their grandmas didn’t speak English either. I took note of the Mexican guy selling oranges on the corner, and the busboy picking up our dishes topped with messes of ketchup and crumbs, and I thought, No, that’s not me. I even convinced myself now and again that I was superior to those kinds of Mexicans because my parents hadn’t taught me Spanish. We were outgrowing our Mexican-ness, I thought to myself. Pretty soon it would be gone completely, forgotten like a dream.

My feelings of superiority never lasted long. I knew my classmates and I were part of a minority, and I didn’t like the sound of that word, sitting heavy in my mouth and mind. I wanted to be like the blond-haired, blue-eyed Tanner girls on Full House. I wanted the calm, sensible family talks like the Seavers had on Growing Pains. I wanted a family tree that stretched back to Europe. Maybe England or Ireland, France even. But not Spain.

I got hooked on TV at a young age, marking the beginning of my intense bond with screens, and TV served as a window into the exciting world out there. I became obsessed with the families and neighborhoods I saw that were different from my own—which is to say, white. There was no George Lopez on TV then, no Sofia Vergara or America Ferrera. And I deemed the world “out there,” on the TV screen and in the heart of glittering Hollywood, to be far superior to the Mexican Beverly Hills with its baldheaded gangsters, its teenage mothers, and its paleta men making their living selling sweet treats to kids on clean, suburban pavement.

Unlike my dad, who seemed perfectly content with his roots and his chosen city of Montebello, I leaned more toward my mom’s chronic dissatisfaction and her fondness for escape. Like me, my mom also found herself captivated by screens. She loved foreign films—Cinema Paradiso, Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, Shirley Valentine—and I’d cuddle up with her on the couch for countless cinematic escapes, placing myself in the films and imagining the adventures waiting for me in adulthood.

Sometimes I would imagine taking trips with my mom. It’s not that I didn’t love my dad or that I wanted her to leave him forever, but maybe a few months? A year? I picked up on the tension that arose between my parents if my dad was working late again or on another client call. He usually returned from the office when we were already tucked into bed and was gone in the morning before we’d had a chance to get up, always trying to get ahead at the expense of my mom’s growing resentment. My brother and I got used to having my dad around only on the weekends. But even then there were always more phone calls, more stacked files in front of him, and my mom found this difficult to accept, alternating between giving him the silent treatment and erupting in angry outbursts, depending on her mood.

My mom’s moodiness became more pronounced as I grew older. Some days she’d park herself in front of the TV, bored eyes glazed over by some daytime talk show or murder mystery. Other days she’d take me to the mall to try on clothes and feast at the food court, deep-fried corn dogs with mustard and curly french fries. And yet other days she’d be annoyed by everything—the dirty dishes, the piles of laundry, her lazy children—and I’d think to myself, She just needs a break. If we go away for a little while, she’ll feel better.

When my mom was upset, I sought solace in playing video games with Gabe, who was three years my senior. We spent hours toting machine guns in Contra, gobbling up mushrooms in Super Mario Bros., and scouring mythic lands for Zelda. I became obsessed with trying to beat him, frantically studying video-game magazines to learn the latest cheats, training myself not to blink, lest I miss a bullet or fireball and lose. When I wasn’t playing, I was thinking of playing. When I was playing, I was thinking of what I’d play next.4

When we weren’t saving princesses in front of the TV screen, Gabe and I were putting ourselves on the screen, acting out short films he wrote and directed—he’d decided early on he was going to be a famous filmmaker when he grew up. Gabe’s gift for screenwriting and his skillfulness with my parents’ camcorder earned him a lot of admiration. Family parties invariably involved the screening of a movie Gabe was making with my cousins and me as actors, typically toward the end of the night when our parents were tipsy and jovial.

I came to resent what I saw as Gabe’s creative genius, even when my mom encouraged my rising interest in writing, buying me books and journals that I filled mostly with complaints about my brother intermingled with praise for all the boys I had crushes on at school. And whenever she caught me complaining about something being unfair, she’d murmur, smiling, “All the best writers had rough childhoods.”

When Gabe didn’t want to play with me, I’d terrorize him with kicks and shoves until he’d eventually shove me back, at which point I’d run crying to my mom in hopes he’d get punished. When she’d reprimand him, her long, curly hair shaking wildly around her face, I’d stand behind her, laughing and waving my hands at him, thinking, I win! She loves me more than you!

Despite my mom and dad’s persistent praise of Gabe, I clung desperately to the idea that my mom loved me more. We were girls, after all, and this meant something. That’s why she let me skip school and lie lazily in bed with her some days, watching movies and eating popcorn, saying, Don’t tell Dad I let you skip again. I loved keeping secrets with her.

