Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

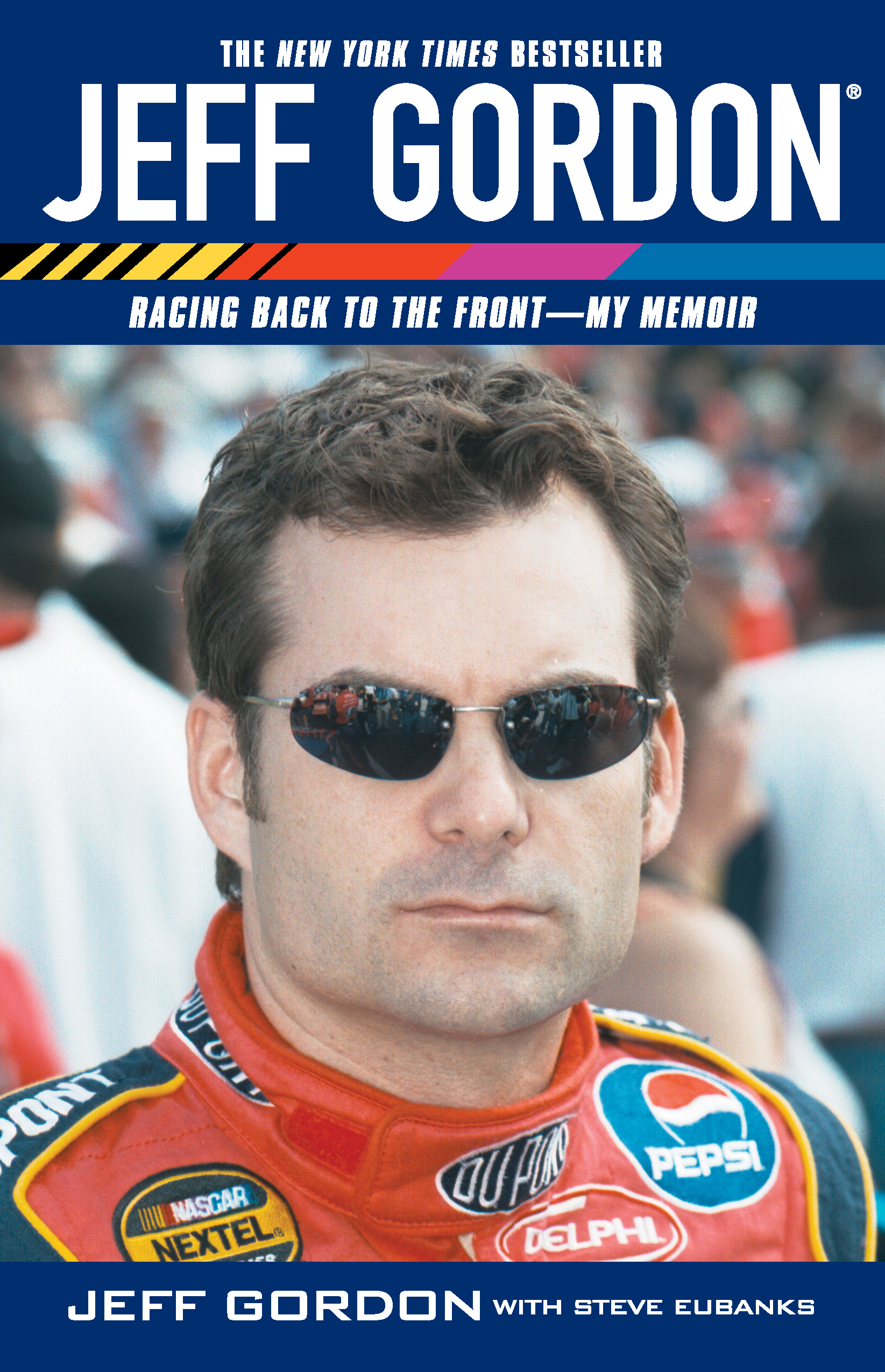

The New York Times bestselling autobiography of one of auto racing's greatest drivers—and a pedal-to-the-metal look at the life of a NASCAR champion.

He's the hottest thing on the racetrack today! In his professional racing career, Jeff Gordon has made the Winner's Circle his second home, taking the checkered flag with skill, determination, and a heartfelt love of racing—all while winning over more fans than any other driver in history and helping transform NASCAR racing into the most-watched entertainment in America.

Here, Jeff Gordon tells the story of his life behind the wheel: from his unlikely beginnings on the California junior circuit to his first professional win to his meteoric rise to fame—and all of the personal trials, triumphs, and roadblocks he faced along the way. Gordon also gives readers an up-close, high-speed look at what it's really like to climb into the cockpit of a stockcar every weekend and race for a championship; into the garages where his cars are made; and inside the lives and work of his extraordinary crew as his cars get built, tested, and driven to victory.

