Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

Psychedelics and Mental Health

Neuroscience and the Power of Psychoactives in Therapy

Table of Contents

About The Book

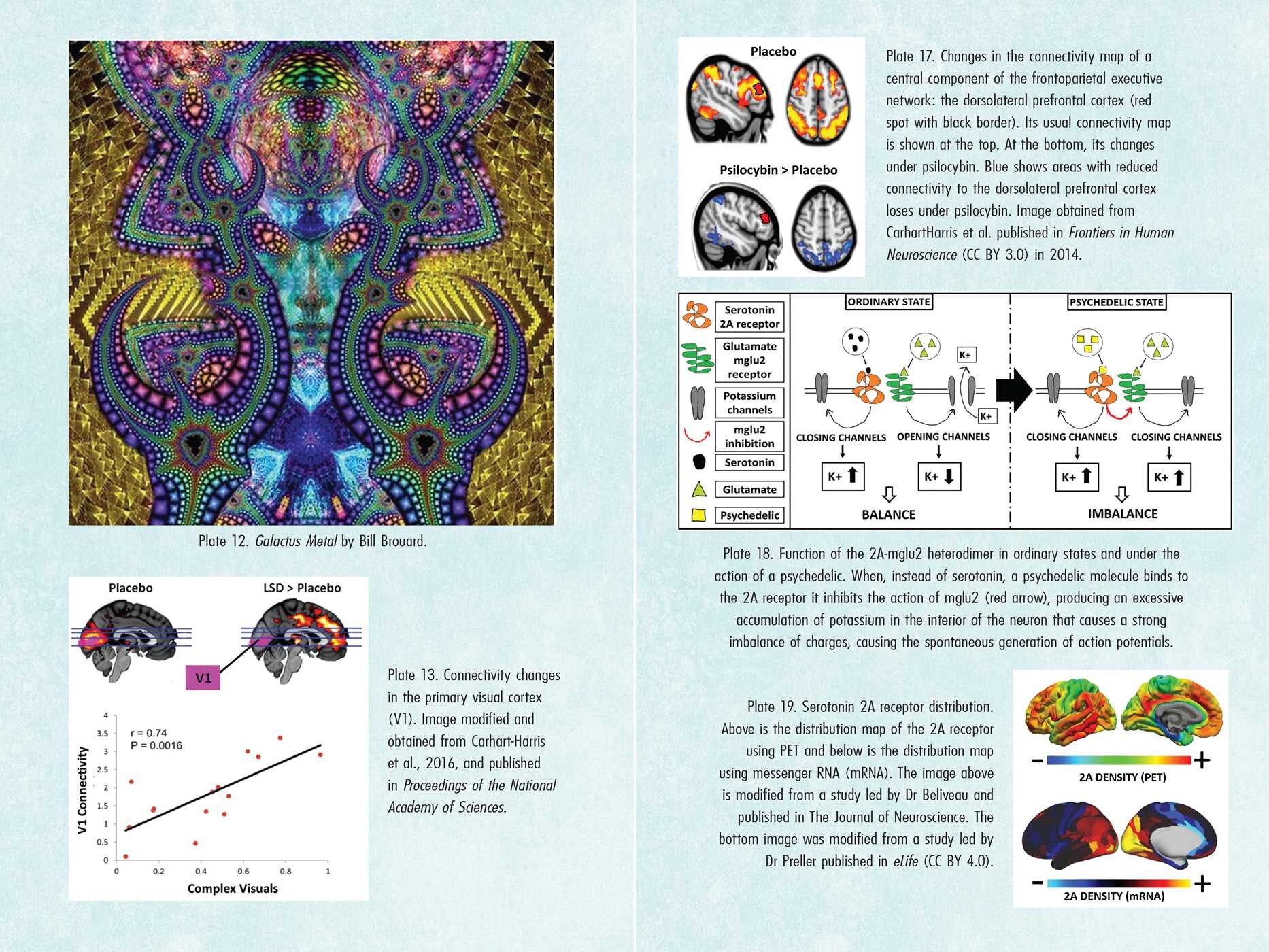

• Details how psychedelics alter our experience from a neurological perspective, including what neurons they interact with, their effects on cognitive and emotional processing, and why those effects can be therapeutic

• Looks at clinical results with LSD, psilocybin from magic mushrooms, and DMT from ayahuasca, as well as empathogens such as MDMA, found in ecstasy

• Provides an illustrated introduction to neuroscience and a vision for a new model of psychotherapy where psychedelics help bring lasting healing

Presenting a comprehensive guide to the new and evolving landscape of psychedelic-assisted mental health treatment, neuroscientist Irene de Caso takes you on a journey through the brain, revealing how psychedelics and empathogens, if taken in a safe and therapeutic environment, can lead to positive and lasting changes.

