Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

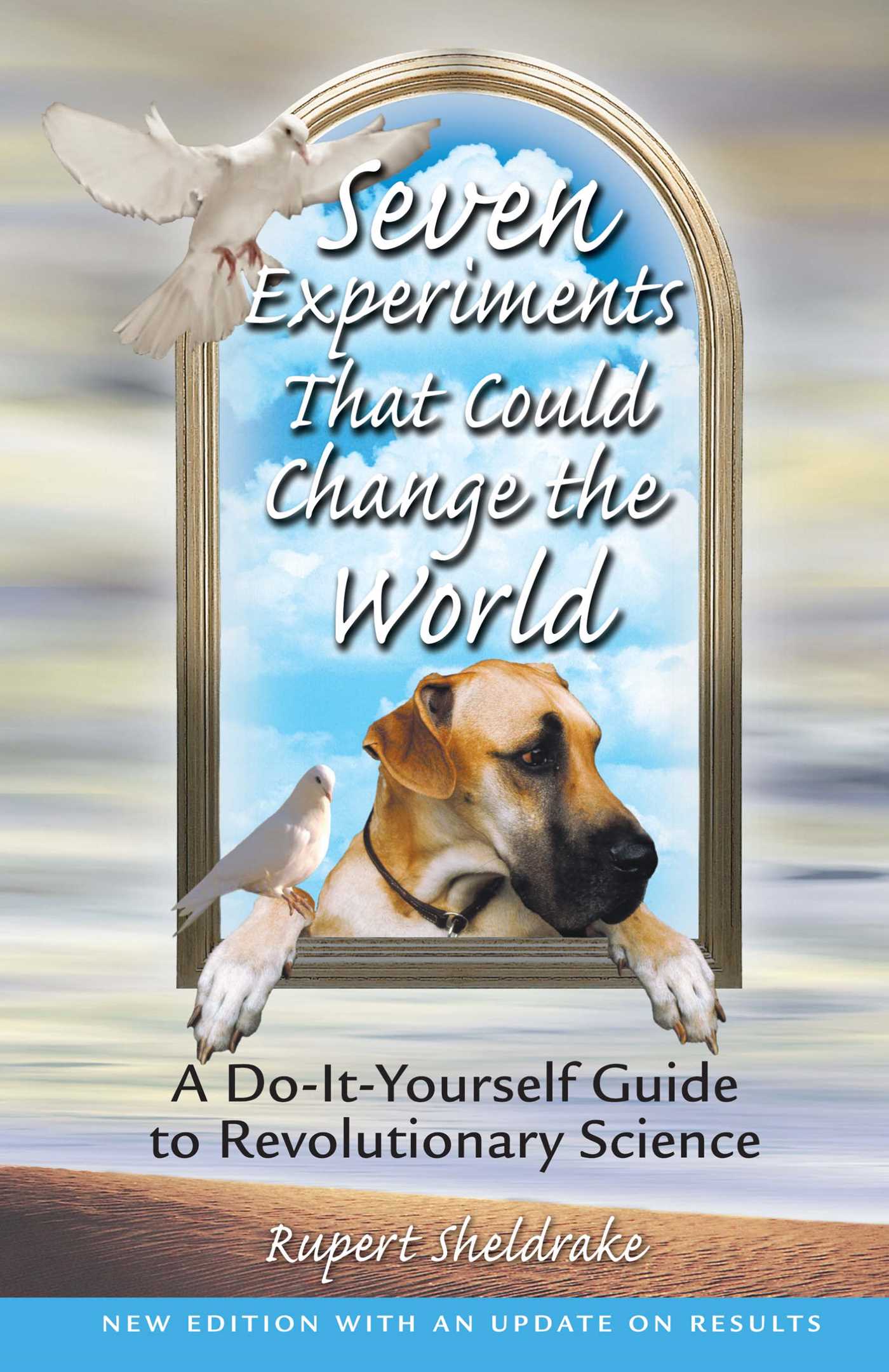

Seven Experiments That Could Change the World

A Do-It-Yourself Guide to Revolutionary Science

Published by Park Street Press

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

Table of Contents

About The Book

Examines the realities of unexplained natural phenomenon and provides explanations that push the boundaries of science.

• Looks at animal telepathy and the ability of pigeons to home.

• Proves the point that "big questions don't need big science".

• Noted scientist Rupert Sheldrake is a former research fellow of the Royal Society.

• New Edition with an Update on Results.

How does your pet "know" when you are coming home? How do pigeons "home"? Can people really feel a "phantom" amputated arm? These questions and more form the basis of Sheldrake's look at the world of contemporary science as he puts some of the most cherished assumptions of established science to the test. What Sheldrake discovers is that certain scientific beliefs are so widely taken for granted that they are no longer regarded as theories but are seen as scientific common sense. In the true spirit of science, Sheldrake examines seven of these beliefs. Refusing to let intellectual dogmatism influence his search for the truth, Sheldrake presents simple experiments that allow the curious and the skeptical to join in his journey of discovery. His experiments look at how scientific research is often biased against unexpected patterns that emerge and how a researcher's expectations can influence the results. He also examines the taboo of taking pets seriously and explores the question of human extrasensory perception. Perhaps most important, he questions the notion that science must be expensive in order to achieve important results, showing that inexpensive methods can indeed shake the very foundations of science as we know it.