This is Jeff Gordon behind the helmet and in front of the pack—an inspirational, thrilling,and true story of courage and character from one of auto racing's greatest heroes.

INCLUDES 16 PAGES OF BLACK AND WHITE PHOTOS

He's the hottest thing on the racetrack today! In his professional racing career, Jeff Gordon has made the Winner's Circle his second home, taking the checkered flag with skill, determination, and a heartfelt love of racing—all while winning over more fans than any other driver in history and helping transform NASCAR racing into the most-watched entertainment in America.

Here, Jeff Gordon tells the story of his life behind the wheel: from his unlikely beginnings on the California junior circuit to his first professional win to his meteoric rise to fame—and all of the personal trials, triumphs, and roadblocks he faced along the way. Gordon also gives readers an up-close, high-speed look at what it's really like to climb into the cockpit of a stockcar every weekend and race for a championship; into the garages where his cars are made; and inside the lives and work of his extraordinary crew as his cars get built, tested, and driven to victory.

This is Jeff Gordon behind the helmet and in front of the pack—an inspirational, thrilling,and true story of courage and character from one of auto racing's greatest heroes.

INCLUDES 16 PAGES OF BLACK AND WHITE PHOTOS

Excerpt

Chapter One: Travel and Leisure

For most of us there is no such thing as typical week for a NASCAR team. My calendar is booked as far as nine months out, and there are few weeks where I can find anything resembling a pattern. I might be testing a car in Rockingham, North Carolina, on a Tuesday and shooting a promotional commercial for Pepsi the Tuesday after that. I could be in the shop meeting with Robbie and the crew this Wednesday, and the following Wednesday I might be in Wilmington, Delaware, for a DuPont appearance. I try to keep my calendar as organized as possible, but the only thing that's certain about my schedule is that there's rarely any downtime.

I try to segment my days into one-hour increments, and as I look at my calendar for the next month, almost every hour is blocked. That's why it's so hard for me to commit to anything at the last minute. The producers of Live with Regis and Kelly have asked me several times to fill in for Regis on his show, and while I've been able to do it a couple of times, there have been more times when I've had to turn them down. I use that as an example, because I love doing that show. I have a great time, I always meet interesting people, and it's good exposure for our sport and our sponsors. If I could say yes every time they call, I certainly would. But my commitments are such that I can't.

The only day I block out for myself is Monday. After the conclusion of a race I change out of my race suit, say good-bye to the team, and head to the airport, where I either fly home or scoot off to meet some friends. For the next twenty-four hours I try to do nothing but take care of myself. I might spend the day doing laundry or paying bills. I might go to Lake Norman outside Charlotte, go out on my boat. Sometimes I go to New York. I love the city because my friends and I can walk around, shop, eat, and for the most part be completely anonymous. I also love to dive, so I might go somewhere that I can spend a little time underwater. I bought a new car on a Monday; I do most of my banking on Mondays. Most of the things people do on their weekends or during vacations, I try to squeeze into Mondays.

I try to keep Tuesdays open so I can devote my full attention to those sponsors and media to whom I've committed, whether it's an appearance at a DuPont customer conference or a series of magazine interviews and photo shoots. Unfortunately, I can't say yes to every request. Jon Edwards, who fields most of my media contacts, estimates that I get a hundred requests a week, and he has to turn most of those down because of time. I don't like saying no, but I don't have any choice.

If we've scheduled a test for Tuesday, that's what I do; the car and the team come first no matter what. I'm fortunate to have sponsors who understand that, and they don't mind if I turn down an appearance request because of a test. Getting to Victory Lane is the most important thing for them as well as for us. We try to schedule appearances far enough in advance to avoid any conflicts, but on the few occasions when I'm being pulled in two different directions, our sponsors understand that I'm always going to err on the side of the car and the team.

When I first got in a Winston Cup car in late 1992, I tried to do everything for everybody. If a local reporter wanted an interview, I would call him back immediately and give him as much time as he needed. If a local auto parts store wanted me to do a one-hour appearance, I'd show up and give them as much time as they needed, even if the company didn't sponsor our car. At the time, that wasn't unusual. Most drivers worked out their own one-day or one-hour appearances. We were all trying to grow the sport, and I was trying to get my name out, so we did whatever we could to promote ourselves. A couple of years and a few hundred mistakes later, I realized I was spreading myself way too thin, and doing a disservice to the companies footing the bill for me to go racing. Some of my sponsors saw me doing these one-day autograph signings and wondered why they were writing such big checks when, for a daily rate, I would go anywhere for anybody. Now, I've chosen a few select sponsor/partners and work with them exclusively. I'm able to give them more time, attention, and exposure, and they don't have to worry about me being overextended and distracted. They're happy, and I'm happy.

