Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

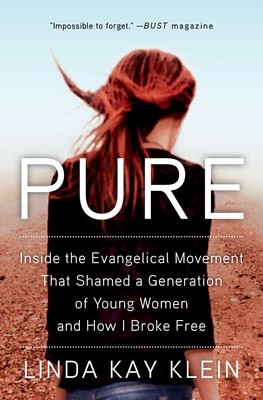

Pure

Inside the Evangelical Movement That Shamed a Generation of Young Women and How I Broke Free

Table of Contents

About The Book

In the 1990s, a “purity industry” emerged out of the white evangelical Christian culture. Purity rings, purity pledges, and purity balls came with a dangerous message: girls are potential sexual “stumbling blocks” for boys and men, and any expression of a girl’s sexuality could reflect the corruption of her character. This message traumatized many girls—resulting in anxiety, fear, and experiences that mimicked the symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder—and trapped them in a cycle of shame.

This is the sex education Linda Kay Klein grew up with.

Fearing being marked a Jezebel, Klein broke up with her high school boyfriend because she thought God told her to and took pregnancy tests despite being a virgin, terrified that any sexual activity would be punished with an out-of-wedlock pregnancy. When the youth pastor of her church was convicted of sexual enticement of a twelve-year-old girl, Klein began to question purity-based sexual ethics. She contacted young women she knew, asking if they were coping with the same shame-induced issues she was. These intimate conversations developed into a twelve-year quest that took her across the country and into the lives of women raised in similar religious communities—a journey that facilitated her own healing and led her to churches that are seeking a new way to reconcile sexuality and spirituality.

Pure is “a revelation... Part memoir and part journalism, Pure is a horrendous, granular, relentless, emotionally true account" (The Cut) of society’s larger subjugation of women and the role the purity industry played in maintaining it. Offering a prevailing message of resounding hope and encouragement, “Pure emboldens us to escape toxic misogyny and experience a fresh breath of freedom” (Glennon Doyle, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Love Warrior and founder of Together Rising).

Excerpt

As a teenager, I went to the sandbox in the empty playground beside my church when I wanted to be alone. I dug my bare feet down deep, cooling them in the damp sand.

“God, I would do anything for you,” I remember saying there one afternoon.

“Anything?” I imagined God’s reply.

“Anything,” I promised.

“Would you become a missionary in a foreign land?” God tested me. “Giving up the lavish life of an actress that you dream about?”

I squeezed my eyes shut and pictured myself a poor missionary living in a small, rural village somewhere on the other side of the world. In my imagination, I wore a thin, cotton dress and my long brown hair whipped around my face in a way that could only be described as romantic.

No, I shook my head abruptly. Not like that. God is asking if I’m willing to make a sacrifice for him,I I reminded myself. I could become deathly ill from serving the sick; I might not have access to clean drinking or bathing water; I might spend days working in the hot sun without any protection. I imagined my dress dirty and the skin under it covered in burns and unidentifiable wounds. Satisfied with this new image, I opened my eyes and looked back into the sun.

“Yes God,” I promised. “I would do that for you.”

“Would you give up your parents?” God continued.

“Yes,” I said quickly.

“Would you give up . . . your boyfriend?”

I winced.

“Who you think about all day and every night?” God continued. “Who makes you feel so utterly alive every time he touches you? Who you are sure is sin incarnate, even if he is a born-again Christian and thus ‘technically’ safe to date, and sure, all you’ve ever done is kiss, but the way he makes you feel . . . the way he makes you feel, you know must be wrong?”

“Yes,” I whimpered. “Yes, God. I would.”

Later that afternoon, I called my girlfriends for an emergency concert of prayer.II

“I think that God wants me to break up with Dean,” I told them, trembling. Not one of them asked me why. They didn’t have to. After all, we’d learned together that there were two types of girls—those who were pure and those who were impure, those who were marriage material and those who were lucky if any good Christian man ever loved them, those who were Christian and those who . . . we’re not so sure about. So, God wanting me to break up with a high school boyfriend who made my whole body scream every time he looked at me?

Yeah.

Sure.

That made sense.

It’s only now, more than twenty years later, that I can see another story beneath the only one my friends and I were able to see then. It’s the story of me—a sixteen-year-old girl in her first real relationship. Willing, no, wanting to be tested so she could prove to her God, her community, and herself that she was good.

After all, my sexual energy, sometimes off-color humor, and the ’50s pinup va-va-voom of the hips I’d recently acquired were already worrying some in my community. If I wasn’t careful, they warned me, I might just become a stumbling block. And maybe I already was one.

In the Bible, the term stumbling block is used to reference a variety of obstructions that can be placed before a Christian. The concept is used in reference to sexuality just once: “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall not commit adultery’; but I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lust for her has already committed adultery with her in his heart. If your right eye makes you stumble, tear it out and throw it from you; for it is better for you to lose one of the parts of your body, than for your whole body to be thrown into hell.”1

Yet, in the years I spent as an evangelical Christian, I never once heard anyone use the term the way it’s used here—in reference to the onlooker’s lustful eye. Instead, I heard it used time and time again to describe girls and women who somehow “elicit” men’s lust.III As I have heard it said, sometimes our interpretations of the Bible say more about us than they do about the Bible itself.

In junior high, the term stumbling block annoyed me. The implication that my friends and I were nothing more than things over which men and boys could trip was not lost on me. When half the guys stripped their shirts off and began a water fight at the youth group carwash outside of the Piggly Wiggly, I thought it was unfair that it was me who got reprimanded for having my shirt sprayed by their hoses. But even as I bristled, I obeyed. I went home and changed into a dry shirt, longer shorts, longer skirts, higher backed dresses, and higher necked tops. By the time I was in high school and had my first boyfriend, I had been “talked to” about how I dressed and acted so many times that my annoyance was beginning to turn into anxiety. It began to feel like it didn’t matter what I did or wore; it was me that was bad.

In the evangelical community, an “impure” girl or woman isn’t just seen as damaged; she’s considered dangerous. Not only to the men we were told we must protect by covering up our bodies, but to our entire community. For if our men—the heads of our households and the leaders of our churches—fell, we all fell.

Imagine growing up in a castle and hearing fables about how dragons destroy villages and kill good people all your life. Then, one day, you wake up and see scales on your arms and legs and realize, “Oh my God. I am a dragon.” For me, it was a little like that. I was raised hearing horror stories about harlots (a nice, Christian term for a manipulative whore) who destroy good, God-fearing men. And then one day, my body began to change and I felt sexual stirrings within me and I thought, “Oh no. Is that me? Am I a manipulative whore?”

My Diary—May 1995:

My senses are never so alive as they are when I’m with Dean. I don’t deserve this happiness. We sit across from one another, and we are so close that our cheeks rub up against each other. If he shaves in the morning, he is already ruff by evening. I rub his back. He rubs mine. It is sweet. It is innocent. But can we be moving too quickly even in the midst of our innocence?

“I think you have gotten prettier since I first met you,” Dean said to me.

“I don’t think so.”

“I do. You used to be pretty, but now . . .” He took a deep breath and gazed at me.

“You are so beautiful,” Dean mused, as he rubbed my face tenderly. He is always touching my face. It makes me feel precious.

“What do you think it means to fall in love?” I asked him.

“I don’t know,” he answered me.

“Do you think it’s possible that I could be falling in love with you? Puppy love?”

He kissed me.

“Do you think it’s possible,” I spoke the words between kisses, “that you,” a long kiss, “could be falling in love with me . . . puppy love?”

“Puppy love,” he answered me.

I am in the middle of reading Passion and Purity: Learning to Bring Your Love Life Under Christ’s Control by Elisabeth Elliot in my small group right now. In it she says that her husband Jim touched her for the first time by rubbing his finger across her cheek. AFTER he was already her fiancé.