One night, when I was ten years old, my parents told us kids we’d have dinner in our fancy dining room. I was confused. My dad rarely made it to dinner. I thought the dining room was reserved for Thanksgiving and Christmas only. And were those candles?

I had heard the word divorce slither out of my mom’s mouth on a few occasions when she was gossiping about my uncle’s ex-wife, or when she was talking about certain kids’ parents at school, and I wondered to myself if this is what was happening. Were my parents treating my brother and me to one final moment of togetherness before my dad packed up his suitcase? Would we be divided between them? Clearly I’d stay with my mom. And then, immediately after, I wonder where we’ll travel to first.

“Your dad and I have some big news,” my mom said, an excited smile on her face. A glass tumbler sat in her hand, filled to the brim with Pepsi and ice cubes, and she took gentle sips, letting suspense build around the table.

I looked at my dad, and he was smiling too.

“What is it?” Gabe said.

I kept my mouth shut, feeling excited yet guilty. Had I actually willed this into happening? Did all my imaginings of traveling the world with my mom come to fruition simply because I thought them? I considered the gravity of what this meant, that I had the power to destroy my parents’ marriage with my mind. I pictured myself as some kind of witch, a source of power and wickedness.

“You want to tell them?” my mom asked my dad.

“OK,” he said, and I held my breath.

“Your mom’s going to have a baby!”

My mom exploded in giggles, the ice cubes in her Pepsi clanking against the glass while she stood up to give me and my brother kisses and hugs. But when she pulled me close to her, my face pressed against her cotton blouse, I burst into tears.

“Oh, baby, why are you crying? What’s wrong?” She tried to pull away to look at my face, but I clung tight, digging my nails into her arm, refusing to let go. “Erica, what’s wrong?”

I heard my brother laugh, confused by my reaction. And I felt my dad come over beside us and put his warm hand on my quivering head. But I didn’t know how to explain the panic I felt at being cast aside, overshadowed by Gabe’s talent and the importance of a brand-new baby, and so I lied when they asked again, “Erica, why are you crying?”

Finally, I answered, “Because I’m happy.”

I can remember, vividly, the sexual fantasies that bubbled in my brain, seemingly out of nowhere, during my mom’s pregnancy. To distract myself from thinking about my new sibling, I turned my attention to other, more captivating places and daydreamed constantly. There’s nothing like the bulging belly and emotional intensity of a pregnant woman to inspire curiosity about how it all works—babies, sex, the origin of life.

All I had ever heard about sex from my parents came from my mom when, passing the local high school, she pointed out a few pregnant girls who couldn’t have been older than sixteen and said, “Don’t ever let that happen to you”—and then, pointing to my crotch—“don’t let anyone ever touch you down there.”

My mom and dad both seemed uncomfortable when it came to addressing sex, and they were equally as aggressive about hiding it from me.5 When things got hot and heavy in whatever movie we were watching, the response was immediate: “Close your eyes until we say,” and I complied, listening to the indistinct sounds of what I was not allowed to see until it was all over.

I can understand my parents’ reluctance at not wanting to talk about sex with me at ten years old, but “the talk” never came.6 Sex was something dirty and sinful, something to blush about, something to hide. These were obviously inherited ideas. My grandparents on both sides had the same reactions when a love scene unexpectedly danced across the TV screen: a shriek of discomfort followed by covered eyes and the demand that somebody change the damn channel. Whether it was a Latino thing7 or a Catholic thing, I couldn’t be sure. Even my teachers laughed uncomfortably and avoided eye contact when they explained that sex was something that happened “between two married people who loved each other,” for one reason alone: procreation.

Though I had limited knowledge of how sex worked, I began gradually piecing it together when my parents weren’t around. I’d been making lists of boys I wanted to kiss in my journal for a few years, but the lists became longer during my mom’s pregnancy, and sometimes even included rudimentary drawings of body atop body next to the lists. There seemed to be no one I didn’t find attractive in my fifth-grade class; I wanted all the boys—and some of the girls too—and even our teacher, Mr. Rivera.

In class, I’d stare at Mr. Rivera’s crotch, trying to imagine what he looked like under his clothes. I stared at my female teachers’ breasts and long legs. I stared at my classmates’ bodies with such unquenchable curiosity and thirst, but I had no idea what to do with this desire except to try and ignore it, though the bubbling in my brain proved difficult to control. And since no other girls were talking about this kind of thing, and I wanted desperately to be a good Catholic girl, I figured something terrible was happening to me.