That doesn't mean I don't have conflicts. I remember one Monday after a race in Kansas (a race I won), I scheduled a quick trip to Las Vegas for a Warner Brothers movie shoot. I was tired after racing five hundred miles, but the shoot was scheduled for 10 P.M. I figured I'd be on the plane heading home by midnight. What I didn't count on was all of the retakes pushing the shoot back five hours. By the time we started shooting my segment, it was 3 A.M. We finished a little after five, and I got back to Charlotte at 1 P.M. on Tuesday. So much for that day off.

Barring any other conflicts, Wednesday is my day to be in the Charlotte office and race shop. That might mean I spend the entire day meeting with Robbie and our team manager, Brian Whitesell, or I might spend the day with my business manager, Bob Brannan. Fortunately, my business offices are on the second floor of the building that houses the shop for the 24 car and the 48 car (driven by Jimmie Johnson, of which I'm also a co-owner). That puts my licensing operations, my fan club, the merchandizing division, and my foundations offices under the same roof as our mechanics, engineers, fabricators, and pit crew personnel, which works out great for me. I can spend the morning autographing die-cast cars for my foundation, have a quick in-house lunch with my business manager, and spend the afternoon going over next week's race with Robbie and Brian.

While in the Charlotte office, I make it a point to wander around the shop and speak to the guys. I don't intrude, and I certainly don't step on Robbie and Brian's managerial authority, but it's important that everyone in the shop see me and know that I don't just show up at the track on the weekends. I'm still learning a lot about the details of our sport, so it's good that I spend time with the guys who are putting the cars underneath me. I know a lot about the cars (I've been driving and working on cars since I was a kid), but I also know that the technology has advanced beyond my expertise. I rely on our mechanics and engineers to put the best and safest car on the track every week. But it's good for them to know that I'm there for them if they have any questions, or if they need to talk to me about anything.

Late in our 2002 season, for example, one of the guys in our fabrication shop, who also serves on the over-the-wall crew on race day, got an offer to go to another team. Robbie told me about the offer when I was in the shop, and I was able to get with Rick Hendrick and work out a counteroffer that allowed our guy to stay with us. That's part of what I do, now.

That hasn't always been the case. In my early days in Winston Cup, I was the driver and nothing more. The team was employed by Rick and answered to my first crew chief, Ray Evernham. I focused on what I knew, which wasn't running a race team. Now, Robbie and Brian are the bosses who make the day-to-day operational decisions. Rick and I are the co-owners. Someday, when I'm no longer driving, I'll become more involved in the operational side of things. Right now, I'm content to listen, learn, be around when I'm needed, and drive the car.

If a sponsor commitment forces me to miss my Wednesday shop appearance, I'll shuffle things around to be in the office on Tuesday, or Thursday before leaving for the track. I won't schedule a sponsor appearance for a Thursday unless it's on the way to a track. If we're scheduled to race in Talladega, Alabama, for example, and one of my sponsors wants me to appear in Birmingham, I look at that as a great opportunity. But if I'm racing in New Hampshire and the sponsor wants me to travel to Dallas on Thursday, I have to say, "I'm sorry. Hopefully we can do it some other time."

Having my own plane (or, rather, making finance payments on my own plane) helps. I don't have to go through the lines at commercial airports or work my travel around airline schedules. Currently I write checks to the bank for a Falcon 200, a midsize private jet. It's expensive, but when I look at the time I save, and the number of things I'm able to do for our team and for my sponsors because of the jet, I know it's worth every cent.

Usually the plane touches down somewhere near the racetrack on Thursday night, and the rest of my week is spent either driving the car or thinking about the race on Sunday.

The team's schedule is little more predictable, but no less strenuous. The team members who were not at the race the previous weekend (which is about seventy people, far and away the majority of the staff) get to work about six-thirty on Monday morning. At seven, they have a managers' meeting that includes Robbie; Brian; Joe Berardi, our head engineer; Ron Thiel, who, as I've mentioned, is also my spotter; Mark Thoreson, the shop foreman; Pete Haferman, our chief engineer; Wes Ayers, the fabrication shop manager; and Ken Howes, whom we fondly refer to as the "sage from South Africa." Ken, a native of Cape Town, is the competition manager for all Hendrick Motorsports teams, and a guy who knows more about racing than anyone else in the business. Nothing slips by him. Sometimes, especially if there are any big-picture issues to discuss, Rick Hendrick will sit in on these meetings.

At 7:25, the meeting breaks up, and the individual managers have meetings with the men and women in their departments. This is where the managers set the agenda for the day and give the team an overview of what to expect the rest of the week.

The race-day personnel, the guys who go over the wall, and who most novice fans assume compose our entire race team, take Monday off. They usually fly back to Charlotte on Sunday night, or, if the race was close by, they carpool home. Like me, they are usually spent when they hit their pillows on Sunday night. A day of rest and recovery is crucial to keep them fresh and motivated.

As for the bulk of the team -- the guys the public never sees, and the ones the novice NASCAR viewer never knew existed, but who are just as important -- their hands are full on Monday morning. By eight o'clock, the transporter has pulled into the shop and both cars (the primary car and the backup car from the previous race) have been unloaded. Four men, known as the postrace crew, spend Monday morning stripping the cars, taking out the suspension, removing the engine, washing the chassis, and bringing all the parts into a twelve-by-twenty-five-foot room known as the parts room. All the parts are inspected, cleaned, and serviced. Any unusual damage or wear is logged and reported to the crew chief, and the parts are all tagged for future reference. The suspension goes to another similarly sized room where it's also checked and cleaned.

At the same time, the car body is being washed in the back. After a thorough scrubbing by the crew, the body-shop manager comes out to inspect any damage. Even if I didn't crash the car, there are always dents and dings. A good clean race means we've had lots of fender rubbing and not-so-gentle nudges, all of which leave scars on the car. The body manager notes all of those blemishes and determines which parts must be repaired or replaced.

After a car goes through postrace, it's brought onto the main floor of the shop, where the mechanics put in a new engine and suspension and get it ready for its next outing. A five-hundred-mile race, plus practice and qualifying laps, at 180 miles an hour is all an engine and suspension can take. As for the chassis, the next outing might be in a couple of weeks or in a few months. Most fans know that teams have more than two cars, but I don't think many realize how many cars we have. Before the start of the 2003 season, we had as many as thirty cars (for both the 24 and 48 teams) on our shop floor at once. We have cars for superspeedways, cars for short tracks, cars for intermediate tracks, and cars for road courses. We have six cars specifically for the Daytona and Talladega, even though we only run four races a year at those two tracks. I used to give names to the cars, most starting with the letter B -- Boomer, Backdraft, Beavis, Butthead, and so on -- as a way of personalizing my relationship with the machines. If Boo has a good run in Rockingham, it will go through postrace and be set up for its next start, even though that might not be until we go back to Rockingham in three months' time.

On Tuesday morning the over-the-wall crew comes in, and the entire road crew, including the mechanics and the engineers who are at the track Thursday through Saturday, but who aren't a part of the over-the-wall crew on Sunday, meet with the crew chief to go over track notes from the previous race. Tire specialists, engineers, the gasman, the jackman, and all the mechanics go through every detail of the race. Did the tires wear the way we expected? Did the temperatures in the car stay where we thought they would? How did our lap times improve or get worse as we made various adjustments? What were the tire pressures and track conditions when we were running our fastest laps? How fast did we get in and out of the pits, and what can we do in the future to shorten those times by a fraction of a second? All these questions and dozens more are asked and answered during this Tuesday-morning session. Robbie and Brian have televisions and VCRs in their offices so they can view tapes of the race. If there was a screwup, everybody sees it over and over. If we had a particularly good run, it's analyzed and everybody gives input. It's an open and honest meeting, never hostile, with the main objective being to isolate and eliminate mistakes, and to enhance those things we did well.

After the meeting, the pit carts (those large boxes in the pits where the tools and parts are stored and on which the crew chief and the engineer sit during the race) are brought into the gear and suspension rooms. All the parts are removed and replaced with parts needed for the upcoming race. Just as we have different cars for different tracks, we have different parts and tools for different cars. Every drawer and cabinet in the transporter has to be emptied and restocked with the right parts for the week ahead, and the same is true for every square inch on the pit cart.

While part of the crew is setting up the pit carts, the mechanics and the engineers are preparing the primary car. Even though this car was cleaned and reassembled during postrace, the crew chief and engineers work on the skirts, the nose, and the shocks package, all the things we need to set the car up for the conditions we expect at the next race. In addition to being a mechanical genius, Robbie has to be a meteorologist, not to mention a fortune-teller, when he's putting these setups on the cars. If we're racing in Michigan in June, the weather might be sunny and eighty degrees, or it might be forty, cloudy, and miserable. He has to be ready for both, but he also has to set the car up for the conditions he expects when we arrive. Warm temperatures and low humidity might mean a stiffer shock and spring combination and little less air pressure in the tires; a hot, humid day might call for even softer tires, while a cold day might mean softer springs and more air in the tires. Sometimes we get it wrong, but more often than not, the team does a great job getting the car set up pretty close to perfect before it leaves the shop. That comes from years of experience at familiar tracks, and the most detailed notes you could imagine.

Wednesday and early Thursday morning, the crew sets up the backup car. By no later than midday on Thursday, the transporter is loaded and on the road. The early road crew, the mechanics and the engineers who are at the race for qualifying and practice, but are not part of the Sunday over-the-wall crew, fly out on one of the team planes. If they arrive early on Thursday, they check into their hotels and get a bite to eat. I'm usually not far behind. I get to the track around sundown and try to be settled into the motor coach by nine o'clock.