So what does that mean? Once again, I worry that Dean and I are moving too quickly. We have already French kissed. You know, with tongue and all. Yeah, that’s too fast.

Dear Jesus, Dean is a sweet gift from You. Please don’t allow me to destroy this gift that You have given me with foolish passion. Dean doesn’t want to push me. He respects me. How far we go is in my hands. But I don’t want it there, because I don’t know where exactly You do and don’t approve of my hands being . . . Father, please show me what is “too far.”

This is going to sound disgusting, but when Dean rubs his face in my hair or breathes into my ear, my groin kind of flips. I don’t know how else to put it. Is that what it means to be “turned on”? I don’t know.

Have I turned into a slut? I feel dirty and worthless. How can respect exist when I am such a slut?

A slut.

What is one?

Who is one?

I am not a slut.

Nobody is a slut.

That is a despicable word.

But how dare I call myself a Christian? I spent my morning primping. I spent my afternoon making out with my boyfriend. Then I spent my evening leading a Bible study!

My girlfriends rushed over to my parents’ house for the concert of prayer. We sat in a circle on the floor of my parents’ basement, bowed our heads, and together asked for God to help me fulfill his command: To break up with Dean.

When the last of them later filed out of the front door, I walked to my bedroom, called Dean, and told him we needed to talk.

Dean cried.

He said he didn’t understand.

I said I didn’t either. But I was sure. It was what I had to do.

* * *

Five years after I broke up with Dean, I was still calling myself a slut—though it was no longer high school kisses that spurred my shame, but college attempts to have sex with my long-term boyfriend. Now twenty-one, I had left my religious community, having determined that I was incapable of being the woman they made it clear I needed to be in order to belong. I had changed my mind about attending Bible college and begun attending a secular liberal arts college outside of New York City.

Yet, when the lights were turned low, it was as though nothing had changed. The closer I got to losing my virginity, the more likely it was that the word slut would run through my mind on ticker tape. Eventually, I’d find myself in a tearful heap in the corner of my boyfriend’s dorm room bed, tormented by the same fear and anxiety that had driven me to break up with Dean when I was sixteen.

I had left the evangelical church but its messages about sex and gender still whirred within my body. Even after I calmed myself down and apologetically kissed my boyfriend goodbye, I couldn’t let go of the lingering fear that we had gotten too close to having sex this time, that I had gotten pregnant, and that my sexual sins would soon be exposed to the religious community I’d left but still desperately wanted to approve of me. Eventually, I’d walk to the local drugstore and buy a pregnancy test. I was still a virgin, but taking the test was the only way I could steady my breathing.

Until the next time.

I searched for books, articles, and online communities that might help me understand what I was experiencing. And when I was unable to find any, I called up first one, then two, then several of my childhood girlfriends from my former church youth group. I told them what was happening to me, and then, I sat in stunned silence as they told me they were experiencing many of the same things. The relief I felt knowing I was not alone sustained me, but my struggles continued. Until, at the age of twenty-six, I quit my job, drove across the country to my midwestern hometown, and set out to find the others.

I sat down at my parents’ kitchen table and paged through old church directories. One by one, I called the families of girls who I thought might still live in town: Hi, I don’t know if you remember me but I went to youth group with your daughter . . . Linda Kay Klein . . . Right, right! . . . It’s nice to hear your voice too . . . Yeah absolutely . . . You know, I haven’t talked with your daughter in so long, do you think I could get her number or email address from you?

I spent a year meeting with childhood friends. Some were single; others were married; some had had sex before marriage; others had waited to have their first kiss at the altar; some were still evangelical; others were decidedly not. Yet in many of their whispered stories, I heard themes I recognized from my own life—fear, anxiety, shame.

That year, I began to piece together an epidemic that I have not been able to turn away from since: evangelical Christianity’s sexual purity movement is traumatizing many girls and maturing women haunted by sexual and gender-based anxiety, fear, and physical experiences that sometimes mimic the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Based on our nightmares, panic attacks, and paranoia, one might think that my childhood friends and I had been to war. And in fact, we had. We went to war with ourselves, our own bodies, and our own sexual natures, all under the strict commandment of the church.

This was the beginning of a twelve-year journey. In these years, I earned an interdisciplinary master’s degree for which I wrote a thesis focused on white American evangelicalism’s gender and sexuality messaging for girls; I worked alongside inspiring gender justice warriors to create change within the world’s major religions; and I connected with hundreds of evangelicals and former evangelicals from across the country and talked with them about the impact that the purity movement had on their adult lives.

* * *

“So, freshman year of high school, sex ed. The PE coach decides to do abstinence education,” Renee told me, sitting cross-legged on the couch in her college apartment, where she was telling me about her upbringing in the South. I moved my recorder closer to her to be sure I was capturing her voice. “She said, ‘Who wants this Oreo?’?” Renee continued. “Everybody raised their hand. Then she passed it around the class and had everyone spit on it, or drop it on the ground, and when it got back to the front of class it was disgusting.

“Then she said, ‘Okay. Now, who wants this Oreo?’ No one raised their hand.

“It was an analogy for: ‘If you’re sexually promiscuous, no one will want you.’?”

I have heard many stories about object lessons like this one being taught in churches, community-based organizations, and public schools like Renee’s. One object lesson uses a car metaphor: virgins are described as a shiny new car that everyone wants to buy, and all those who have had sex are described as used cars that nobody wants (having gotten stained, rusty, and more and more broken down with every “ride”).IV Another uses a tape metaphor: virgins are described as a new piece of tape that can easily bind to things (a virgin woman capable of emotionally binding with her husband), but that picks up more dust and dirt each time that it is stuck to something new until it is too dirty to stick to anything (or anyone) anymore. Then there is the unused tissue versus the “used” tissue full of snot, mucus, and phlegm, which is said to represent a girl or woman who has had sex; the clear glass of water versus the one to which food coloring has been added (the tiniest drop changing it forever); and the seemingly endless iterations on food: the untouched cookie or candy bar versus the one that has been chomped into; the unwrapped lollipop versus one that decreases in size and desirability after being licked for the first time, just once, and then licked again by anyone who is willing to put somebody else’s saliva in their mouth; the new piece of gum versus the one that has been chewed; and so on.

Though shaming language is embedded into sexuality messaging for both boys and girls, it is especially intense and embodied when delivered to girls. In fact, the only one of the aforementioned metaphors that I have personally heard applied to both males and females is the tape metaphor.

Though Renee was “relatively innocent” sexually, in her words, she told me the lesson made even her limited sexual experience feel life-defining. “?‘Well I’m spoiled now,’?” she reasoned, looking at the disgusting Oreo no one wanted. “?‘So I may as well do whatever.’ It was really damaging to my development.”

“It’s interesting,” I replied to Renee. “The emphasis on being devoured, right? This message that we should look at our sexuality as food—”

“For someone else,” Renee finished my sentence.

I nodded. “As though it’s all about how well we are able to feed others,” I continued. “Like, ‘If I let this person eat, then this other person won’t be properly fed. Or won’t want to devour me—’?”

“Or ‘I just won’t be any good anymore,’?” Renee added, frowning.

The purity message nestles neatly into the larger “us” versus “them” messaging I was raised with in the church. Those on the “positive” side of the binary are said to have access to God, Heaven, the community, and a happy life as one of “us.” Those on the “negative” side of the binary are said to be isolated from God, alone, and headed for Hell, a place of suffering reserved explicitly for “them.” Though one’s place on that binary is technically supposed to be determined by one’s belief system, let’s face it—you can’t see into another person’s heart and know whether she really believes these things or has just memorized a bunch of talking points. So if you want to assess who’s really a Christian and who’s not—and lots of people do—you need a proxy, some externally measurable quality that is deemed representative of the person’s internal commitment. Among single people in the church, one of the most popular proxies is sex. The celibacy represented by a purity ringV—real or metaphorical—identifies evangelicals as one of “us.” This may never be spoken, but as a girl in the subculture, I can assure you, it is felt.