Providing an illustrated introduction to neuroscience and molecular actions in the body and brain, the author details how psychedelics alter our experience, including their effects on cognitive and emotional processing and how those effects can be therapeutic. She explores the wide body of evidence behind the psychedelic revolution in psychiatry and psychotherapy and looks at clinical studies on hallucinogens such as LSD, psilocybin from magic mushrooms, and DMT from ayahuasca as well as empathogens such as MDMA found in ecstasy. She reviews the efficacy of psychedelics in treating alcoholism and other addictions, post-traumatic stress disorder, social anxiety in autistic individuals, treatment-resistant depression, and other conditions, offering statistical comparisons to conventional antidepressants and mood-enhancing drugs. She also explores the psychedelic experience through neuroimaging and phenomenological experience, considering mystical states, synesthesia, and the therapeutic benefits of momentary ego-dissolution.

Laying the foundation for a new model of psychotherapy, de Caso shows how psychedelics can help break down our defense mechanisms, offer direct access to the subconscious, and provide a path to deeper, lasting healing.

Excerpt

Unlocking the Therapeutic Power of Psychedelics

How does one begin writing a book? I close my eyes and take a deep breath, feeling that silent inner core whose existence I ignored a few years ago. And I wonder, would I have ever discovered it had I never tried psychedelics? I doubt it. How can someone start searching for something if they don’t know it exists?

Now that mindfulness and meditation have reached the mainstream in the West, many people are discovering that other way of being and feeling, that inner core, through these avenues. However, at least on this side of the planet, this phenomenon was, undoubtedly, sparked by the countercultural movement of the 1960s brought about by the recreational use of LSD. Even today, when most people have already heard about meditation, many, myself included, only began to understand its value after having lived the psychedelic experience.

Suddenly, spiritual cliches previously devoid of meaning make perfect sense. One clearly understands the oneness of humanity and that of the holy whole. And, by sharpening the sensations related to breathing, paying attention to the present moment, and slowing down the inner dialogue, one obtains a deep and unimaginable peace. But unlike meditation, through which achieving such a revelatory experience usually requires years of practice, with psychedelics it is often just a matter of taking the right dose in the right environment.

It is not surprising that experiences of this nature have the potential to bring about psychological well-being. However, as we shall see, this is not always the case. Unlike meditation, the psychedelic experience also has the potential to promote high levels of anxiety, intense panic, and even psychotic breaks, especially when abused or conducted in the wrong environment. As with so many other decisions in life, it all comes down to assessing the risk-benefit balance and acting responsibly. And, it is my opinion that, for many people, the benefits outweigh the risks.

A Mental Health Crisis

Despite the fact that famines have all but disappeared in the West, there’s easy access to clean water, and death from disease and violence has been drastically reduced, there is no doubt that Western society is facing a serious mental health crisis. According to the INE (the Spanish National Institute of Statistics), ten people per day were already committing suicide in Spain before the pandemic—ten times more than the number of deaths due to traffic accidents!

Trauma, loneliness, and chronic stress. And a profound lack of meaning. Millions of people live kidnapped by their emotions. Possessed by them, some would say. Unable to be the masters of their behavior. We all experience this to a greater or lesser extent, but, why are some more resilient and able to better regulate their emotions than others? What is it that human beings require to heal their wounds and enjoy am life full of meaning?

The many available anxiolytics, antidepressants, psychotherapeutic techniques, and even the newly arrived and welcomed mindfulness practices, do not seem to be enough. Despite their undeniable utility,

these tools seem to be failing for a disturbingly large number of people. Psychotherapy is expensive and time consuming, and psychotropic drugs often have unpleasant side effects. What is more, even in the absence of side effects and with time and money at their disposal, many patients are still unable to free themselves from a constant sense of deep fear and suffering. Could highly stigmatized substances associated with the world of nighttime debauchery be the new tool we so desperately need?

As we shall see, this may indeed be the situation we find ourselves in. But what substances are we referring to exactly? How should they be used? What psychopathologies could be treated with such molecules? How do they work?

Throughout this book, we will focus on two types of persecuted substances whose research in psychotherapeutic settings has exploded in the last decade: classic psychedelics, such as LSD, psilocybin, and DMT (commonly known as hallucinogens); and the empathogen MDMA (commonly known as ecstasy), which is considered an atypical or pseudopsychedelic.

The Discovery, Prohibition, and Rebirth of New Tools in Psychotherapy

Nowadays most ordinary citizens associate substances such as LSD, magic mushrooms, and the famous ecstasy, with recreational environments. Although more and more people are becoming aware of their therapeutic applications, very few know that it was within a clinical setting where they first appeared. However, they eventually escaped from the laboratories and entered the world of leisure, which culminated in their subsequent illegalization and stigmatization. It is for this reason that the recent return of these substances to the research institutions is being called “the psychedelic renaissance,” given that there was already extensive research into their psychotherapeutic potential in the past. With the advent of the Controlled Substances Act and the beginning of the war on drugs, promoted by Nixon in the early 1970s, such research was, however, abruptly halted and the regulatory agencies of the time placed both molecules (first LSD and later MDMA) in the Schedule I category (the same category as heroin!). This is where substances supposedly devoid of medical use, considered dangerous even under supervision, and having a high potential for abuse, are placed. Why were they placed here?

Such classification was mainly motivated by political and social reasons rather than based on medical evidence. The psychedelic experience was leading young people to demonstrate against the Vietnam War and the materialistic culture, revolutionizing American society, and threatening the social order of the time. It would, however, be unfair to ignore that the careless use of psychedelics was spreading throughout the youth, causing frequent accidents and traumatic experiences in users. Nevertheless, studies carried out with LSD and MDMA under controlled settings were pointing to an important medical potential that was, either intentionally or accidentally, ignored by the legislators when they decided to classify them into the Schedule I category. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves and instead return to the beginning of these molecules’ fascinating discovery.

Lysergic acid diethylamide, known as LSD, was first synthesized by the chemist Albert Hofmann in 1938. At the time, Hofmann was working for Sandoz, a pharmaceutical company based in Basel, Switzerland. They were trying to find a treatment for migraines, searching for molecules with vasostimulant properties in ergot (a fungus that infects rye). However, animal studies revealed no effects, other than a certain behavioral agitation, so further research was discontinued.

However, for some mysterious reason, five years later this molecule was still present in the chemist’s mind, as he had a “peculiar presentiment” that the molecule hid some interesting properties. In retrospect, he recounts how it was not he who chose LSD but LSD who “found” him and “called” him. On April 16, 1943, he proceeded to repeat his synthesis, despite Sandoz having a strict policy against resuming research with substances that had been previously discarded.

It was during the last synthesis processes that Hofmann began to feel the first unusual sensations. A certain agitation and dizziness seized his body, forcing him to interrupt his work and go home to rest. Once there, lying on the sofa, he began feeling a certain intoxication, which he described as not unpleasant. On closing his eyes “an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colours” occupied his mind, eventually concluding that he must have absorbed a small amount of the substance he’d been working with.

Intrigued as to how a molecule could have such a powerful psychoactive effect, three days later he ventured to take 0.25 mg in a controlled manner under the supervision of his laboratory assistant. Such an experimental dose was seemingly minuscule. However, we now know that it corresponded to a very high dose of LSD, the usual dose being about 125 micrograms. Hofmann was about to experience the first LSD trip in history. After forty minutes, he began to feel the first effects, which he describes in his laboratory notebook as “dizziness, feeling of anxiety, visual distortions, symptoms of paralysis, desire to laugh,” these being the first and last notes he was able to take on that historic day.

Frightened by the intensity of the experience, he asked his assistant to accompany him home. Since it was wartime and transportation by car was forbidden, he used his bicycle. From then on, April 19 has become a day of celebration within the psychedelic community, known as Bicycle Day, and the bicycle, a representative icon of LSD.

No wonder this first LSD trip, not only given its potency but also given the absolute lack of knowledge regarding its toxicity, was terrifying for Hofmann. Seeing his reality drastically transformed and his volition vanished, he believed he had gone hopelessly insane, as if possessed by a demon. His assistant called a doctor who measured his vital signs and found nothing unusual other than an excessive dilation of the pupils and, gradually, he returned to ordinary reality. Imagine his relief as the danger of insanity faded away! As he enjoyed the still present visual effects, the feelings of terror were replaced by a profound sense of fortune and gratitude. He finally managed to sleep, and, when waking up the next day, he felt splendid, perceiving the vibrant world “as if newly created.”

Product Details

- Publisher: Park Street Press (February 27, 2025)

- Length: 336 pages

- ISBN13: 9798888500002

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“An extraordinary blend of scientific rigor and personal insight. This book masterfully conveys the neuroscience behind psychedelics, highlighting their promise for transforming mental health care.”

– Amanda Feilding, founder and director of the Beckley Foundation

“Neuroscientist Irene de Caso shows how psychedelics, when used safely and appropriately, can lead to positive and lasting change. This is an important book for anyone interested in the science of psychedelic-assisted mental health treatment.”

– Rick Doblin, Ph.D., founder and president of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studi

“Featuring illustrations, diagrams, and flowcharts, Psychedelics and Mental Health clearly guides the reader step-by-step along neuropsychological pathways that have previously baffled ordinary, nonscientific readers. By making ideas clear to both the sciences and the humanities, this book bridges the ‘two-cultures chasm.’”

– Thomas B. Roberts, Ph.D., author of Mindapps, The Psychedelic Future of the Mind, and Psychedelics a

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Psychedelics and Mental Health 2nd Edition, Revised Edition Trade Paperback 9798888500002