In this compelling and intelligent book, Sheldrake offers no preconceived wisdom or easy answers--just an open invitation to explore the unknown, create new science, and perhaps, even change the world.

• Looks at animal telepathy and the ability of pigeons to home.

• Proves the point that "big questions don't need big science".

• Noted scientist Rupert Sheldrake is a former research fellow of the Royal Society.

• New Edition with an Update on Results.

How does your pet "know" when you are coming home? How do pigeons "home"? Can people really feel a "phantom" amputated arm? These questions and more form the basis of Sheldrake's look at the world of contemporary science as he puts some of the most cherished assumptions of established science to the test. What Sheldrake discovers is that certain scientific beliefs are so widely taken for granted that they are no longer regarded as theories but are seen as scientific common sense. In the true spirit of science, Sheldrake examines seven of these beliefs. Refusing to let intellectual dogmatism influence his search for the truth, Sheldrake presents simple experiments that allow the curious and the skeptical to join in his journey of discovery. His experiments look at how scientific research is often biased against unexpected patterns that emerge and how a researcher's expectations can influence the results. He also examines the taboo of taking pets seriously and explores the question of human extrasensory perception. Perhaps most important, he questions the notion that science must be expensive in order to achieve important results, showing that inexpensive methods can indeed shake the very foundations of science as we know it.

In this compelling and intelligent book, Sheldrake offers no preconceived wisdom or easy answers--just an open invitation to explore the unknown, create new science, and perhaps, even change the world.

Excerpt

Page xiii-xv

Because institutional science has become so conservative, so limited by the conventional paradigms, some of the most fundamental problems are either ignored, treated as taboo, or put at the bottom of the scientific agenda. They are anomalies; they don't fit in. For example, the direction-finding abilities of migratory and homing animals, such as monarch butterflies and homing pigeons, are very mysterious. They have not yet been explained in terms of orthodox science, and perhaps they cannot be. But direction-finding by animals is a low-status field of research, compared with, say, molecular biology, and very few scientists work on it. Nevertheless, relatively simple investigations of homing behaviour could transform our under understanding of animal nature, and at the same time lead to the discovery of forces, fields, or influences at preset unknown to physics. And such experiments need cost very little, as I show in this book. They are well within the capacity of many people who are not professional scientists. Indeed those best qualities to do this research would be pigeon fanciers, of whom there are more than five million worldwide.

In the past, most scientific research was carried out by amateurs; and amateurs, by definition, are people who do something because they love it. Charles Darwin, for example, never held any institutional post; he worked independently at his home in Kent, studying barnacles, writing, keeping pigeons, and doing experiments in the garden with his son Francis. Nut from the latter part of the nineteenth century onwards, science has been increasingly professionalized. And since the 1950s, there has been a vast expansion of institutional research. There are now only a handful of independent scientists, the best known being James Lovelock, the leading proponent of the Gaia hypothesis, which is based on the idea that the Earth is a living organism. And although amateur naturalists and freelance inventors still exist, they have been marginalized. . . I envisage a complementary relationship between non-professional and professional researchers, the former having a greater freedom to pioneer new areas of research, and the latter a more rigorous approach, enabling new discoveries to be confirmed and incorporated into the growing body of science.

Because institutional science has become so conservative, so limited by the conventional paradigms, some of the most fundamental problems are either ignored, treated as taboo, or put at the bottom of the scientific agenda. They are anomalies; they don't fit in. For example, the direction-finding abilities of migratory and homing animals, such as monarch butterflies and homing pigeons, are very mysterious. They have not yet been explained in terms of orthodox science, and perhaps they cannot be. But direction-finding by animals is a low-status field of research, compared with, say, molecular biology, and very few scientists work on it. Nevertheless, relatively simple investigations of homing behaviour could transform our under understanding of animal nature, and at the same time lead to the discovery of forces, fields, or influences at preset unknown to physics. And such experiments need cost very little, as I show in this book. They are well within the capacity of many people who are not professional scientists. Indeed those best qualities to do this research would be pigeon fanciers, of whom there are more than five million worldwide.

In the past, most scientific research was carried out by amateurs; and amateurs, by definition, are people who do something because they love it. Charles Darwin, for example, never held any institutional post; he worked independently at his home in Kent, studying barnacles, writing, keeping pigeons, and doing experiments in the garden with his son Francis. Nut from the latter part of the nineteenth century onwards, science has been increasingly professionalized. And since the 1950s, there has been a vast expansion of institutional research. There are now only a handful of independent scientists, the best known being James Lovelock, the leading proponent of the Gaia hypothesis, which is based on the idea that the Earth is a living organism. And although amateur naturalists and freelance inventors still exist, they have been marginalized. . . I envisage a complementary relationship between non-professional and professional researchers, the former having a greater freedom to pioneer new areas of research, and the latter a more rigorous approach, enabling new discoveries to be confirmed and incorporated into the growing body of science.

Product Details

- Publisher: Park Street Press (July 1, 2002)

- Length: 320 pages

- ISBN13: 9781620550069

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"In any generation, there are only a handful of people whose ideas contain the possibility of significantly altering the course of human history. Dr. Rupert Sheldrake is such a person. His ideas offer a real chance for humanity to regain its spiritual bearings. We have been blessed with a rare genius."

– Larry Dossey, M.D., bestselling author of Healing Words

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Seven Experiments That Could Change the World 2nd Edition, Second Edition with an Update on Results eBook 9781620550069