Friday, qualifying day, the over-the-wall guys and the Monday-through-Friday mechanics, fabricators, and engineers stay in the Charlotte shop. The over-the-wall guys might get in a few more practice sessions. We have a mock pit and a car behind the shop with cameras set up to capture every movement from every angle during a pit stop. The over-the-wall crew practices two -- and four-tire stops at least twice, and more often three, times a week. The tapes are reviewed, analyzed, and scrutinized just like NFL teams look at game films. When the over-the-wall crew goes home on Friday night, they're ready for the race.

Saturday is practice day at the track, our last chance to fine-tune the car and get it right before the green flag falls on Sunday. It is also the second day off for the over-the-wall crew, although most of them only take a half day off and travel to the track on Saturday night. The Charlotte staff takes both Saturday and Sunday off, which gives everyone at least two days off a week, something I think is important to building a long-term, successful race team. Sure, you can work people twelve hours a day, seven days a week, but not for three or four years. Race mechanics have families, and lives, bills to play, laundry to wash, dogs to walk, and other interests outside of racing. To attract and keep the best people, we've got to be conscious of those personal needs and go out of our way to be accommodating when we can. I think we do a good job at this.

There are exceptions, those weeks when everyone knows they have to pull double duty to get the job done. If we have back-to-back races in Rockingham and Las Vegas, for example, we don't have time to postrace the Rockingham cars and set up the Vegas cars in our standard schedule. It takes two days for the transporter to drive across the country, so the crew has to compress their schedule and set up both Rockingham and Vegas cars the same week. That way when the transporter rolls in on Sunday night, the team can unload and postrace the Rockingham cars and immediately load the Vegas cars while the truck driver gets a few hours' sleep. By late Monday night, the truck is ready to roll west.

No one complains when we work long, hard hours, although I've heard guys from other teams say that NASCAR should rearrange the schedule so we have a break after our West Coat stops. Our team has always adjusted to the schedule. Travel is a small price that we pay for expanding our sport into new markets. There isn't a person in our shop who wouldn't work a hundred hours a week if that was what it took to win. Knowing that fact inspires and pushes me to deliver every week when I get into the car. Everyone involved in the 24 car's crossing the finish line thirty-six Sundays a year -- those the public sees, and those who work out of the spotlight in our eighty-thousand-square-foot shop in Charlotte -- is critical to our team's success. It's a common saying because it's true: a chain is only as strong as its weakest link.

We travel together, work together, struggle together, lose together, and win together. Sure, I'm the guy the reporters want to talk to on Sunday, and I'm the guy who holds up the giant cardboard checks when we win, but I'm not naive or vain enough to think that I'm the sole reason we're successful. Racing is a team effort -- always has been, always will be.

Copyright © 2003 by Jeff Gordon, Inc.

For most of us there is no such thing as typical week for a NASCAR team. My calendar is booked as far as nine months out, and there are few weeks where I can find anything resembling a pattern. I might be testing a car in Rockingham, North Carolina, on a Tuesday and shooting a promotional commercial for Pepsi the Tuesday after that. I could be in the shop meeting with Robbie and the crew this Wednesday, and the following Wednesday I might be in Wilmington, Delaware, for a DuPont appearance. I try to keep my calendar as organized as possible, but the only thing that's certain about my schedule is that there's rarely any downtime.

I try to segment my days into one-hour increments, and as I look at my calendar for the next month, almost every hour is blocked. That's why it's so hard for me to commit to anything at the last minute. The producers of Live with Regis and Kelly have asked me several times to fill in for Regis on his show, and while I've been able to do it a couple of times, there have been more times when I've had to turn them down. I use that as an example, because I love doing that show. I have a great time, I always meet interesting people, and it's good exposure for our sport and our sponsors. If I could say yes every time they call, I certainly would. But my commitments are such that I can't.

The only day I block out for myself is Monday. After the conclusion of a race I change out of my race suit, say good-bye to the team, and head to the airport, where I either fly home or scoot off to meet some friends. For the next twenty-four hours I try to do nothing but take care of myself. I might spend the day doing laundry or paying bills. I might go to Lake Norman outside Charlotte, go out on my boat. Sometimes I go to New York. I love the city because my friends and I can walk around, shop, eat, and for the most part be completely anonymous. I also love to dive, so I might go somewhere that I can spend a little time underwater. I bought a new car on a Monday; I do most of my banking on Mondays. Most of the things people do on their weekends or during vacations, I try to squeeze into Mondays.

I try to keep Tuesdays open so I can devote my full attention to those sponsors and media to whom I've committed, whether it's an appearance at a DuPont customer conference or a series of magazine interviews and photo shoots. Unfortunately, I can't say yes to every request. Jon Edwards, who fields most of my media contacts, estimates that I get a hundred requests a week, and he has to turn most of those down because of time. I don't like saying no, but I don't have any choice.

If we've scheduled a test for Tuesday, that's what I do; the car and the team come first no matter what. I'm fortunate to have sponsors who understand that, and they don't mind if I turn down an appearance request because of a test. Getting to Victory Lane is the most important thing for them as well as for us. We try to schedule appearances far enough in advance to avoid any conflicts, but on the few occasions when I'm being pulled in two different directions, our sponsors understand that I'm always going to err on the side of the car and the team.

When I first got in a Winston Cup car in late 1992, I tried to do everything for everybody. If a local reporter wanted an interview, I would call him back immediately and give him as much time as he needed. If a local auto parts store wanted me to do a one-hour appearance, I'd show up and give them as much time as they needed, even if the company didn't sponsor our car. At the time, that wasn't unusual. Most drivers worked out their own one-day or one-hour appearances. We were all trying to grow the sport, and I was trying to get my name out, so we did whatever we could to promote ourselves. A couple of years and a few hundred mistakes later, I realized I was spreading myself way too thin, and doing a disservice to the companies footing the bill for me to go racing. Some of my sponsors saw me doing these one-day autograph signings and wondered why they were writing such big checks when, for a daily rate, I would go anywhere for anybody. Now, I've chosen a few select sponsor/partners and work with them exclusively. I'm able to give them more time, attention, and exposure, and they don't have to worry about me being overextended and distracted. They're happy, and I'm happy.

That doesn't mean I don't have conflicts. I remember one Monday after a race in Kansas (a race I won), I scheduled a quick trip to Las Vegas for a Warner Brothers movie shoot. I was tired after racing five hundred miles, but the shoot was scheduled for 10 P.M. I figured I'd be on the plane heading home by midnight. What I didn't count on was all of the retakes pushing the shoot back five hours. By the time we started shooting my segment, it was 3 A.M. We finished a little after five, and I got back to Charlotte at 1 P.M. on Tuesday. So much for that day off.

Barring any other conflicts, Wednesday is my day to be in the Charlotte office and race shop. That might mean I spend the entire day meeting with Robbie and our team manager, Brian Whitesell, or I might spend the day with my business manager, Bob Brannan. Fortunately, my business offices are on the second floor of the building that houses the shop for the 24 car and the 48 car (driven by Jimmie Johnson, of which I'm also a co-owner). That puts my licensing operations, my fan club, the merchandizing division, and my foundations offices under the same roof as our mechanics, engineers, fabricators, and pit crew personnel, which works out great for me. I can spend the morning autographing die-cast cars for my foundation, have a quick in-house lunch with my business manager, and spend the afternoon going over next week's race with Robbie and Brian.

While in the Charlotte office, I make it a point to wander around the shop and speak to the guys. I don't intrude, and I certainly don't step on Robbie and Brian's managerial authority, but it's important that everyone in the shop see me and know that I don't just show up at the track on the weekends. I'm still learning a lot about the details of our sport, so it's good that I spend time with the guys who are putting the cars underneath me. I know a lot about the cars (I've been driving and working on cars since I was a kid), but I also know that the technology has advanced beyond my expertise. I rely on our mechanics and engineers to put the best and safest car on the track every week. But it's good for them to know that I'm there for them if they have any questions, or if they need to talk to me about anything.

Late in our 2002 season, for example, one of the guys in our fabrication shop, who also serves on the over-the-wall crew on race day, got an offer to go to another team. Robbie told me about the offer when I was in the shop, and I was able to get with Rick Hendrick and work out a counteroffer that allowed our guy to stay with us. That's part of what I do, now.

That hasn't always been the case. In my early days in Winston Cup, I was the driver and nothing more. The team was employed by Rick and answered to my first crew chief, Ray Evernham. I focused on what I knew, which wasn't running a race team. Now, Robbie and Brian are the bosses who make the day-to-day operational decisions. Rick and I are the co-owners. Someday, when I'm no longer driving, I'll become more involved in the operational side of things. Right now, I'm content to listen, learn, be around when I'm needed, and drive the car.

If a sponsor commitment forces me to miss my Wednesday shop appearance, I'll shuffle things around to be in the office on Tuesday, or Thursday before leaving for the track. I won't schedule a sponsor appearance for a Thursday unless it's on the way to a track. If we're scheduled to race in Talladega, Alabama, for example, and one of my sponsors wants me to appear in Birmingham, I look at that as a great opportunity. But if I'm racing in New Hampshire and the sponsor wants me to travel to Dallas on Thursday, I have to say, "I'm sorry. Hopefully we can do it some other time."

Having my own plane (or, rather, making finance payments on my own plane) helps. I don't have to go through the lines at commercial airports or work my travel around airline schedules. Currently I write checks to the bank for a Falcon 200, a midsize private jet. It's expensive, but when I look at the time I save, and the number of things I'm able to do for our team and for my sponsors because of the jet, I know it's worth every cent.

Usually the plane touches down somewhere near the racetrack on Thursday night, and the rest of my week is spent either driving the car or thinking about the race on Sunday.

The team's schedule is little more predictable, but no less strenuous. The team members who were not at the race the previous weekend (which is about seventy people, far and away the majority of the staff) get to work about six-thirty on Monday morning. At seven, they have a managers' meeting that includes Robbie; Brian; Joe Berardi, our head engineer; Ron Thiel, who, as I've mentioned, is also my spotter; Mark Thoreson, the shop foreman; Pete Haferman, our chief engineer; Wes Ayers, the fabrication shop manager; and Ken Howes, whom we fondly refer to as the "sage from South Africa." Ken, a native of Cape Town, is the competition manager for all Hendrick Motorsports teams, and a guy who knows more about racing than anyone else in the business. Nothing slips by him. Sometimes, especially if there are any big-picture issues to discuss, Rick Hendrick will sit in on these meetings.

At 7:25, the meeting breaks up, and the individual managers have meetings with the men and women in their departments. This is where the managers set the agenda for the day and give the team an overview of what to expect the rest of the week.

The race-day personnel, the guys who go over the wall, and who most novice fans assume compose our entire race team, take Monday off. They usually fly back to Charlotte on Sunday night, or, if the race was close by, they carpool home. Like me, they are usually spent when they hit their pillows on Sunday night. A day of rest and recovery is crucial to keep them fresh and motivated.

As for the bulk of the team -- the guys the public never sees, and the ones the novice NASCAR viewer never knew existed, but who are just as important -- their hands are full on Monday morning. By eight o'clock, the transporter has pulled into the shop and both cars (the primary car and the backup car from the previous race) have been unloaded. Four men, known as the postrace crew, spend Monday morning stripping the cars, taking out the suspension, removing the engine, washing the chassis, and bringing all the parts into a twelve-by-twenty-five-foot room known as the parts room. All the parts are inspected, cleaned, and serviced. Any unusual damage or wear is logged and reported to the crew chief, and the parts are all tagged for future reference. The suspension goes to another similarly sized room where it's also checked and cleaned.

At the same time, the car body is being washed in the back. After a thorough scrubbing by the crew, the body-shop manager comes out to inspect any damage. Even if I didn't crash the car, there are always dents and dings. A good clean race means we've had lots of fender rubbing and not-so-gentle nudges, all of which leave scars on the car. The body manager notes all of those blemishes and determines which parts must be repaired or replaced.

After a car goes through postrace, it's brought onto the main floor of the shop, where the mechanics put in a new engine and suspension and get it ready for its next outing. A five-hundred-mile race, plus practice and qualifying laps, at 180 miles an hour is all an engine and suspension can take. As for the chassis, the next outing might be in a couple of weeks or in a few months. Most fans know that teams have more than two cars, but I don't think many realize how many cars we have. Before the start of the 2003 season, we had as many as thirty cars (for both the 24 and 48 teams) on our shop floor at once. We have cars for superspeedways, cars for short tracks, cars for intermediate tracks, and cars for road courses. We have six cars specifically for the Daytona and Talladega, even though we only run four races a year at those two tracks. I used to give names to the cars, most starting with the letter B -- Boomer, Backdraft, Beavis, Butthead, and so on -- as a way of personalizing my relationship with the machines. If Boo has a good run in Rockingham, it will go through postrace and be set up for its next start, even though that might not be until we go back to Rockingham in three months' time.

On Tuesday morning the over-the-wall crew comes in, and the entire road crew, including the mechanics and the engineers who are at the track Thursday through Saturday, but who aren't a part of the over-the-wall crew on Sunday, meet with the crew chief to go over track notes from the previous race. Tire specialists, engineers, the gasman, the jackman, and all the mechanics go through every detail of the race. Did the tires wear the way we expected? Did the temperatures in the car stay where we thought they would? How did our lap times improve or get worse as we made various adjustments? What were the tire pressures and track conditions when we were running our fastest laps? How fast did we get in and out of the pits, and what can we do in the future to shorten those times by a fraction of a second? All these questions and dozens more are asked and answered during this Tuesday-morning session. Robbie and Brian have televisions and VCRs in their offices so they can view tapes of the race. If there was a screwup, everybody sees it over and over. If we had a particularly good run, it's analyzed and everybody gives input. It's an open and honest meeting, never hostile, with the main objective being to isolate and eliminate mistakes, and to enhance those things we did well.

After the meeting, the pit carts (those large boxes in the pits where the tools and parts are stored and on which the crew chief and the engineer sit during the race) are brought into the gear and suspension rooms. All the parts are removed and replaced with parts needed for the upcoming race. Just as we have different cars for different tracks, we have different parts and tools for different cars. Every drawer and cabinet in the transporter has to be emptied and restocked with the right parts for the week ahead, and the same is true for every square inch on the pit cart.

While part of the crew is setting up the pit carts, the mechanics and the engineers are preparing the primary car. Even though this car was cleaned and reassembled during postrace, the crew chief and engineers work on the skirts, the nose, and the shocks package, all the things we need to set the car up for the conditions we expect at the next race. In addition to being a mechanical genius, Robbie has to be a meteorologist, not to mention a fortune-teller, when he's putting these setups on the cars. If we're racing in Michigan in June, the weather might be sunny and eighty degrees, or it might be forty, cloudy, and miserable. He has to be ready for both, but he also has to set the car up for the conditions he expects when we arrive. Warm temperatures and low humidity might mean a stiffer shock and spring combination and little less air pressure in the tires; a hot, humid day might call for even softer tires, while a cold day might mean softer springs and more air in the tires. Sometimes we get it wrong, but more often than not, the team does a great job getting the car set up pretty close to perfect before it leaves the shop. That comes from years of experience at familiar tracks, and the most detailed notes you could imagine.

Wednesday and early Thursday morning, the crew sets up the backup car. By no later than midday on Thursday, the transporter is loaded and on the road. The early road crew, the mechanics and the engineers who are at the race for qualifying and practice, but are not part of the Sunday over-the-wall crew, fly out on one of the team planes. If they arrive early on Thursday, they check into their hotels and get a bite to eat. I'm usually not far behind. I get to the track around sundown and try to be settled into the motor coach by nine o'clock.

Friday, qualifying day, the over-the-wall guys and the Monday-through-Friday mechanics, fabricators, and engineers stay in the Charlotte shop. The over-the-wall guys might get in a few more practice sessions. We have a mock pit and a car behind the shop with cameras set up to capture every movement from every angle during a pit stop. The over-the-wall crew practices two -- and four-tire stops at least twice, and more often three, times a week. The tapes are reviewed, analyzed, and scrutinized just like NFL teams look at game films. When the over-the-wall crew goes home on Friday night, they're ready for the race.

Saturday is practice day at the track, our last chance to fine-tune the car and get it right before the green flag falls on Sunday. It is also the second day off for the over-the-wall crew, although most of them only take a half day off and travel to the track on Saturday night. The Charlotte staff takes both Saturday and Sunday off, which gives everyone at least two days off a week, something I think is important to building a long-term, successful race team. Sure, you can work people twelve hours a day, seven days a week, but not for three or four years. Race mechanics have families, and lives, bills to play, laundry to wash, dogs to walk, and other interests outside of racing. To attract and keep the best people, we've got to be conscious of those personal needs and go out of our way to be accommodating when we can. I think we do a good job at this.

There are exceptions, those weeks when everyone knows they have to pull double duty to get the job done. If we have back-to-back races in Rockingham and Las Vegas, for example, we don't have time to postrace the Rockingham cars and set up the Vegas cars in our standard schedule. It takes two days for the transporter to drive across the country, so the crew has to compress their schedule and set up both Rockingham and Vegas cars the same week. That way when the transporter rolls in on Sunday night, the team can unload and postrace the Rockingham cars and immediately load the Vegas cars while the truck driver gets a few hours' sleep. By late Monday night, the truck is ready to roll west.

No one complains when we work long, hard hours, although I've heard guys from other teams say that NASCAR should rearrange the schedule so we have a break after our West Coat stops. Our team has always adjusted to the schedule. Travel is a small price that we pay for expanding our sport into new markets. There isn't a person in our shop who wouldn't work a hundred hours a week if that was what it took to win. Knowing that fact inspires and pushes me to deliver every week when I get into the car. Everyone involved in the 24 car's crossing the finish line thirty-six Sundays a year -- those the public sees, and those who work out of the spotlight in our eighty-thousand-square-foot shop in Charlotte -- is critical to our team's success. It's a common saying because it's true: a chain is only as strong as its weakest link.

We travel together, work together, struggle together, lose together, and win together. Sure, I'm the guy the reporters want to talk to on Sunday, and I'm the guy who holds up the giant cardboard checks when we win, but I'm not naive or vain enough to think that I'm the sole reason we're successful. Racing is a team effort -- always has been, always will be.

Copyright © 2003 by Jeff Gordon, Inc.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria Books (March 29, 2005)

- Length: 272 pages

- ISBN13: 9780743499774

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Jeff Gordon Trade Paperback 9780743499774(3.4 MB)