Growing up, I heard a lot of talk about how evangelical Christians were better people than secular or other religious people (funnily enough, I now hear the exact same self-congratulatory messages from secular liberal people). But the truth was, I couldn’t always tell the difference between a Christian and a non-Christian. I saw both lie, both steal, both love, and both unselfishly give to others. But one tangible thing we could point to as evangelicals was that we didn’t have sex before marriage. There was that. There was always that. Which is why, I believe, the threat of losing that so-called sexual purity seemed so grave. Were we to have sex outside of marriage, could we even call ourselves Christians anymore? What if we made out? Kissed? Held hands? Had a crush? How close to sex could we come before we were no longer Christians?

“Sex is the big issue that for some reason marks your spiritual standing with God,” Renee illustrated. “Like Jessica Simpson. People considered her a Christian because she waited to have sex until marriage. That was her whole marker of faith in God. And every testimonyVI you hear from someone, they have to mention the sexual sins of their past. They might not mention the fact that they . . . I don’t know . . . got rid of their shopping addiction, but they mention the fact that they got rid of their addiction to porn. It’s like, ‘. . . and then I stopped sleeping around. I became a Christian and I stopped sleeping around.’?”

After all, what other sin is said to fundamentally change you forever? You can be born again and have your slate wiped clean of lying, stealing, even murder. And if you do these things again later but honestly apologize to God, your sin is again forgiven. But sex outside of marriage is the only “sin” that I have ever heard described as changing you. Before sex, you are a virgin. After sex, well . . .VII

I remember there was this girl’s high school retreat where the leader was talking about purity and how important it was and how she felt disgusting. Basically, she started breaking down crying because she hadn’t stayed pure, and this happened all the time in my church. My youth pastor’s wife, she had walked down the aisle pregnant and now they are married and she has two boys, but she would still weep about it. Not that the youth pastor who she had the baby with is weeping about it! But his wife still weeps about it and says how she feels ashamed, disgusting, and wrong twelve years later. (Muriel)

Sometimes one doesn’t even need to have sex to feel this way. The purity movement teaches that every sexual activity—from masturbation to kissing if it elicits that special feeling—can make one less pure.

What does it even mean to be “pure”? The lines were so blurred, and there was so much tragedy tied up with it: “Don’t do this, because if you do this you’re ruining your relationship with your future spouse . . .” “Don’t just be pure in body; you need to be pure in spirit . . .” Everything was just so intertwined with each other. It almost seemed like if you weren’t being physically impure, you were being spiritually and emotionally impure. Being “pure” became this really heavy, heavy weight to bear all the time. It almost made me go crazy questioning, “Well, is this impure? . . . Is this wrong? . . . Is this okay? . . . Is this going on?” (Holly)

Some purity movement advocates even teach that sexual thoughts and feelings can make one impure.

I sort of thought of being naked with a guy. I didn’t picture him naked. I didn’t picture me naked. I just sort of imagined, “I could marry him and be naked with him one day.” And I felt terribly guilty over that for a long time. (Rosemary)

And it is implied that the sexual thoughts, feelings, and actions of others can be signs of your impurity as well (because surely you did something to make them think, feel, or do what they did).

I had one half-kiss at the age of sixteen that made me brush my teeth for ten minutes afterward.VIII It wasn’t even a kiss. He kissed me but I did not kiss him back. I think I mostly just stood there, kind of horrified and fascinated at the same time. But I felt guilty, ashamed, dirty for years. How screwed up is that? I thought I was dirty and ruined, a soiled package. But you know how it is. They say, “Make sure you don’t have to tell your husband the high number of people you’ve kissed someday. Your first kiss should come from your husband.” And I had just ruined it. I ruined it by letting this happen. [But didn’t you say you didn’t kiss him back?] Yes, but I felt I let it happen. I didn’t read the signals. I wasn’t on my guard. We jump through hoops to make it about our shamefulness. (Jo)

The purity message is not about sex. Rather, it is about us: who we are, who we are expected to be, and who it is said we will become if we fail to meet those expectations.

This is the language of shame.

Shame is the feeling “I am—or somebody else will think I am—bad” (as opposed to guilt, for example, which is associated with the feeling “I did something bad”). The religious purity messages many of us received as girls were not about what we might do, but about what we would be, or be seen as. Of course, we are all different and therefore respond to shaming of this kind differently. Our family dynamics, the affirmation we receive (or don’t receive) for other aspects of ourselves, the intersecting messages we are given about who we are based on our race, our ethnicity, our socioeconomic status, our physical and mental health, and so on all have roles to play. But the conversations that I have been having over the past twelve years make it clear that the influence of the consistent shaming embedded into the religious purity message, particularly during stages of extreme neural plasticity such as adolescence is for sexual development, can be extreme for many.

After all, researchers have found that our brains bend toward whatever it is that our attention is directed to.3 It follows that if an adolescent is regularly given shaming messages—like the purity message that a girl or woman is utterly and fundamentally pure or impure, good or bad, pleasing or displeasing, desirable or undesirable, et cetera, based on her sexual expressions or lack thereof—she will become more likely to experience shame in association with sex than she otherwise may have been. As psychiatrist Dr. Curt Thompson explains in his book The Soul of Shame: Retelling the Stories We Believe About Ourselves, “With repeated exposure to events [in which we feel shame], we pay attention to and, via our early neuroplastic flexibility, more permanently encode these shame networks. Thus, they become more easily able to fire later on, even when activated by the most minor or even unrelated stimuli.”4

This is not good news for the shamed individual, or their potential partners. Shame tends to make people feel powerless and even worthless. It creates a fear of abandonment that, ironically, makes us push others away. We want to hide those aspects of ourselves we are ashamed of, so we may emotionally withdraw from those close to us, lash out at them to keep them at bay, or isolate ourselves in self-blame. Whatever it takes to keep the world (including ourselves) away from those parts of us that we have come to believe make us bad.

Over the years, shame adds up, but it can happen so slowly we don’t even notice it. We may look at each shaming incident one at a time and tell ourselves that what was said or done to us wasn’t that bad. In time, we become less and less sure that we can, or should, heal. Rather than seek help, we bury our shaming experiences deep in our bodies, where they are held similarly to trauma.

Shame researcher Dr. Brené Brown explains this phenomenon in her book I Thought It Was Just Me (But It Isn’t): Making the Journey from “What Will People Think” to “I Am Enough.” She references the work of Harvard-trained psychiatrist Dr. Shelley Uram, who calls attention to the importance of recognizing “small, quiet traumas” which she has found “often trigger the same brain-survival reaction” as larger traumas, such as a car crash. In I Thought It Was Just Me (But It Isn’t), she writes:

After studying Dr. Uram’s work, I believe it’s possible that many of our early shame experiences, especially with our parents and caregivers, were stored in our brains as traumas. This is why we often have such painful bodily reactions when we feel criticized, ridiculed, rejected, and shamed. Dr. Uram explains that the brain does not differentiate between overt or big trauma and covert or small, quiet trauma—it just registers the event as “a threat we can’t control.”5

Perhaps this explains why I have heard so many stories of PTSD-like experiences in association with people’s sexuality, their bodies, and the church.