Though I had attended Catholic school since kindergarten and weekly Mass was part of the curriculum, I didn’t pray much. I made the sign of the cross with holy water, I closed my eyes and folded my hands so I looked like I was deep in prayer, and I confessed to the priest when required (always the same sins: Bless me, Father, for I have sinned. I fought with my brother and I said bad words), but these rarely felt like real acts of faith. They were obligations. My parents didn’t pray much either. Not publicly, at least. For a short time, we attended Sunday Mass a few times a month, but then we turned into what my mom called “part-time Catholics,” attending only during the holiest events, like Christmas and Easter. Pretty soon, we stopped going completely, so Mass felt like another school period. Despite this lack of practice, when I found out my mom and dad were having the baby, I started praying for one thing daily: Please let the baby be a boy.

I had to maintain my specialness somehow, and being the only girl seemed the best route. I was already used to being the only girl, not only of my immediate family but also among all my cousins. When Gabe wrote a new screenplay, I naturally got all the female parts and I was the sole recipient of the kind of oohs and aahs that come with being the only kid wearing a pretty dress or sporting a new perm or having sparkly nails or whatever other girlie thing my mom bought for me that my aunts loved. I had a few female younger cousins, but they were too little to prove what good and pretty and polite little girls they were. I had that covered.

I wrote down my favorite little-brother names in my journal—Freddy or Jason, because I loved horror movies—and I knelt at the foot of my bed in tireless devotion to God, whom I thought of as a magic genie then, thinking, I will be a good girl forever if you grant me this one wish.

But God showed me what he thought of my wishes when my mom brought home the shadowy sonogram print of her new baby girl.

“Look at your little sister, Erica,” my mom said, handing over the picture. “Her name is Ashley.”

I held the print in my hand, terror rising in my throat as I tried to make sense of the black-and-white blob, before somehow emitting a sound of false recognition. “I see her now. She’s cute,” I lied.

Mixed up in my feelings of jealousy, I also found myself contradictorily excited at the prospect of a protégé. If my brother didn’t want to play with me, it wouldn’t matter anymore because I would have my very own sister. I wrote letters to her, trying to psych myself up, but the clashing nature of my feelings only ever resulted in shame. I wanted desperately to silence my fears and be a good big sister, but I couldn’t help this mounting anxiety from getting in my way.

I tried to keep things as they were before, asking to skip school so I could lie in bed with my mom and watch movies all day. She’d sometimes let me, but I felt our bubble already significantly altered and her attention hard to place. In bed with her it was hard to ignore the growing belly between us, the place where my sister now lived. And I couldn’t help measuring myself against all the wonderful qualities I worried she’d have.

My body also experienced some scary changes around this time. I failed the vision test at school, and despite my desperate pleas that my eyes weren’t that bad, my mom bought me glasses anyway. I also saw that I now had dark brown hair on my arms, where other girls in class had smooth, pretty arms. My mom then noticed that I was often coming home from school with scraped knees and elbows from falling. When she took me to an orthopedic doctor and had me examined, his best diagnosis was clumsiness. All these things seemed serious to me. I felt as if my body were breaking down. I would be the ugly, nerdy, clumsy sister, and thoughts of self-loathing filled my head.

When Ashley finally climbed out of my mother’s womb that September afternoon, my growing fears intensified. A baby needs attention, after all, and as much as I tried to understand, my young mind was shattered at how much attention she actually demanded. My mom became fond of the camcorder, filming Ashley’s every move. My dad left work earlier to pitch in, and he spent lazy afternoons with her in the hammock that swung freely in the backyard sunshine. When I’d shop with my mom and the baby, I might end up with a blouse or pair of shoes, but if I noticed Ashley had more items than I, I fumed. Everyone at the mall fussed over her chubby cheeks and happy grin.

“Don’t you just love your little sister?” they’d exclaim, and I’d nod and produce an overly enthusiastic Yes!

Angry with my mom, my new sister, my brother, and my dad, I decided to throw myself into my academics. I excelled in all my subjects, especially language arts, and even found myself on the spelling bee team, studying lists of words all day and often before bed. I imagined myself becoming a national champ, my face on the cover of Time magazine. I would become the family genius.

Placing myself under enormous pressure, I became restless and squirmy. And I was nervous all the time. Nervous I would get bad grades and be held back another year, which meant being held back from the big, beautiful life I had planned for myself. Nervous I would make my parents mad about something and be banished to my bedroom without TV or books to suffer their worst punishment: Go to your room and think about what you did. But I was most nervous about upsetting God, the mighty ruler of the sky, more Nome King from Return to Oz than magic genie. If I upset God, then he would send me to hell, which was looking less like a fiery underworld and more like my bedroom in Montebello. For eternity.