Today when I go into a church, I can’t stop panicking. I feel like I am going into a place in which I was raped, though I wasn’t. It is light-years easier for me to talk about being sexually abused as a child—I could give a public lecture about that—than it is for me to talk about what that religious community did to me. Sexual abuse is something that happened to me, but this was at the core of my identity. I participated in the community’s messaging about who I was, and allowed it to define me for years. The fear, the obsessing, the anxiety. It’s torment. It is Hell. It felt like torture. (Nicoletta)

And yet, the impact that shaming can have on people’s lives generally goes unacknowledged and sometimes even unnoticed within the communities in which it most regularly occurs. In some cases, shaming is so common it is coiled around core beliefs, laced through theology, and twisted into doctrine, making it nearly impossible to see.

I’m trained as a therapist, and I didn’t even recognize the trauma that I had in my life around religion until a few years ago. I’ve never spoken about these things with anyone else, not even with my closest friends. I have been through years of therapy and I’ve never once mentioned it to a therapist. (Nicoletta)

Shame can become like the smell of our own homes. The hum of an air conditioner. The feel of a wedding ring. It’s just . . . there. Which is when it is most dangerous. Because it is then that we are most likely to dismiss, rather than deal with, its dangerous effects.

I can’t tell you how many people are experiencing the kinds of things that my interviewees and I have and do. But the regularity with which I am approached and asked if I will talk to someone, or someone’s friend, or someone’s partner about the way in which religiously rooted sexual shame is impacting their lives makes one thing clear: It’s enough people that we need to be talking about it.

* * *

“So, what exactly is an evangelical?” I’m asked by non-evangelicals and evangelicals alike. After all, most evangelicals simply call themselves Christians. By which they mean real Christians (as opposed to those who think they are Christians but have got it all wrong, like non-evangelical Catholics and mainline Protestants).

Evangelical Christianity is a very new religious expression, though it has roots in older forms of Christian faith. It was just 1948 when a group of largely conservative individuals calling themselves the new evangelicals branched away from various Protestant groupsIX to form the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE).6 And it wasn’t until the 1990s that evangelical Christianity became the political and cultural force we know it as today.

Some say the word evangelical comes from the Greek euangelion, which translates to “good news.” Evangelicals define the Good News as Jesus’s death and resurrection, which allows sinful people to enter Heaven. Most believe a person must be “born again” to receive this salvation (so many, in fact, that the Pew Research Center considers people evangelical if they report either being “evangelical” or “born again”).X An individual’s born-again experience can happen during a group altar call,XI or sitting alone in one’s living room the day one decides to give up trying to do things one’s own way and start trying to do them God’s way. However one is born again, afterward, he or she is expected to spread the Good News to others—that is, to evangelize. Evangelicals are often further distinguished by their theological and moral conservatism, biblical literalism, emphasis on personal piety, conservative political positions, and engagement with technology, popular culture, and capitalism. But I can personally think of exceptions to every single one of these definitional rules.

Even the core tenets of evangelicalism around believing in, and evangelizing about, the Good News are often defined, and engaged with, differently by various individual evangelicals. As an illustration of the diversity among evangelicals, one evangelical woman recently told me that an evangelical must have three things: “First, intimacy with Jesus, which looks different for everyone. For example, my brother can have a beer with Jesus, whereas I wrestle and beg and devote time to biblical study. Second, trying to be like Jesus, which leads some people to vote Republican and others to vote Democrat depending on how they read who Jesus is and what he stands for and against. And third, promoting the Good News, which, when I was young, I understood to mean getting born-again decisions for Jesus, but today I consider to be about spreading loving, forgiveness, and acceptance.”

In 1995, former president of Auburn Theological Seminary Barbara Wheeler said the best definition of an evangelical may be “someone who understands its argot, knows where to buy posters with Bible verses on them, and recognizes names like James DobsonXII and Frank Peretti.”XIII7 Her references are a bit dated, but her point is right on: evangelicalism is best thought of as a subculture. By this definition, a churchgoing Catholic who reads a lot of evangelical books, listens to an evangelical Christian radio station, and has a close circle of evangelical friends is more “evangelical” than the unengaged individual who occasionally attends an evangelical church, but is otherwise disconnected from the community. After all, you only get the real stuff of evangelicalism—the feelings, the fervor—by being in the room.

The evangelical subculture is diverse, decentralized, and constantly changing. After all, evangelical Christianity is the single largest religious grouping in the United States. More than a quarter of Americans belong to it, and more than a third of American adolescents do.8 Within the United States, some evangelical communities are predominantly white, some African American, some Asian American, some Hispanic, some more mixed, and so on. Some evangelical communities are charismatic, some fundamentalist, and some Pentecostal. Some are conservative, some moderate, and a smaller number progressive. When I use the term evangelical in this book, I am, unless otherwise noted, referring to the largest evangelical grouping—the white, conservative, American evangelical Christian subculture within which I was raised.

Within evangelicalism there are several denominations, like the Assemblies of God and the Southern Baptist Convention, but Mennonites, Holiness groups, and Dutch Reformed groups are also generally considered evangelical, as are many nondenominational church groups, such as the Christian and Missionary Alliance and the Acts 29 Network. Most nondenominational evangelical (and an increasing number of other) churches brand themselves independently, taking on inspiring names like New Life Church, or naming themselves plainly—for example, taking the name of the city or neighborhood in which they are based and adding the word church to it. There are also many evangelical house churches, missional communities, and experimental church groups, not to mention Catholic and mainline Protestant churches and groups that self-identify as evangelical.

Unlike other forms of Christianity, evangelicalism lacks a traditional hierarchy, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t rules within it. The rules are simply translated—as they are in any subculture—through a culture of cool (or “moral” or “pure” or “Bible-believing”) and disseminated through pop culture: celebrities, books, music, events, speakers, et cetera. Still, evangelical institutions—by which I mean colleges, publishing houses, music production houses, and so on—and organizing bodies like the NAE are anything but obsolete. When the subculture expands, evolves, or in some other way threatens to transform itself, as it has many times in its short history, these institutional forces often step in—declaring a former evangelical rock star who is pushing the boundaries of the belief system to be a heretic, or firing evangelical professors who too boldly challenge its conservative core. And because every kind of evangelical belief (spiritual, religious, political, and cultural) goes by the same name—Christian, a loaded term that defines whether or not you are going to Heaven—people’s beliefs about your salvation sometimes depends on institutional leaders’ assessments of your opinions on things that many would argue should have nothing to do with religion, like who you vote for. Those are high stakes for an evangelical who is considering going against the subculture’s dominant stance.

Within all of this diversity, the sexual purity message is one of the most consistent elements of the evangelical subculture. Among my interviewees, a remarkably similar language and set of stories about gender and sexuality surfaced. The same adages, metaphors, and stories from books, speakers, and events were described to me over and over again, though those I spoke with grew up around the country and in some cases the world.

As Donna Freitas writes in her study of college students’ spiritual and sexual lives, Sex and the Soul: Juggling Sexuality, Spirituality, Romance, and Religion on America’s College Campuses, this creates a very consistent set of sexual attitudes among young adults who grew up in the purity movement.

Though the evangelical students I interviewed broke almost every liberal preconception about them, proving to be diverse in their politics, nuanced in their expressions and beliefs about Christianity, and perfectly willing to swim in a sea of doubt and life’s gray areas, their pursuit of purity is the one area where almost all of them could see only black and white. Falling short of ideal purity can jeopardize not only a young adult’s standing among her peers but also, as these young adults are taught through purity culture, her relationship with God.9

Overtly shaming messages, like the object lessons that I mentioned earlier, are easiest to identify. But the more powerful, and far more prevalent, messages are covert: shaming attitudes embedded into everyday language, shaming lessons slipped into stories, shaming treatment felt by those who are being shamed and observed by those who fear they will be shamed next. Sometimes, you can be in the room when these covert messages are relayed and not even hear them. They are that commonplace. If the messages don’t hurt you, you are less likely to hear them (for instance, a straight person is less likely to hear a covert homophobic message than a queer person is). And if the messages benefit you, you are even less likely to hear them (for instance, a husband whose pastor turns to him and asks if he can hug the man’s wife may not “hear” the pastor subtly referring to his wife as his property . . . but she might).10

* * *

Purity preaching is not new, nor is it exclusive to evangelical Christianity, but evangelicals have played—and continue to play—an important role in bringing this message to the mainstream. After the sexual revolution, Americans were scared. AIDS was killing people by the thousands, there were growing concerns about other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and many conservatives believed a return to traditional values, including chastity, was the only solution. Spurred by this perspective, federal money for abstinence-only-until-marriage education began to flow—first under Reagan,XIV then more under Clinton,XV then still more under Bush.XVI11 This influx of government money catalyzed the purity industry.

According to the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS), over $2 billion in federal funding has been allocated for abstinence-only programs in the United States since 1981.12 Much of this funding came through the Title V abstinence-only-until-marriage program, which is still in place today. This program requires states to match every four federal dollars they receive with three state-raised dollars, presumably increasing the state-level contributions made toward abstinence-only programming in the process as well. The money is then redistributed to community-based organizations, faith-based organizations, local and/or state health departments, and schools. Every state but one (California) has at one time accepted Title V federal funding for abstinence-only-until-marriage programming.13

With money like this just waiting to be spent, purity purveyors previously focused on small religious audiences moved into the mainstream marketplace, selling events, speakers, and curricula. This is when we began to see purity-themed rings,XVII bracelets, necklaces, shirts, hats, underwear, books, journals, devotionals, magazines, Bible studies, trainings, guides, DVDs, planners, and other products. I have come across purity-themed, posters, coffee mugs, key chains, buttons, stickers, water bottles, mints (on which the words “sex is mint for marriage” are printed), and have even read references to purity-themed lollipops (which I assume are sold to remind people of the lollipop object lesson in which every sexual experience is compared to a lick on the lollipop of one’s life, making them less and less attractive to potential suitors who would prefer an unlicked and unwrapped lollipop for their sole consumption). It is nearly impossible to assess who purchased each of these products and with what money, but the government certainly wasn’t the only buyer. Many of these products were ultimately bought by the audience for whom they were originally intended—evangelical Christians. As Doug Pagitt, pastor of the progressive evangelical church Solomon’s Porch, explained: “When it came to sex, churches had gotten quiet. Too quiet. We wanted resources. We needed resources. So when someone made them, we used them.”14

Within the evangelical Christian subculture, the purity industry gave many adolescents the impression that sexual abstinence before marriage was the way for them to live out their faith. This is perhaps best illustrated by the production of purity-themed Bibles. The Abstinence Study Bible produced by the Christian group Silver Ring Thing, for example, includes sixty pages of non-biblical material such as dating advice like “avoid the horizontal” and “keep your clothes on, in, zipped and buttoned.”15 When about one-sixth of an adolescent’s Bible is marketing about the importance of abstinence, how could she not reach the conclusion that her sexual thoughts, feelings, and choices determine her spiritual standing?

Products like these integrate purity messaging into a young person’s daily life. Imagine a seventh-grade girl arriving at her middle school on a snowy day. She takes her mittens off and her attention is caught by the sparkling ring that she has promised to wear until the day she gives the gift of her virginity to her husband. This, she recalls being told, will ensure your husband will never leave you. But if you ever break your promise . . . An eighth-grade girl kisses a boy for the first time. Skipping home on a high, she is sure the sky has never been so blue or the light quite so clear. Approaching her front door, she pulls out her keys, noticing her purity-themed key chain. She stops in her tracks. Will my husband be upset when he finds out my first kiss wasn’t with him? she asks herself, her anxiety rising. A ninth-grade girl brushes her teeth in front of the bathroom mirror where she has taped her copy of the purity pledge she signed at a rally. (The other copy of the contract was sent to the True Love Waits headquarters.) Her youth pastor had suggested she put the contract somewhere she would see it every day, especially since she started dating Mike.

When products are purchased using government money, the teachings are supposed to be non-religious, but sometimes, things get messy. The group called the Silver Ring Thing, launched in 1993, offers an example. They received $1.4 million in federal funding.16 In 2005, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit contending that the Silver Ring Thing was evangelizing at its government-funded events. A settlement was reached and the government stopped funding the Silver Ring Thing in its current form.17 Now solely supported by private money, the Silver Ring Thing’s events, which continue to be offered to this day, culminate in an invitation for adolescents to sign a purity pledge and give their life to Christ at essentially the same time, again connecting the concepts of salvation and sexual purity.18 The Silver Ring Thing reports having hosted nearly 1,300 of these events and having reached more than 684,000 people.19

Also launched in 1993, this time by the Southern Baptist Convention, True Love Waits is generally considered the most powerful player in the purity industry. True Love Waits never received federal funding, but its relationship with the government was robust nonetheless. True Love Waits actively campaigned the government to allocate money to abstinence-only-until-marriage programming and, a year after its launch, startled the country by bringing 20,000 adolescents to the National Mall, where they staked 211,156 signed purity pledges on the lawn. Afterward, 150 purity activists had a special session with President Bill Clinton.XVIII Two years later, Congress allocated $50 million a year for the aforementioned Title V abstinence-only programming.

It’s hard to estimate just how many young people have been impacted by the purity industry, but one purity curriculum provider approved for federal financial support boasts on its website of having reached over 4 million students in forty-seven states.20 That’s about 10 percent of the total number of ten- to nineteen-year-olds living in the United States and its territories today!XIX If that many young people have been reached by just this one curriculum, we can only begin to imagine how many have been reached by the vast array of other products.

In 2008, federal funding for abstinence-only-until-marriage programming was curbed under the Obama administration after a congressionally mandated, comprehensive nine-year study showed that students who experienced abstinence-only education in public schools were “no more likely than control group youth to have abstained from sex and, among those who reported having had sex, they had similar numbers of partners and had initiated sex at the same mean age.”22

But the purity industry may be making a comeback.

Dedicated federal abstinence-only-until-marriage funding meaningfully increased again in 2016, bringing the total federal funding to $90 million for 2017.23

But this time, even evangelicals don’t seem so excited about that, at least not those that are working on the ground.

“It made youth workers feel like they were doing good work because they were talking about these taboo issues like sex that the church never talked about before and that needed to be talked about,” said Pastor Doug Pagitt—who I cited previously—about the purity messaging. “Then, after a few decades, people were like, ‘Oh. This stuff is bad.’?”

“Progressive evangelicals realized that?” I clarified. “Or mainstream evangelicals?”

“Across evangelicalism. Not just progressives.”

“So where is mainstream evangelical sexuality education today?” I asked him.

“It’s in huge flux. It’s a changing landscape. Everyone is confused.”

“So, it’s a moment of ‘not that . . . but now what?’?”

“Yes,” he answered definitively.24

* * *

Not every adolescent who consumes purity messaging will have the same experience. It’s one thing to receive a shaming message at a public school assembly while your friends snicker, and quite another to receive it from inside a closed community where the messages are deeply revered by all. As Dr. Curt Thompson writes: “When I perceive that I am receiving the shame from a community of voices, the pain can become unbearable. When the collection of the voices of an entire community shames us, it is more unwieldy due to our inability to locate it centrally in any one place. And so when I feel shame in my family or my church, addressing it feels quite overwhelming.”25

Perhaps this explains why the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health found that evangelical adolescents are more likely than their peers to expect that if they have sex, it will both upset their mother and cost them the respect of their partner. Evangelical adolescents are also among the least likely to expect sex to be pleasurable, and among the most likely to expect that having sex will make them feel guilty.26 Yet one’s level of religiosity (there is a 30 percentage point gap in anticipated sexual guilt between the least and the most religious youth)27 and one’s gender (girls are a whopping 92 percent more likely to experience sexual guilt than boys)28 have even greater impacts on one’s likelihood to experience sexual shame than one’s denominational affiliation. Considering my interviewees and I were all at one time 1) highly religious, 2) evangelical, 3) girls, it is likely that our reactions to the purity movement’s messaging is in some cases more extreme than those of individuals outside our demographic might be. Yet our stories illustrate intensified versions of experiences I believe almost all women and many others have had.

Right now, groundbreaking research is being performed among young adults raised in three conservative Christian communities—Baptist, Catholic, and Latter-day Saints. This research that reiterates many of the previously mentioned findings and posits several new ones that can help us better understand just how and why purity messaging is impacting girls. The researchers write in their brief:

There is little support indicating that the mechanisms currently used in our society (abstinence education, chastity pledges, and religious grounding) to curb teenage sexual activity actually work. The question remains, “Is our focus on sexual abstinence doing anything?”

It turns out that those who are sexually active and have experienced abstinence education and/or have stronger beliefs that the Bible should be literally translated [a core tenet of evangelicalism], have more sexual guilt.XX . . . females report significantly higher sex guilt than males (and) sex guilt from the first sexual experience is predictive of higher sex anxiety, lower sexual efficacy, and lower sexual satisfaction. So, females, in particular, who have strong religious beliefs and are engaging in premarital sex, are having unsatisfactory sex, they have high anxiety about it, and don’t feel that they are capable of changing their situation.

Lastly, the relationship between sex guilt and sex anxiety, sexual efficacy, and sexual satisfaction, doesn’t diminish over time; it gets stronger.XXI . . . This is not a recipe for young women to embark on a fulfilling relationship with their partner and we predict could be an indicator of further sexual problems and relationship issues.29

To summarize, first, the researchers are finding that purity teachings do not meaningfully delay sex. Second, they are finding that they do increase shame, especially among females. And third, they report that this increased shame is leading to higher levels of sexual anxiety, lower levels of sexual pleasure, and the feeling among those experiencing shame that they are stuck feeling this way forever. Oh, and it doesn’t get better with time . . . it gets worse!

Yep. Sounds about right.

* * *

I have seen the Bible used against people many times. For some of those I’ve spoken with, it is the literature of their trauma and I feel no need to redeem it for these individuals. But I take comfort in knowing that when I read the Bible today, I find more liberation in its pages than I was taught to see in it growing up. Take stumbling blocks. Interestingly, the verse most purity preachers point to when accusing girls and women of being stumbling blocks isn’t the one about sexuality that I referenced earlier. It’s a verse about food. In Romans 14, Paul suggests that his readers not eat unclean food in front of those they think it will distress: “Let us then pursue what makes for peace and for mutual upbuilding. Do not, for the sake of food, destroy the work of God. Everything is indeed clean, but it is wrong for you to make others fall by what you eat; it is good not to eat meat or drink wine or do anything that makes your brother or sister stumble.”30

Those who call women and girls stumbling blocks interpret Romans 14 as a metaphor: Girls and women are technically free to dress how they want, just as we are all free to eat what we want, but if girls and women care for their brothers, they should dress and behave modestly so they don’t become stumbling blocks to them.

But look a little earlier in the chapter and it becomes clear that Paul’s larger point is that we should spend less time judging others’ choices as right or wrong—arguing that a multiplicity of choices can honor the Lord depending on the heart of the individual—and that we should spend more time loving one another:

Those who eat must not despise those who abstain, and those who abstain must not pass judgment on those who eat; for God has welcomed them. Who are you to pass judgment on servants of another? It is before their own lord that they stand or fall. And they will be upheld, for the Lord is able to make them stand. Some judge one day to be better than another, while others judge all days alike. Let all be fully convinced in their own minds. Those who observe the day, observe it in honor of the Lord. Also those who eat, eat in honor of the Lord, since they give thanks to God; while those who abstain, abstain in the honor of the Lord and give thanks to God.31 . . . Why do you pass judgment on your brother or sister? Or you, why do you despise your brother or sister? For we will all stand before the judgment seat of God.32 . . . So then, each of us will be accountable to God. Let us therefore no longer pass judgment on one another, but resolve instead never to put a stumbling block or hindrance in the way of another.33

I don’t know about you, but within the larger context of the chapter, it seems to me that judgmentalism is the stumbling block Paul is most concerned with here, not modesty. Reading these verses as an adult I cannot help but shake my head—the whole time my childhood friends and I were being told that we were stumbling blocks, our accusers were, even then, placing the real stumbling blocks before us: purity-based shaming and judgmentalism that pushed many of us right out of the church.

* * *

This book is divided into four sections. The first section describes four purity culture stumbling blocks for girls. These stumbling blocks are: 1) the accusation that if purity culture doesn’t work for you, it’s you (not its teachings) that are the problem; 2) the requirement that all girls and women must perform a stereotypical gender role to be acceptable; 3) the expectation that all unmarried girls and women must maintain a sexless body, mind, and heart to be “pure”; and 4) the systematic mishandling of sexual abuse cases and survivors.XXII The second and third sections of the book delve into the challenges these stumbling blocks pose to girls as they become adults inside, and outside, of the church, respectively, and the ways they find to break free from the purity message in both places. The fourth section of the book explores how individuals raised in the purity movement are personally hurdling these stumbling blocks and charting new pathways for those who come after them. Each of these four sections opens with a chapter highlighting a story from my own life. Chapters that follow feature the stories of my interviewees.

The individuals whose stories are shared in this book are between their early twenties and their early forties, having been raised as evangelical Christian girls sometime between the late 1980s and the early 2000s. Many, but not all, grew up in my hometown, where my interviews began. Most are using pseudonyms and, unless otherwise noted, all are white Americans.

When I started interviewing people twelve years ago, it felt important not to muddle all of the racially and ethnically distinct evangelical subcultures together in an attempt to “speak for all” when—as a white woman aware that her race and ethnicity protects her from other forms of oppression that intersect with the purity message—I can really only speak for one. So, I stuck to collecting the stories of white American evangelical girls, like me, as they grew up. Yet over the years, I have faced the reality that the purity industry has impacted many more people’s lives. I have heard stories similar to mine and those of my interviewees from many outside of our demographic. From Catholics, mainline Protestants, Jews, Muslims, and many with no religion at all. From African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans, and other Americans of color. From people around the world. And from men. Lots and lots of men.

As recent conversations spurred by #MeTooXXIII and #ChurchTooXXIV have made plain, the evangelical Christian church is not alone in shaming and silencing women and others. As such, I expect the stories in this book will be unfortunately familiar to many.

For more information about the individuals featured in this book, please see page 291.

* * *

Some of my critics will say, “I grew up in purity culture, and had a great experience.” I wouldn’t want those for whom this is true to change a thing about their lives. Except, that is, the belief some hold that because purity culture worked for them, it ought to work for everyone.

Other of my critics will point to people raised in the purity movement who do not represent its messaging in adulthood, arguing that the movement obviously didn’t impact them. “I can think of half-a-dozen women off the top of my head who are evangelical, but whose lives do not fit the purity model,” one evangelical man informed me, for example. “I can’t imagine that these women are experiencing or ever have experienced the things you are talking about,” he added with finality. I wonder if this man has ever taken the time to ask these half-a-dozen women about the impact the purity movement did or did not have on their development. I urge us all to consider that everyone around us is dealing with things they are not showing to us. Some may have never been asked about their shame; some may be making the choice not to share about it even when they are asked about it; and others may experience shame so regularly that they don’t even notice it . . . but that doesn’t mean it isn’t there.

Still more of my critics will say, “You turned out alright. You’re happily married with a great family. You’re a strong Christian (even if you’re not an evangelical). Whether or not you liked the purity message, it appears to have been good for you.” Though evangelicalism offered me many gifts—a deep spiritual life, mentors I could rely on, leadership opportunities that boosted my confidence, and more—the purity message was not one of them. Intended to make me more “pure,” all this message did was make me more ashamed of my inevitable “impurities.”

* * *

When I was young, I thought God was in the hand that scooped me up when I joined the evangelical church. The hand cradled me, and I felt safe and protected. I believed that God lived here, in this one religious expression with all of its interpretations, rules, and regulations, including those that felt wrong to me even then, like the purity ethic.

But as I grew older, the hand began to squeeze me, and I became uncomfortable. I tried to make myself smaller, squishing myself down so I could fit inside of it, but all of the ways in which I was not the “right” kind of Christian woman squeezed through between the hand’s fingers and I was exposed. I tried cutting parts of me off, the appendages that made it more difficult to fit, but I didn’t have the guts to really cut them off. I just hid them under my clothing, like a character in a B movie hiding an arm inside her shirt and pretending the dangling sleeve means it isn’t there. Finally, I decided I’d try to stretch out, make myself some room. Maybe, I thought, the hand will loosen a little in response. But instead, the hand tightened its grip. More and more of me came oozing out between its fingers until one day I came bulging out between its thumb and its pointer finger like a giant bubble, and with a plop, I dropped. Fell from grace. And landed flat on my face.

I remember how I felt. Scared and alone. Lying there trembling on the floor while looking up at the hand that once held me. I had lost so much—my community, my purpose in life, and worst of all, God, whom I missed so badly my body ached. I looked up at the hand sometimes, and wished that I was there so I could touch God again. But I didn’t feel I was allowed to.

Eventually, I gathered up my broken body. There on the floor, with no one paying attention to me, I uncovered those parts of me that I had tried to hide or make small. And I watched, amazed, as these parts of me unfurled—some gorgeous, some terrifying, and others plain. From time to time, I felt something I thought I had lost—a holy presence, the feeling someone was watching out for me. In time, I came to trust, to know, that God was still with me. That God was in the hand, yes. But also here . . . and here . . . and here. That no hand can confine something so great.

Today, I am a Christian, but I stand outside of the hand I grew up in. Waving to those in it and saying, “It is good in the hand. God is there. And s/he is also here. So let’s come together to end the shame that hurts all of us. For there is much work to be done.”

I.?Though I now see God as having no gender, I use masculine pronouns to refer to God in this book when the people themselves would have done so—as I certainly would have at this point in my life.

II.?The definition of this term depends on who you ask. Though historically a concert of prayer refers to a major prayer movement, in everyday Christian life it is often used in reference to group prayer organized around a specific purpose.

III.?In Totem and Taboo, Freud suggests that sometimes “a person may become permanently or temporarily taboo without having violated any taboos, for the simple reason that he is in a condition which has the property of inciting the forbidden desires of others and of awakening the ambivalent conflict in them.”2 This is what I experienced as an adolescent evangelical. I was taboo—guarded, and guarded against—long before I had ever done anything “wrong,” lest I awaken someone’s ambivalent conflict.

IV.?This object lesson also comes in a bicycle variety.

V.?A purity ring is a ring that a single person wears, often on their wedding finger, to remind themselves of, and communicate to others, their commitment to not having sex before marriage.

VI.?One’s testimony is the story of how they became a born-again Christian.

VII.?It should be noted that revirgination ceremonies (which I have personally only heard of being offered to and attended by women) are hosted by some churches. Though the idea of revirgination reflects the purity ethic that implies virgins are somehow “better” than non-virgins, and brings with it all the complications that come with that, I have heard these ceremonies described as healing experiences for some, particularly for those who have been raped or sexually abused.

VIII.?There is no definition for “half-kiss,” though it is a term I hear often in evangelical circles. One person might use it to refer to a peck or an otherwise short kiss, another to a kiss that she turned away from, etc. For many, the intention is to keep at least as many purity points as she deserves by not claiming a whole kiss when, for whatever reason, it didn’t really feel whole.

IX.?Fundamentalist Christianity was chief among these groups.

X.?However, a growing number of evangelicals are moving away from this emphasis on the born-again experience.

XI.?An altar call is an invitation for individuals to gather as a group and be led through a collective conversion or “born-again” experience. Generally (though not always), it takes place at the altar of a church.

XII.?The founder of Focus on the Family.

XIII.?A contemporary evangelical author.

XIV.?The Adolescent Family Life Act (FY 1982–FY 2010) was passed in 1981. Overall, AFLA received $209 million, a portion of which went to abstinence-only-until-marriage programs.

XV.?The Title V abstinence-only-until-marriage program (FY 1998–present) allocated $50 million per year in federal funds to states until FY 2015, at which point it went up to $75 million per year.

XVI.?The Community Based Abstinence Education (FY 2001–FY 2009) funding stream has allocated $733 million in federal funds for abstinence-only-until-marriage programming.

XVII.?Rings range in cost and quality and are often engraved with a Bible verse or personalized message. They are marketed to adolescents, parents, and groups that may be interested in bulk orders. Parents can even buy special purity rings for themselves, which are intended to remind them to pray for and daily encourage their kids’ sexual abstinence.

XVIII.?This effort was organized in conjunction with Youth for Christ’s DC ’94.

XIX.?According to US Census Bureau estimates, in 2015 there were over 41 million ten- to nineteen-year-olds in the United States and Puerto Rico Commonwealth and Municipios. It should be considered, however, that this curriculum’s reported numbers likely span the curriculum’s over-twenty-year lifespan, whereas the census estimates represent only one year.21

XX.?I was able to confirm with the lead researcher that what the research team calls sex guilt is the same as what I am in this book calling shame.

XXI.?The researchers later clarified that this doesn’t mean that the guilt gets more intense over time, but that the relationship between guilt and sexual anxiety, sexual efficacy, and sexual satisfaction is stronger for guilt more recently felt than guilt remembered from the first sexual experience. In this study, participants reflected on past feelings; longitudinal data was not collected.

XXII.?Please be aware that stories of rape, intimate partner violence, and incest do appear in this book.

XXIII.?The Me Too movement was founded in 2006 by Tarana Burke to support and unify sexual violence survivors, particularly women of color in underprivileged communities. In 2017, actor Alyssa Milano encouraged her Twitter followers to use the hashtag #MeToo if they had personally experienced sexual harassment and/or assault. The hashtag went viral.34

XXIV.?#ChurchToo was founded by poet Emily Joy and writer and religious trauma researcher Hannah Paasch. Many women—and men—used the #ChurchToo hashtag to document personal stories about the church’s contribution to sexism and violence against women on Twitter.35

Reading Group Guide

Get a FREE ebook by joining our mailing list today! Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

Introduction

In this fascinating look inside white evangelical Christian culture, Linda Kay Klein explores the purity movement that defined her coming of age in the 1990s. Frustrated by her own shame about sex and intimacy, Klein began a twelve-year journey that took her across the country to speak with countless other young women raised in purity culture—women who, like her, were implicitly and explicitly taught that their bodies were dangerous and posed a threat to themselves and others. Pure is the result of her extensive research—part history, part journalism, part memoir—and stands as both a chronicle of pain and a testament to what the human spirit can endure. Through it all, Klein’s faith in God remained steady and led her to seek new churches and communities that might better exemplify her understanding of love, God, and fellowship.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

1. In chapter 1, Linda Kay Klein recalls how, at sixteen, she yearned to prove to herself, her God, and her church that “I was good despite my developing body” (page 39). Why does the separation of the spirit from the body come up again and again in Pure? Does this imposed separation feel particular to the church, or do you think secular culture also promotes a separation between the spirit and the body?

2. Klein was taught to cover herself so as not to threaten the men in the community with sexual temptation. In this regard, she suggests that women are made to bear the burden of responsibility for ensuring sexual propriety. Discuss this phenomenon from your own experience inside and/or outside a church community.

3. On page 14 Klein concludes that “the purity message is not about sex. Rather, it is about us: who we are, who we are expected to be, and who it is said we will become if we fail. . . . This is the language of shame.” Consider how the words (i.e., “pure”) used in purity culture contribute to the sense of shame that Klein and so many others have felt. What word or words stood out to you as you read?

4. Consider the structure of Pure: four sections documenting what purity culture is; challenges faced by girls and women in the church as a result of this culture; challenges girls and women face outside of the church as a result of this culture; and how many individuals and even church communities are finding ways to overcome the damage done by purity culture. Why do you think the author structured the book in this way? If you were to add a fifth section, what would it be, and why?

5. When Chloe confides in Klein that she experimented with oral sex (with girls) as an eight-year-old, she tells Klein she was shamed by her parents, and, at the same time, her parents were shamed by the larger church community. Do you believe that shame can be passed on from one generation to the next? Have you ever seen this happen?

6. “You can’t win” (99), one interviewee laments. Have you ever felt this way when it comes to women and sexuality?

8. Share a time in your life when you questioned an important aspect of your upbringing, whether it was a religious belief or a family tradition or lifestyle.

9. In Muriel’s narrative, she shares that she feels God “in her greatest moments of suffering” (page 148), though the experience is different than she had been taught it would be when she was young. Why do you think Muriel feels this way? What experiences have you had as an adult that looked or felt different than you had thought they would feel when you were young?

10. On pages 178–79, Klein presents the idea of “the gap.” How did Klein overcome the gap in her own life? Could the image of the gap serve as a metaphor for the entire book?

11. Discuss the irony in the conclusion Eli draws about the evangelical community: that the “ideology is more important . . . than people” (page 201). In your experience, do churches and/or other institutionalized cultural communities sometimes sacrifice people for ideology (or the individual for “the greater good”)? If this is the case, can such institutions really be considered communities? Why or why not?

12. In your experience, have you found, like the interviewee Jo, that “women are taught their bodies are evil; men are taught their minds are” (page 235)? If so, why do you think it is that church and society place so much more attention on women’s bodies than on men’s, and on men’s minds than on women’s?

13. Although Pure is a critique of the evangelical purity movement, the author highlights other, positive aspects of the evangelical subculture. On page 276, for example, she describes the “warm, playful teasing” that is typical in the evangelical community. Do you read Pure as a criticism of evangelical Christian culture, or as something else?

14. Discuss the ending of the book. Did it surprise you to learn that Klein’s faith is still strong, if different than before? How did she manage to take ownership of her faith, from your point of view? Have you ever had a similar experience, either of taking ownership of your faith or of something else that you first learned about from others?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. Linda Kay Klein invites us into her personal life—even her bedroom—and in Pure, readers come to form an intimate relationship with the author. Spend more time with Klein’s candor and honesty. With your book club, watch Klein’s TEDx Talk (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bB99HIBT9b4). Afterward, compare how it felt listening to her voice and watching her speak to reading her words on the page.

2. Pure joins the conversation of the #MeToo movement, a conversation that has been long overdue and that is gaining momentum in nearly every industry in the U.S. and abroad. Klein highlights the ways in which evangelical Christianity’s purity movement contributes to larger cultural problems, such as silencing and excusing sexual and gender-based violence. Look into the #MeToo and #ChurchToo hashtags on Twitter with your book club. Review the ways in which the narratives feel similar to or different from the narrative that Klein shares in Pure. Why do you think this movement is happening at this particular cultural moment?

3. Pure offers an ethnographic study of several female experiences in the purity movement. Ethnography, or the “study and systematic recording of human cultures” (Merriam-Webster), can be a fun and hands-on way to conduct research about a subculture. Consider all the subcultures you are a part of, whether they are religious groups, community organizations, or enthusiast groups, and conduct your own informal research into one subculture. Talk to friends and family, take pictures, and offer your own creative reflection on what makes the subculture unique. Share with your book club the results of your efforts. You might be surprised to learn something new about your book club members and perhaps even yourself.

A Conversation with Linda Kay Klein

Pure refers to an extraordinary number of books on shame, religion, and sexuality. If you were to offer one book club suggestion for further reading, which book would it be and why?

Pure is about the ways the purity movement shames white evangelical girls, but we are by no means the only ones suffering because of it. Recently I’ve been learning more about the role that white patriarchal hegemony plays in the purity movement and how this undergirding impacts other communities. Right now I’m reading Sexuality and the Black Church: A Womanist Perspective by the Rev. Dr. Kelly Brown Douglas. I highly recommend it for book clubs interested in broadening their understanding of how these teachings impact various communties, starting with the black church.

What prompted you to begin thinking deeply about the evangelical subculture? Can you pinpoint a specific moment when you felt called to reconsider your relationship to the evangelical church?

If I had to choose just one moment, it would be the moment I write about in the book, when I was sitting on the rocky beach on the edge of the Indian Ocean in Australia and reading those newspaper articles about my youth pastor having attempted to sexually entice a twelve-year-old child under his professional care.

But there’s more to that story than I share in the book. The part about my having been in Australia—an ocean away from my religious community—is important. I was too far away to be told how I was “supposed” to feel about what my youth pastor had done when I learned about it; too far away to listen to the sermon I learned about later in which my congregation was instructed never to talk about what happened because that would be gossip, and gossip was a sin; too far away to be pulled aside and informed I shouldn’t be angry, but should forgive my youth pastor, and learn to let go of the whole horrible situation.

And so, I did talk about what happened.

And I was angry.

And I didn’t let go.

Instead, I wrestled with what happened and how the evangelical church had handled it. And in the midst of that wrestling, I first felt called to reconsider my relationship to the church.

Do you agree with the interviewee Piper that a real danger of the purity movement is the “hatred of self that comes from that lack of place in the community” (page 66)? How have you dealt with your own “lack of place” after leaving the evangelical community in which you were raised?

To be honest, I experienced a lack of place inside the evangelical community more than I ever experienced one outside of it. I first began to feel I didn’t belong in the church when I was in my mid-teens. After all, it’s hard to feel like you belong when you are constantly being pulled aside and told about all of the ways in which you don’t.

After I left, I leaned into a community of creatives. I found my place as a creator—a music-maker, a puppeteer, a performance artist, a visual artist, a writer. I processed the loss of place I had felt in my religious community by writing music, plays, performance pieces, and so on in a creative community.

Who is your target audience for Pure? What message do you hope this audience will receive after reading your book?

This book is written for everyone who has experienced sexual shame.

I hope readers will have new questions to ask themselves, and new conversations that they want to have with others. I hope they will feel less alone. I hope they will feel less hopeless, and just a little more ready to break free.

Describe the research that went into writing this book. What was the process like? Did you uncover any facts that were particularly surprising?

I’ve spent the past twelve years reading, writing, interviewing, investigating, going to courthouses and public libraries across the country, whatever it took to get to the next answer, which inevitably led me to the next question.

During some of this time, I earned an interdisciplinary master’s degree from NYU for which I wrote a thesis focused on white American evangelicalism’s gender and sexuality messaging for girls. I also had the privilege of working alongside gender justice activists to create change within the world’s major religions, from whom I learned a tremendous amount.

What surprised me most were the egregious forms of sexism and abuse I found among some evangelical leaders and institutions in the process. This book is about how everyday purity culture impacts people, not about extremes, so I chose not to refer to these more heinous ideas and actions, but they still haunt me.