My mom and dad were both impressed with my academic achievements, hanging up my Honor Roll and Student of the Month certificates on the fridge and proudly displaying my spelling bee trophies in the living room. I looked forward to after-school sessions with my fellow spelling bee enthusiasts, where we tested one another on words we didn’t even know the meaning of, eating burgers and drinking chocolate malts while we nursed lofty dreams of academic stardom. I belonged to a clique of smart, sensible achievers, and I felt comfortable there. For a while.

It wasn’t long before I noticed the intimacy of this clique and how the majority of the kids in class had no interest in words like pirouette or precipice. Their looks of boredom and back-row snickering were too intimidating to ignore, and so I purposely misspelled words and ignored my spelling bee comrades, becoming increasingly attached to a girl named Leslie, a popular tomboy who had blond hair and a surfer-dude inflection, despite her parents both being from Guadalajara, Mexico.

As Ashley grew into a little ball of energy and destruction around the house, tearing apart magazines and emptying drawers and cupboards out of curiosity while demanding every ounce of my mom’s wearying attention, Gabe spent more time out of the house with his friends and returned only to retreat to his room or roll his eyes at any of us should we try to interact with him. I tried to stay out of everyone’s way, continuing to excel at my academics in the most subtle way possible, so I didn’t receive any loud praise from teachers. I threw myself into my friendship with Leslie full force. Everything my mom did annoyed me, and I mimicked the way Leslie talked to her mom, rolling my eyes and protesting at simple chores, to her dismay.

We spent weekends watching movies like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and riding skateboards through the quiet residential streets of Whittier, where Leslie lived high up in the hills among big houses and hardly anyone spoke Spanish besides her family. I loved spending time in Whittier, and I wanted to hang out there all the time. Unlike Montebello, her neighborhood had antiques shops, a college, and white people. It wasn’t long before I started listening to the same music as Leslie—Nirvana, Pearl Jam, and Smashing Pumpkins—dressing like her, and talking like her. When I spent the night at her house, we stayed up late watching MTV before falling asleep in her bed, our bodies close and warm like conjoined twins.

When I think about the term first love, it’s difficult not to think of Leslie. My attachment to her was so intense, magnified by the urgency of youth, that the relationship still sticks out for me as one of the bigger ones in my life.

But I also recognize something dangerous and foreboding. I can’t help but realize that this relationship became a model of unhealthy love. With Leslie, I learned what it was to rely too heavily on another person, besides my mother, for security and comfort. I felt, for the first time, what it was to be completely enamored of a person, how being enamored can trick the brain into thinking it’s “in love,” and how being in love can sometimes feel the same as being completely swallowed up by that love until all that’s left when it’s over is a gaping hole just waiting to be filled again.

4 Philip Zimbardo writes in Man, Interrupted that gaming and porn have the capability of becoming what he calls “arousal addictions,” where the attraction is in the endless novelty and surprise factor of the content.

5 Advocates for Youth reported in “Parent-Child Communication: Promoting Sexually Healthy Youth” that many urban African-American and Latino mothers were reluctant to talk about sex with their preteen and early-adolescent daughters beyond biological issues and negative consequences. When maternal communications about sex were restrictive and moralistic in tone, daughters were less likely to confide in their mothers and sometimes became secretly involved in romantic relationships.

6 In a study by Kim S. Miller, Martin L. Levin, Daniel J. Whitaker, and Xiaohe Xu, called “Patterns of Condom Use Among Adolescents: The Impact of Mother-Adolescent Communication,” when mothers discussed condom use before teens initiated sexual intercourse, youth were three times more likely to use condoms. Furthermore, condom use at first intercourse greatly predicted future condom use—teens who used condoms at first intercourse were twenty times more likely than other teens to use condoms regularly.

7 The 2011 poll “Let’s Talk: Are Parents Tackling Crucial Conversations About Sex?” conducted by Planned Parenthood Federation of America and the Center for Latino and Adolescent Family Health shows that out of 1,111 nationally representative parents of youth ages ten to eighteen, only 43 percent of parents were comfortable having discussions about these issues with their kids. The reason? Their own parents had failed to talk to them, thus perpetuating a cycle of misinformation or a complete lack of information altogether.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (January 9, 2020)

- Length: 224 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501163395

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Getting Off Trade Paperback 9781501163395

- Author Photo (jpg): Erica Garza Rachael Lee Stroud(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit