Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

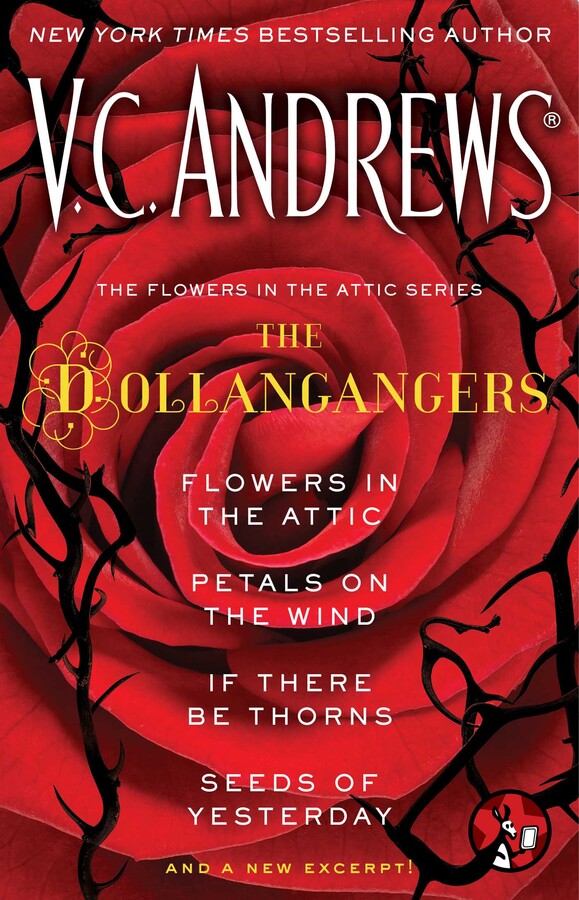

The Flowers in the Attic Series: The Dollangangers

Flowers in the Attic, Petals on the Wind, If There Be Thorns, Seeds of Yesterday, and a New Excerpt!

Part of Dollanganger

By V.C. Andrews

Table of Contents

About The Book

The bestselling Dollanganger series all in one ebook collection!

This ebook boxed set contains the previously published bestselling Dollanganger series by V.C. Andrews, including: Flowers in the Attic, Petals on the Wind, If There Be Thorns, and Seeds of Yesterday.

This ebook boxed set contains the previously published bestselling Dollanganger series by V.C. Andrews, including: Flowers in the Attic, Petals on the Wind, If There Be Thorns, and Seeds of Yesterday.

Excerpt

Good-bye, Daddy

Truly, when I was very young, way back in the Fifties, I believed all of life would be like one long and perfect summer day. After all, it did start out that way. There’s not much I can say about our earliest childhood except that it was very good, and for that, I should be everlastingly grateful. We weren’t rich, we weren’t poor. If we lacked some necessity, I couldn’t name it; if we had luxuries, I couldn’t name those, either, without comparing what we had to what others had, and nobody had more or less in our middleclass neighborhood. In other words, short and simple, we were just ordinary, run-of-the-mill children.

Our daddy was a P.R. man for a large computer manufacturing firm located in Gladstone, Pennsylvania: population, 12,602. He was a huge success, our father, for often his boss dined with us, and bragged about the job Daddy seemed to perform so well. “It’s that all-American, wholesome, devastatingly good-looking face and charming manner that does them in. Great God in heaven, Chris, what sensible person could resist a fella like you?”

Heartily, I agreed with that. Our father was perfect. He stood six feet two, weighed 180 pounds, and his hair was thick and flaxen blond, and waved just enough to be perfect; his eyes were cerulean blue and they sparkled with laughter, with his great zest for living and having fun. His nose was straight and neither too long nor too narrow, nor too thick. He played tennis and golf like a pro and swam so much he kept a suntan all through the year. He was always dashing off on airplanes to California, to Florida, to Arizona, or to Hawaii, or even abroad on business, while we were left at home in the care of our mother.

When he came through the front door late on Friday afternoons—every Friday afternoon (he said he couldn’t bear to be separated from us for longer than five days)—even if it were raining or snowing, the sun shone when he beamed his broad, happy smile on us.

His booming greeting rang out as soon as he put down his suitcase and briefcase: “Come greet me with kisses if you love me!”

Somewhere near the front door, my brother and I would be hiding, and after he’d called out his greeting, we’d dash out from behind a chair or the sofa to crash into his wide open arms, which seized us up at once and held us close, and he warmed our lips with his kisses. Fridays—they were the best days of all, for they brought Daddy home to us again. In his suit pockets he carried small gifts for us; in his suitcases he stored the larger ones to dole out after he greeted our mother, who would hang back and wait patiently until he had done with us.

And after we had our little gifts from his pockets, Christopher and I would back off to watch Momma drift slowly forward, her lips curved in a welcoming smile that lit up our father’s eyes, and he’d take her in his arms, and stare down into her face as if he hadn’t seen her for at least a year.

On Fridays, Momma spent half the day in the beauty parlor having her hair shampooed and set and her fingernails polished, and then she’d come home to take a long bath in perfumed-oiled water. I’d perch in her dressing room, and wait to watch her emerge in a filmy negligee. She’d sit at her dressing table to meticulously apply makeup. And I, so eager to learn, drank in everything she did to turn herself from just a pretty woman into a creature so ravishingly beautiful she didn’t look real. The most amazing part of this was our father thought she didn’t wear makeup! He believed she was naturally a striking beauty.

Love was a word lavished about in our home. “Do you love me?—For I most certainly love you; did you miss me?—Are you glad I’m home?—Did you think about me when I was gone? Every night? Did you toss and turn and wish I were beside you, holding you close? For if you didn’t, Corrine, I might want to die.”

Momma knew exactly how to answer questions like these—with her eyes, with soft whispers and with kisses.

* * *

One day Christopher and I came speeding home from school with the wintery wind blowing us through the front door. “Take off your boots in the foyer,” Momma called out from the living room, where I could see her sitting before the fireplace knitting a little white sweater fit for a doll to wear. I thought it was a Christmas gift for me, for one of my dolls.

“And kick off your shoes before you come in here,” she added.

We shed our boots and heavy coats and hoods in the foyer, then raced in stockinged feet into the living room, with its plush white carpet. That pastel room, decorated to flatter our mother’s fair beauty, was off limits for us most of the time. This was our company room, our mother’s room, and never could we feel really comfortable on the apricot brocade sofa or the cut-velvet chairs. We preferred Daddy’s room, with its dark paneled walls and tough plaid sofa, where we could wallow and fight and never fear we were damaging anything.

“It’s freezing outside, Momma!” I said breathlessly as I fell at her feet, thrusting my legs toward the fire. “But the ride home on our bikes was just beautiful. All the trees are sparkled with diamond icicles, and crystal prisms on the shrubs. It’s a fairyland out there, Momma. I wouldn’t live down south where it never snows, for anything!”

Christopher did not talk about the weather and its freezing beauty. He was two years and five months my senior and he was far wiser than I; I know that now. He warmed his icy feet as I did, but he stared up at Momma’s face, a worried frown drawing his dark brows together.

I glanced up at her, too, wondering what he saw that made him show such concern. She was knitting at a fast and skilled pace, glancing from time to time at instructions.

“Momma, are you feeling all right?” he asked.

“Yes, of course,” she answered, giving him a soft, sweet smile.

“You look tired to me.”

She laid aside the tiny sweater. “I visited my doctor today,” she said, leaning forward to caress Christopher’s rosy cold cheek.

“Momma!” he cried, taking alarm. “Are you sick?”

She chuckled softly, then ran her long, slim fingers through his tousled blond curls. “Christopher Dollanganger, you know better than that. I’ve seen you looking at me with suspicious thoughts in your head.” She caught his hand, and one of mine, and placed them both on her bulging middle.

“Do you feel anything?” she asked, that secret, pleased look on her face again.

Quickly, Christopher snatched his hand away as his face turned blood-red. But I left my hand where it was, wondering, waiting.

“What do you feel, Cathy?”

Beneath my hand, under her clothes, something weird was going on. Little faint movements quivered her flesh. I lifted my head and stared up in her face, and to this day, I can still recall how lovely she looked, like a Raphael madonna.

“Momma, your lunch is moving around, or else you have gas.” Laughter made her blue eyes sparkle, and she told me to guess again.

Her voice was sweet and concerned as she told us her news. “Darlings, I’m going to have a baby in early May. In fact when I visited my doctor today, he said he heard two heartbeats. So that means I am going to have twins . . . or, God forbid, triplets. Not even your father knows this yet, so don’t tell him until I have a chance.”

Stunned, I threw Christopher a look to see how he was taking this. He seemed bemused, and still embarrassed. I looked again at her lovely firelit face. Then I jumped up, and raced for my room!

I hurled myself face down on my bed, and bawled, really let go! Babies—two or more! I was the baby! I didn’t want any little whining, crying babies coming along to take my place! I sobbed and beat at the pillows, wanting to hurt something, if not someone. Then I sat up and thought about running away.

Someone rapped softly on my closed and locked door. “Cathy,” said my mother, “may I come in and talk this over with you?”

“Go away!” I yelled. “I already hate your babies!”

Yes, I knew what was in store for me, the middle child, the one parents didn’t care about. I’d be forgotten; there’d be no more Friday gifts. Daddy would think only of Momma, of Christopher, and those hateful babies that would displace me.

* * *

My father came to me that evening, soon after he arrived home. I’d unlocked the door, just in case he wanted to see me. I stole a peek to see his face, for I loved him very much. He looked sad, and he carried a large box wrapped in silver foil, topped by a huge bow of pink satin.

“How’s my Cathy been?” he asked softly, as I peeked from beneath my arm. “You didn’t run to greet me when I came home. You haven’t said hello; you haven’t even looked at me. Cathy, it hurts when you don’t run into my arms and give me kisses.”

I didn’t say anything, but rolled over on my back to glare at him fiercely. Didn’t he know I was supposed to be his favorite all his life through? Why did he and Momma have to go and send for more children? Weren’t two enough?

He sighed, then came to sit on the edge of my bed. “You know something? This is the first time in your life you have ever glared at me like that. This is the first Friday you haven’t run to leap up into my arms. You may not believe this, but I don’t really come alive until I come home on weekends.”

Pouting, I refused to be won over. He didn’t need me now. He had his son, and now heaps of wailing babies on the way. I’d be forgotten in the multitude.

“You know something else,” he began, closely watching me, “I used to believe, perhaps foolishly, that if I came home on Fridays, and didn’t bring one single gift for you, or your brother . . . I still believed the two of you would have run for me like crazy, and welcomed me home, anyway. I believed you loved me and not my gifts. I mistakenly believed that I’d been a good father, and somehow I’d managed to win your love, and that you’d know you would always have a big place in my heart, even if your mother and I have a dozen children.” He paused, sighed, and his blue eyes darkened. “I thought my Cathy knew she would still be my very special girl, because she was my first.”

I threw him an angry, hurt look. Then I choked, “But if Momma has another girl, you’ll say the same thing to her!”

“Will I?”

“Yes,” I sobbed, aching so badly I could scream from jealousy already. “You might even love her more than you do me, ’cause she’ll be little and cuter.”

“I may love her as much, but I won’t love her more.” He held out his arms and I could resist no longer. I flung myself into his arms, and clung to him for dear life. “Ssh,” he soothed as I cried. “Don’t cry, don’t feel jealous. You won’t be loved any the less. And Cathy, real babies are much more fun than dolls. Your mother will have more than she can handle, so she’s going to depend on you to help her. When I’m away from home, I’ll feel better knowing your mother has a loving daughter who will do what she can to make life easier and better for all of us.” His warm lips pressed against my teary cheek. “Come now, open your box, and tell me what you think of what’s inside.”

First I had to smother his face with a dozen kisses and give him bear hugs to make up for the anxiety I’d put in his eyes. In the beautiful box was a silver music box made in England. The music played and a ballerina dressed in pink turned slowly around and around before a mirror. “It’s a jewel box, as well,” explained Daddy, slipping on my finger a tiny gold ring with a red stone he called a garnet. “The moment I saw that box, I knew you had to have it. And with this ring, I do vow to forever love my Cathy just a little bit more than any other daughter—as long as she never says that to anyone but herself.”

* * *

There came a sunny Tuesday in May, when Daddy was home. For two weeks Daddy had been hanging around home, waiting for those babies to show up. Momma seemed irritable, uncomfortable, and Mrs. Bertha Simpson was in our kitchen, preparing our meals, and looking at Christopher and me with a smirky face. She was our most dependable baby-sitter. She lived next door, and was always saying Momma and Daddy looked more like brother and sister than husband and wife. She was a grim, grouchy sort of person who seldom had anything nice to say about anybody. And she was cooking cabbage. I hated cabbage.

Around dinnertime, Daddy came rushing into the dining room to tell my brother and me that he was driving Momma to the hospital. “Now don’t be worried. Everything will work out fine. Mind Mrs. Simpson, and do your homework, and maybe in a few hours you’ll know if you have brothers or sisters . . . or one of each.”

He didn’t return until the next morning. He was unshaven, tired looking, his suit rumpled, but he grinned at us happily. “Take a guess! Boys or girls?”

“Boys!” chimed up Christopher, who wanted two brothers he could teach to play ball. I wanted boys, too . . . no little girl to steal Daddy’s affection from his first daughter.

“A boy and a girl,” Daddy said proudly. “The prettiest little things you ever saw. Come, put your clothes on, and I’ll drive you to see them yourselves.”

Sulkily, I went, still reluctant to look even when Daddy picked me up and held me high so I could peer through the nursery room glass at two little babies a nurse held in her arms. They were so tiny! Their heads were no bigger than small apples, and small red fists waved in the air. One was screaming like pins were sticking it.

“Ah,” sighed Daddy, kissing my cheek and hugging me close, “God has been good to me, sending me another son and daughter as perfect as my first pair.”

I thought I would hate them both, especially the loudmouthed one named Carrie, who wailed and bellowed ten times louder than the quiet one named Cory. It was nearly impossible to get a full night’s rest with the two of them across the hall from my room. And yet, as they began to grow and smile, and their eyes lit up when I came in and lifted them, something warm and motherly replaced the green in my eyes. The first thing you knew, I was racing home to see them; to play with them; to change diapers and hold nursing bottles, and burp them on my shoulder. They were more fun than dolls.

I soon learned that parents have room in their hearts for more than two children, and I had room in my heart to love them, too—even Carrie, who was just as pretty as me, and maybe more so. They grew so quickly, like weeds, said Daddy, though Momma would often look at them with anxiety, for she said they were not growing as rapidly as Christopher and I had grown. This was laid before her doctor, who quickly assured her that often twins were smaller than single births.

“See,” said Christopher, “doctors do know everything.”

Daddy looked up from the newspaper he was reading and smiled. “That’s my son the doctor talking—but nobody knows everything, Chris.”

Daddy was the only one who called my older brother Chris.

We had a funny surname, the very devil to learn to spell. Dollanganger. Just because we were all blond, flaxon haired, with fair complexions (except Daddy, with his perpetual tan), Jim Johnston, Daddy’s best friend, pinned on us a nickname, “The Dresden dolls.” He said we looked like those fancy porcelain people who grace whatnot shelves and fireplace mantels. Soon everyone in our neighborhood was calling us the Dresden dolls; certainly it was easier to say than Dollanganger.

When the twins were four, and Christopher was fourteen, and I had just turned twelve, there came a very special Friday. It was Daddy’s thirty-sixth birthday and we were having a surprise party for him. Momma looked like a fairy-tale princess with her freshly washed and set hair. Her nails gleamed with pearly polish, her long formal gown was of softest aqua color, and her knotted string of pearls swayed as she glided from here to there, setting the table in the dining room so it would look perfect for Daddy’s birthday party. His many gifts were piled high on the buffet. It was going to be a small, intimate party, just for our family and our closest friends.

“Cathy,” said Momma, throwing me a quick look, “would you mind bathing the twins again for me? I gave them both baths before their naps, but as soon as they were up, they took off for the sandbox, and now they need another bath.”

I didn’t mind. She looked far too fancy to give two dirty four-year-olds splashy baths that would ruin her hair, her nails, and her lovely dress.

“And when you finish with them, both you and Christopher jump in the tub and bathe, too, and put on that pretty new pink dress, Cathy, and curl your hair. And, Christopher, no blue jeans, please. I want you to put on a dress shirt and a tie, and wear that light blue sports jacket with your cream-colored trousers.”

“Aw, heck, Momma, I hate dressing up,” he complained, scuffing his sneakers and scowling.

“Do as I say, Christopher, for your father. You know he does a lot for you; the least you can do is make him proud of his family.”

He grouched off, leaving me to run out to the back garden and fetch the twins, who immediately began to wail. “One bath a day is enough!” screamed Carrie. “We’re already clean! Stop! We don’t like soap! We don’t like hair washings! Don’t you do that to us again, Cathy, or we’ll tell Momma!”

“Hah!” I said. “Who do you think sent me out here to clean up two filthy little monsters? Good golly, how can the two of you get so dirty so quickly?”

As soon as their naked skins hit the warm water, and the little yellow rubber ducks and rubber boats began to float, and they could splash all over me, they were content enough to be bathed, shampooed, and dressed in their very best clothes. For, after all, they were going to a party—and, after all, this was Friday, and Daddy was coming home.

First I dressed Cory in a pretty little white suit with short pants. Strangely enough, he was more apt to keep himself clean than his twin. Try as I would, I couldn’t tame down that stubborn cowlick of his. It curled over to the right, like a cute pig’s tail, and—would you believe it?—Carrie wanted her hair to do the same thing!

When I had them both dressed, and looking like dolls come alive, I turned the twins over to Christopher with stern warnings to keep an ever observant eye on them. Now it was my turn to dress up.

The twins wailed and complained while I hurriedly took a bath, washed my hair, and rolled it up on fat curlers. I peeked around the bathroom door to see Christopher trying his best to entertain them by reading to them from Mother Goose.

“Hey,” said Christopher when I came out wearing my pink dress with the fluted ruffles, “you don’t look half-bad.”

“Half-bad? Is that the best you can manage?”

“Best I can for a sister.” He glanced at his watch, slammed the picture book closed, seized the twins by their dimpled hands and cried out, “Daddy will be here any minute—hurry, Cathy!”

* * *

Five o’clock came and went, and though we waited and waited, we didn’t see our father’s green Cadillac turn into our curving drive. The invited guests sat around and tried to keep up a cheerful conversation, as Momma got up and began to pace around nervously. Usually Daddy flung open the door at four, and sometimes even sooner.

Seven o’clock, and still we were waiting.

The wonderful meal Momma had spent so much time preparing was drying out from being too long in the warming oven. Seven was the time we usually put the twins to bed, and they were growing hungry, sleepy and cross, demanding every second, “When is Daddy coming?”

Their white clothes didn’t look so virgin now. Carrie’s smoothly waved hair began to curl up and look windblown. Cory’s nose began to run, and repeatedly he wiped it on the back of his hand until I hurried over with a Kleenex to clean off his upper lip.

“Well, Corinne,” joked Jim Johnston, “I guess Chris has found himself another super-broad.”

His wife threw him an angry look for saying something so tasteless.

My stomach was growling, and I was beginning to feel as worried as Momma looked. She kept pacing back and forth, going to the wide picture window and staring out.

“Oh!” I cried, having caught sight of a car turning into our tree lined driveway, “maybe that’s Daddy coming now!”

But the car that drew to a stop before our front door was white, not green. And on the top was one of those spinning red lights. An emblem on the side of that white car read STATE POLICE.

Momma smothered a cry when two policemen dressed in blue uniforms approached our front door and rang our doorbell.

Momma seemed frozen. Her hand hovered near her throat; her heart came up and darkened her eyes. Something wild and frightening burgeoned in my heart just from watching her reactions.

It was Jim Johnston who answered the door, and allowed the two state troopers to enter, glancing about uneasily, seeing, I’m sure, that this was an assembly gathered together for a birthday party. All they had to do was glance into the dining room and see the festive table, the balloons suspended from the chandelier, and the gifts on the buffet.

“Mrs. Christopher Garland Dollanganger?” inquired the older of the two officers as he looked from woman to woman.

Our mother nodded slightly, stiffly. I drew nearer, as did Christopher. The twins were on the floor, playing with tiny cars, and they showed little interest in the unexpected arrival of police officers.

The kindly looking uniformed man with the deep red face stepped closer to Momma. “Mrs. Dollanganger,” he began in a flat voice that sent immediate panic into my heart, “we’re terribly sorry, but there’s been an accident on Greenfield Highway.”

“Oh . . .” breathed Momma, reaching to draw both Christopher and me against her sides. I could feel her quivering all over, just as I was. My eyes were magnetized by those brass buttons; I couldn’t see anything else.

“Your husband was involved, Mrs. Dollanganger.”

A long sigh escaped from Momma’s choked throat. She swayed and would have fallen if Chris and I hadn’t been there to support her.

“We’ve already questioned motorists who witnessed the accident, and it wasn’t your husband’s fault, Mrs. Dollanganger,” that voice continued on, without emotion. “According to the accounts, which we’ve recorded, there was a motorist driving a blue Ford weaving in and out of the lefthand lane, apparently drunk, and he crashed head-on into your husband’s car. But it seems your husband must have seen the accident coming, for he swerved to avoid a head-on collision, but a piece of machinery had fallen from another car, or truck, and this kept him from completing his correct defensive driving maneuver, which would have saved his life. But as it was, your husband’s much heavier car turned over several times, and still he might have survived, but an oncoming truck, unable to stop, crashed into his car, and again the Cadillac spun over . . . and then . . . it caught on fire.”

Never had a room full of people stilled so quickly. Even the young twins looked up from their innocent play, and stared at the two troopers.

“My husband?” whispered Momma, her voice so weak it was hardly audible. “He isn’t . . . he isn’t . . . dead . . . ?”

“Ma’am,” said the red-faced officer very solemnly, “it pains me dreadfully to bring you bad news on what seems a special occasion.” He faltered and glanced around with embarrassment. “I’m terribly sorry, ma’am—everybody did what they could to get him out . . . but, well ma’am . . . he was, well, killed instantly, from what the doc says.”

Someone sitting on the sofa screamed.

Momma didn’t scream. Her eyes went bleak, dark, haunted. Despair washed the radiant color from her beautiful face; it resembled a death mask. I stared up at her, trying to tell her with my eyes that none of this could be true. Not Daddy! Not my daddy! He couldn’t be dead . . . he couldn’t be! Death was for old people, sick people . . . not for somebody as loved and needed, and young.

Yet there was my mother with her gray face, her stark eyes, her hands wringing out the invisible wet cloths, and each second I watched, her eyes sank deeper into her skull.

I began to cry.

“Ma’am, we’ve got a few things of his that were thrown out on the first impact. We saved what we could.”

“Go away!” I screamed at the officer. “Get out of here! It’s not my daddy! I know it’s not! He’s stopped by a store to buy ice cream. He’ll be coming in the door any minute! Get out of here!” I ran forward and beat on the officer’s chest. He tried to hold me off, and Christopher came up and pulled me away.

“Please,” said the trooper, “won’t someone please help this child?”

My mother’s arms encircled my shoulders and drew me close to her side. People were murmuring in shocked voices, and whispering, and the food in the warming oven was beginning to smell burned.

I waited for someone to come up and take my hand and say that God didn’t ever take the life of a man like my father, yet no one came near me. Only Christopher came to put his arm about my waist, so we three were in a huddle,—Momma, Christopher, and me.

It was Christopher who finally found a voice to speak and such a strange, husky voice: “Are you positive it was our father? If the green Cadillac caught on fire, then the man inside must have been badly burned, so it could have been someone else, not Daddy.”

Deep, rasping sobs tore from Momma’s throat, though not a tear fell from her eyes. She believed! She believed those two men were speaking the truth!

The guests who had come so prettily dressed to attend a birthday party swarmed about us now and said those consoling things people say when there just aren’t any right words.

“We’re so sorry, Corinne, really shocked . . . it’s terrible . . . .”

“What an awful thing to happen to Chris.”

“Our days are numbered . . . that’s the way it is, from the day we’re born, our days are numbered.”

It went on and on, and slowly, like water into concrete, it sank in. Daddy was really dead. We were never going to see him alive again. We’d only see him in a coffin, laid out in a box that would end up in the ground, with a marble headstone that bore his name and his day of birth and his day of death. Numbered the same, but for the year.

I looked around, to see what was happening to the twins, who shouldn’t have been feeling what I was. Someone kind had taken them into the kitchen and was preparing them a light meal before they were tucked into bed. My eyes met Christopher’s. He seemed as caught in this nightmare as I was, his young face pale and shocked; a hollow look of grief shadowed his eyes and made them dark.

One of the state troopers had gone out to his car, and now he came back with a bundle of things which he carefully spread out on the coffee table. I stood frozen, watching the display of all the things Daddy kept in his pockets: a lizard-skinned wallet Momma had given him as a Christmas gift; his leather notepad and date book; his wristwatch; his wedding band. Everything was blackened and charred by smoke and fire.

Last came the soft pastel animals meant for Cory and Carrie, all found, so the red-faced trooper said, scattered on the highway. A plushy blue elephant with pink velvet ears, and a purple pony with a red saddle and golden reins—oh, that just had to be for Carrie. Then the saddest articles of all—Daddy’s clothes, which had burst the confines of his suitcases when the trunk lock sprang.

I knew those suits, those shirts, ties, socks. There was the same tie I had given him on his last birthday.

“Someone will have to identify the body,” said the trooper.

Now I knew positively. It was real, our father would never come home without presents for all of us—even on his own birthday.

I ran from that room! Ran from all the things spread out that tore my heart and made me ache worse than any pain I had yet experienced. I ran out of the house and into the back garden, and there I beat my fists upon an old maple tree. I beat my fists until they ached and blood began to come from the many small cuts; then I flung myself down on the grass and cried—cried ten oceans of tears, for Daddy who should be alive. I cried for us, who would have to go on living without him. And the twins, they hadn’t even had the chance to know how wonderful he was—or had been. And when my tears were over, and my eyes swollen and red, and hurt from the rubbing, I heard soft footsteps coming to me—my mother.

She sat down on the grass beside me and took my hand in hers. A quarter-horned moon was out, and millions of stars, and the breezes were sweet with the newborn fragrances of spring. “Cathy,” she said eventually when the silence between us stretched so long it might never come to an end, “your father is up in heaven looking down on you, and you know he would want you to be brave.”

“He’s not dead, Momma!” I denied vehemently.

“You’ve been out in this yard a long time; perhaps you don’t realize it’s ten o’clock. Someone had to identify your father’s body, and though Jim Johnston offered to do this, and spare me the pain, I had to see for myself. For, you see, I found it hard to believe too. Your father is dead, Cathy. Christopher is on his bed crying, and the twins are asleep; they don’t fully realize what ‘dead’ means.”

She put her arms around me, and cradled my head down on her shoulder.

“Come,” she said, standing and pulling me up with her, keeping her arm about my waist, “You’ve been out here much too long. I thought you were in the house with the others, and the others thought you were in your room, or with me. It’s not good to be alone when you feel bereft. It’s better to be with people and share your grief, and not keep it locked up inside.”

She said this dry-eyed, with not a tear, but somewhere deep inside her she was crying, screaming. I could tell by her tone, by the very bleakness that had sunk deeper into her eyes.

* * *

With our father’s death, a nightmare began to shadow our days. I gazed reproachfully at Momma and thought she should have prepared us in advance for something like this, for we’d never been allowed to own pets that suddenly pass away and teach us a little about losing through death. Someone, some adult, should have warned us that the young, the handsome, and the needed can die, too.

How do you say things like this to a mother who looked like fate was pulling her through a knothole and stretching her out thin and flat? Could you speak honestly to someone who didn’t want to talk, or eat, or brush her hair, or put on the pretty clothes that filled her closet? Nor did she want to attend to our needs. It was a good thing the kindly neighborhood women came in and took us over, bringing with them food prepared in their own kitchens. Our house filled to overflowing with flowers, with homemade casseroles, hams, hot rolls, cakes, and pies.

They came in droves, all the people who loved, admired, and respected our father, and I was surprised he was so well known. Yet I hated it every time someone asked how he died, and what a pity someone so young should die, when so many who were useless and unfit, lived on and on, and were a burden to society.

From all that I heard, and overheard, fate was a grim reaper, never kind, with little respect for who was loved and needed.

Spring days passed on toward summer. And grief, no matter how you try to cater to its wail, has a way of fading away, and the person so real, so beloved, becomes a dim, slightly out-of-focus shadow.

One day Momma sat so sad-faced that she seemed to have forgotten how to smile. “Momma,” I said brightly, in an effort to cheer her, “I’m going to pretend Daddy is still alive, and away on another of his business trips, and soon he’ll come, and stride in the door, and he’ll call out, just as he used to, ‘Come and greet me with kisses if you love me.’ And—don’t you see?—we’ll feel better, all of us, like he is alive somewhere, living where we can’t see him, but where we can expect him at any moment.”

“No, Cathy,” Momma flared, “you must accept the truth. You are not to find solace in pretending. Do you hear that! Your father is dead, and his soul has gone on to heaven, and you should understand at your age that no one ever has come back from heaven. As for us, we’ll make do the best we can without him—and that doesn’t mean escaping reality by not facing up to it.”

I watched her rise from her chair and begin to take things from the refrigerator to start breakfast.

“Momma . . .” I began again, feeling my way along cautiously lest she turn hard and angry again. “Will we be able to go on, without him?”

“I will do the best I can to see that we survive,” she said dully, flatly.

“Will you have to go to work now, like Mrs. Johnston?”

“Maybe, maybe not. Life holds all sorts of surprises, Cathy, and some of them are unpleasant, as you are finding out. But remember always you were blessed to have for almost twelve years a father who thought you were something very special.”

“Because I look like you,” I said, still feeling some of that envy I always had, because I came in second after her.

She threw me a glance as she rambled through the contents of the jam-packed fridge. “I’m going to tell you something now, Cathy, that I’ve never told you before. You look very much as I did at your age, but you are not like me in your personality. You are much more aggressive, and much more determined. Your father used to say that you were like his mother, and he loved his mother.”

“Doesn’t everybody love their mother?”

“No,” she said with a queer expression, “there are some mothers you just can’t love, for they don’t want you to love them.”

She took bacon and eggs from the refrigerator, then turned to take me in her arms. “Dear Cathy, you and your father had a very special close relationship, and I guess you must miss him more because of that, more than Christopher does, or the twins.”

I sobbed against her shoulder. “I hate God for taking him! He should have lived to be an old man! He won’t be there when I dance and when Christopher is a doctor. Nothing seems to matter now that he’s gone.”

“Sometimes,” she began in a tight voice, “death is not as terrible as you think. Your father will never grow old, or infirm. He’ll always stay young; you’ll remember him that way—young, handsome, strong. Don’t cry anymore, Cathy, for as your father used to say, there is a reason for everything and a solution for every problem, and I’m trying, trying hard to do what I think best.”

We were four children stumbling around in the broken pieces of our grief and loss. We would play in the back garden, trying to find solace in the sunshine, quite unaware that our lives were soon to change so drastically, so dramatically, that the words “backyard” and “garden” were to become for us synonyms for heaven—and just as remote.

It was an afternoon shortly after Daddy’s funeral, and Christopher and I were with the twins in the backyard. They sat in the sandbox with small shovels and sand pails. Over and over again they transferred sand from one pail to another, gibbering back and forth in the strange language only they could understand. Cory and Carrie were fraternal rather than identical twins, yet they were like one unit, very much satisfied with each other. They built a wall about themselves so they were the castle-keeps, and full guardians of their larder of secrets. They had each other and that was enough.

The time for dinner came and went. We were afraid that now even meals might be cancelled, so even without our mother’s voice to call us in, we caught hold of the dimpled, fat hands of the twins and dragged them along toward the house. We found our mother seated behind Daddy’s big desk; she was writing what appeared to be a very difficult letter, if the evidence of many discarded beginnings meant anything. She frowned as she wrote in longhand, pausing every so often to lift her head and stare off into space.

“Momma,” I said, “it’s almost six o’clock. The twins are growing hungry.”

“In a minute, in a minute,” she said in an off-hand way. “I’m writing to your grandparents who live in Virginia. The neighbors have brought us food enough for a week—you could put one of the casseroles in the oven, Cathy.”

It was the first meal I almost prepared myself. I had the table set, and the casserole heating, and the milk poured, when Momma came in to help.

It seemed to me that every day after our father had gone, our mother had letters to write, and places to go, leaving us in the care of the neighbor next door. At night Momma would sit at Daddy’s desk, a green ledger book opened in front of her, checking over stacks of bills. Nothing felt good anymore, nothing. Often now my brother and I bathed the twins, put on their pajamas, and tucked them into bed. Then Christopher would hurry off to his room to study, while I would hurry back to my mother to seek a way to bring happiness to her eyes again.

A few weeks later a letter came in response to the many our mother had written home to her parents. Immediately Momma began to cry—even before she had opened the thick, creamy envelope, she cried. Clumsily, she used a letter opener, and with trembling hands she held three sheets, reading over the letter three times. All the while she read, tears trickled slowly down her cheeks, smearing her makeup with long, pale, shiny streaks.

She had called us in from the backyard as soon as she had collected the mail from the box near the front door, and now we four were seated on the living room sofa. As I watched I saw her soft fair Dresden face turn into something cold, hard, resolute. A cold chill shivered down my spine. Maybe it was because she stared at us for so long—too long. Then she looked down at the sheets held in her trembling hands, then to the windows, as if there she could find some answer to the question of the letter.

Momma was acting so strangely. It made us all uneasy and unusually quiet, for we were already intimidated enough in a fatherless home without a creamy letter of three sheets to glue our mother’s tongue and harden her eyes. Why did she look at us so oddly?

Finally, she cleared her throat and began to speak, but in a cold voice, totally unlike her customary soft, warm cadence. “Your grandmother has at last replied to my letters,” she said in that icy voice. “All those letters I wrote to her . . . well . . . she has agreed. She is willing to let us come and live with her.”

Good news! Just what we had been waiting to hear—and we should have been happy. But Momma fell into that moody silence again, and she just sat there staring at us. What was the matter with her? Didn’t she know we were hers, and not some stranger’s four perched in a row like birds on a clothesline?

“Christopher, Cathy, at fourteen and twelve, you two should be old enough to understand, and old enough to cooperate, and help your mother out of a desperate situation.” She paused, fluttered one hand up to nervously finger the beads at her throat and sighed heavily. She seemed on the verge of tears. And I felt sorry, so sorry for poor Momma, without a husband.

“Momma,” I said, “is everything all right?”

“Of course, darling, of course.” She tried to smile. “Your father, God rest his soul, expected to live to a ripe old age and acquire in the meantime a sizable fortune. He came from people who know how to make money, so I don’t have any doubts he would have done just what he planned, if given the time. But thirty-six is so young to die. People have a way of believing nothing terrible will ever happen to them, only to others. We don’t anticipate accidents, nor do we expect to die young. Why, your father and I thought we would grow old together, and we hoped to see our grandchildren before we both died on the same day. Then neither of us would be left alone to grieve for the one who went first.”

Again she sighed. “I have to confess we lived way beyond our present means, and we charged against the future. We spent money before we had it. Don’t blame him; it was my fault. He knew all about poverty. I knew nothing about it. You know how he used to scold me. Why, when we bought this house, he said we needed only three bedrooms, but I wanted four. Even four didn’t seem enough. Look around, there’s a thirty year mortgage on this house. Nothing here is really ours: not this furniture, not the cars, not the appliances in the kitchen or laundry room—not one single thing is fully paid for.”

Did we look frightened? Scared? She paused as her face flushed deeply red, and her eyes moved around the lovely room that set off her beauty so well. Her delicate brows screwed into an anxious frown. “Though your father would chastise me a little, still he wanted them, too. He indulged me, because he loved me, and I believe I convinced him finally that luxuries were absolute necessities, and he gave in, for we had a way, the two of us, of indulging our desires too much. It was just another of the things we had in common.”

Her expression collapsed into one of forlorn reminiscence before she continued on in her stranger’s voice. “Now all our beautiful things will be taken away. The legal term is repossession. That’s what they do when you don’t have enough money to finish paying for what you’ve bought. Take that sofa, for example. Three years ago it cost eight hundred dollars. And we’ve paid all but one hundred, but still they’re going to take it. We’ll lose all that we’ve paid on everything, and that’s still legal. Not only will we lose this furniture and the house, but also the cars—in fact, everything but our clothes and your toys. They’re going to allow me to keep my wedding band, and I’ve hidden away my engagement diamond—so please don’t mention I ever had an engagement ring to anyone who might come to check.”

Who “they” were, not one of us asked. It didn’t occur to me to ask. Not then. And later it just didn’t seem to matter.

Christopher’s eyes met mine. I floundered in the desire to understand, and struggled not to drown in the understanding. Already I was sinking, drowning in the adult world of death and debts. My brother reached out and took my hand, then squeezed my fingers in a gesture of unusual brotherly reassurance.

Was I a windowpane, so easy to read, that even he, my arch-tormentor, would seek to comfort me? I tried to smile, to prove to him how adult I was, and in this way gloss over that trembling and weak thing I was cringing into because “they” were going to take everything. I didn’t want any other little girl living in my pretty peppermint pink room, sleeping in my bed, playing with the things I cherished—my miniature dolls in their shadowbox frames, and my sterling-silver music box with the pink ballerina—would they take those, too?

Momma watched the exchange between my brother and me very closely. She spoke again with a bit of her former sweet self showing. “Don’t look so heartbroken. It’s not really as bad as I’ve made it seem. You must forgive me if I was thoughtless and forgot how young you still are. I’ve told you the bad news first, and saved the best for the last. Now hold your breath! You are not going to believe what I have to tell you—for my parents are rich! Not middle-class rich, or upper-class rich, but very, very rich! Filthy, unbelievably, sinfully rich! They live in a fine big house in Virginia—such a house as you’ve never seen before. I know, I was born there, and grew up there, and when you see that house, this one will seem like a shack in comparison. And didn’t I say we are going to live with them—my mother, and my father?”

She offered this straw of cheer with a weak and nervously fluttering smile that did not succeed in releasing me from doubts which her demeanor and her information had pitched me into. I didn’t like the way her eyes skipped guiltily away when I tried to catch them. I thought she was hiding something.

But she was my mother.

And Daddy was gone.

I picked up Carrie and sat her on my lap, pressing her small, warm body close against mine. I smoothed back the damp golden curls that fell over her rounded forehead. Her eyelids drooped, and her full rosebud lips pouted. I glanced at Cory, crouching against Christopher. “The twins are tired, Momma. They need their dinner.”

“Time enough for dinner later,” she snapped impatiently. “We have plans to make, and clothes to pack, for tonight we have to catch a train. The twins can eat while we pack. Everything you four wear must be crowded into only two suitcases. I want you to take only your favorite clothes and the small toys you cannot bear to leave. Only one game. I’ll buy you many games after you are there. Cathy, you select what clothes and toys you think the twins like best—but only a few. We can’t take along more than four suitcases, and I need two for my own things.”

Oh, golly-lolly! This was real! We had to leave, abandon everything! I had to crowd everything into two suitcases my brothers and sister would share as well. My Raggedy Ann doll alone would half fill one suitcase! Yet how could I leave her, my most beloved doll, the one Daddy gave me when I was only three? I sobbed.

So, we sat with our shocked faces staring at Momma. We made her terribly uneasy, for she jumped up and began to pace the room.

“As I said before, my parents are extremely wealthy.” She shot Christopher and me an appraising glance, then quickly turned to hide her face.

“Momma,” said Christopher, “is something wrong?”

I marveled that he could ask such a thing, when it was only too obvious, everything was wrong.

She paced, her long shapely legs appearing through the front opening of her filmy black negligee. Even in her grief, wearing black, she was beautiful—shadowed, troubled eyes and all. She was so lovely, and I loved her,—oh, how I loved her then!

How we all loved her then.

Directly in front of the sofa, our mother spun around and the black chiffon of her negligee flared like a dancer’s skirt, revealing her beautiful legs from feet to hips.

“Darlings,” she began, “what could possibly be wrong about living in such a fine home as my parents own? I was born there; I grew up there, except for those years when I was sent away to school. It’s a huge, beautiful house, and they keep adding new rooms to it, though Lord knows they have enough rooms already.”

She smiled, but something about her smile seemed false. “There is, however, one small thing I have to tell you before you meet my father—your grandfather.” Here again she faltered, and again smiled that queer, shadowy smile. “Years ago, when I was eighteen, I did something serious, of which your grandfather disapproved, and my mother wasn’t approving, either, but she wouldn’t leave me anything, anyway, so she doesn’t count. But, because of what I did, my father had me written out of his will, and so now I am disinherited. Your father used to gallantly call this ‘fallen from grace.’ Your father always made the best of everything, and he said it didn’t matter.”

Fallen from grace? Whatever did that mean? I couldn’t imagine my mother doing anything so bad that her own father would turn against her and take away what she should have.

“Yes, Momma, I know exactly what you mean,” Christopher piped up. “You did something of which your father disapproved, and so, even though you were included in his will, he had his lawyer write you out instead of thinking twice, and now you won’t inherit any of his worldly goods when he passes on to the great beyond.” He grinned, pleased with himself for knowing more than me. He always had the answers to everything. He had his nose in a book whenever he was in the house. Outside, under the sky, he was just as wild, just as mean as any other kid on the block. But indoors, away from the television, my older brother was a bookworm!

Naturally, he was right.

“Yes, Christopher. None of your grandfather’s wealth will come to me when he dies, or through me, to you. That’s why I had to keep writing so many letters home when my mother didn’t respond.” Again she smiled, this time with bitter irony. “But, since I am the sole heir left, I am hopeful of winning back his approval. You see, once I had two older brothers, but both have died in accidents, and now I am the only one left to inherit.” Her restless pacing stopped. Her hand rose to cover her mouth; she shook her head, then said in a new parrot-like voice, “I guess I’d better tell you something else. Your real surname is not Dollanganger; it is Foxworth. And Foxworth is a very important name in Virginia.”

“Momma!” I exclaimed in shock. “Is it legal to change your name, and put that fake name on our birth certificates?”

Her voice became impatient. “For heaven’s sake, Cathy, names can be changed legally. And the name Dollanganger does belong to us, more or less. Your father borrowed that name from way back in his ancestry. He thought it an amusing name, a joke, and it served its purpose well enough.”

“What purpose?” I asked. “Why would Daddy legally change his name from something like Foxworth, so easy to spell, to something long and difficult like Dollanganger?”

“Cathy, I’m tired,” said Momma, falling into the nearest chair. “There’s so much for me to do, so many legal details. Soon enough you’ll know everything; I’ll explain. I swear to be totally honest; but please, now, let me catch my breath.”

Oh, what a day this was. First we hear the mysterious “they” were coming to take away all our things, even our house. And then we learn even our own last name wasn’t really ours.

The twins, curled up on our laps, were already half-asleep, and they were too young to understand, anyway. Even I, now twelve years old, and almost a woman, could not comprehend why Momma didn’t really look happy to be going home again to parents she hadn’t seen in fifteen years. Secret grandparents we’d thought were dead until after our father’s funeral. Only this day had we heard of two uncles who’d died in accidents. It dawned on me strongly then, that our parents had lived full lives even before they had children, that we were not so important after all.

“Momma,” Christopher began slowly, “your fine, grand home in Virginia sounds nice, but we like it here. Our friends are here, everybody knows us, likes us, and I know I don’t want to move. Can’t you see Daddy’s attorney and ask him to help find a way so we can stay on, and keep our house and our furnishings?”

“Yes, Momma, please, let us stay here,” I added.

Quickly Momma was out of her chair and striding across the room. She dropped down on her knees before us, her eyes on the level with ours. “Now listen to me,” she ordered, catching my brother’s hand and mine and pressing them both against her breasts. “I have thought, and I have thought of how we can manage to stay on here, but there is no way—no way at all, because we have no money to meet the monthly bills, and I don’t have the skills to earn an adequate salary to support four children and myself as well. Look at me,” she said, throwing wide her arms, appearing vulnerable, beautiful, helpless. “Do you know what I am? I am a pretty, useless ornament who always believed she’d have a man to take care of her. I don’t know how to do anything. I can’t even type. I’m not very good with arithmetic. I can embroider beautiful needlepoint and crewelwork stitches, but that kind of thing doesn’t earn any money. You can’t live without money. It’s not love that makes the world go ’round—it’s money. And my father has more money than he knows what to do with. He has only one living heir—me! Once he cared more for me than he did for either of his sons, so it shouldn’t be difficult to win back his affection. Then he will have his attorney draw me into a new will, and I will inherit everything! He is sixty-six years old, and he is dying of heart disease. From what my mother wrote on a separate sheet of paper which my father didn’t read, your grandfather cannot possibly live more than two or three months longer at the most. That will give me plenty of time to charm him into loving me like he used to—and when he dies, his entire fortune will be mine! Mine! Ours! We will be free forever of all financial worries. Free to go anywhere we want. Free to do anything we want. Free to travel, to buy what our hearts desire—anything our hearts desire! I’m not speaking of only a million or two, but many, many millions—maybe even billions! People with that kind of money don’t even know their own net value, for it’s invested here and there, and they own this and that, including banks, airlines, hotels, department stores, shipping lines. Oh, you just don’t realize the kind of empire your grandfather controls, even now, while he’s on his last legs. He has a genius for making money. Everything he touches turns to gold.”

Her blue eyes gleamed. The sun shone through the front windows, casting diamond strands of light on her hair. Already she seemed rich beyond value. Momma, Momma, how had all of this come about only after our father died?

“Christopher, Cathy, are you listening, using your imaginations? Do you realize what a tremendous amount of money can do? The world, and everything in it is yours! You have power, influence, respect. Trust me. Soon enough I will win back my father’s heart. He’ll take one look at me, and realize instantly how all those fifteen years we’ve been separated have been such a waste. He’s old, sick, he always stays on the first floor, in a small room beyond the library, and he has nurses to take care of him night and day, and servants to wait on him hand and foot. But only your own flesh and blood means anything, and I’m all he has left, only me. Even the nurses don’t find it necessary to climb the stairs, for they have their own bath. One night, I will prepare him to meet his four grandchildren, and then I will bring you down the stairs, and into his room, and he will be charmed, enchanted by what he sees: four beautiful children who are perfect in every way—he is bound to love you, each and every one of you. Believe me, it will work out, just the way I say. I promise that whatever my father requires of me, I will do. On my life, on all I hold sacred and dear—and that is the children my love for your father made—you can believe I will soon be the heiress to a fortune beyond belief, and through me, every dream you’ve ever had will come true.”

My mouth gaped open. I was overwhelmed by her passion. I glanced at Christopher to see him staring at Momma with incredulity. Both the twins were on the soft fringes of sleep. They had heard none of this.

* * *

We were going to live in a house as big and rich as a palace.

In that palace so grand, where servants waited on you hand and foot, we would be introduced to King Midas, who would soon die, and then we would have all the money, to put the world at our feet. We were stepping into riches beyond belief! I would be just like a princess!

Yet, why didn’t I feel really happy?

“Cathy,” said Christopher, beaming on me a broad, happy smile, “you can still be a ballerina. I don’t think money can buy talent, nor can it make a good doctor out of a playboy. But, until the time comes when we have to be dedicated and serious, my, aren’t we gonna have a ball?”

* * *

I couldn’t take the sterling-silver music box with the pink ballerina inside. The music box was expensive and had been listed as something of value for “them” to claim.

I couldn’t take down the shadowboxes from the walls, or hide away the miniature dolls. There was hardly anything I could take that Daddy had given me except the small ring on my finger, with a semiprecious gem stone shaped like a heart.

And, just like Christopher said, after we were rich, our lives would be one big ball, one long, long party. That’s the way rich people lived—happily ever after as they counted their money and made their fun plans.

* * *

Fun, games, parties, riches beyond belief, a house as big as a palace, with servants who lived over a huge garage that stored away at least nine or ten expensive automobiles. Who would ever have guessed my mother came from a family like that? Why had Daddy argued with her so many times about spending money lavishly, when she could have written letters home before, and done a bit of humiliating begging?

Slowly I walked down the hall to my room, to stand before the silver music box where the pink ballerina stood in arabesque position when the lid was opened, and she could see herself in the reflecting mirror. And I heard the tinkling music play, “Whirl, ballerina, whirl . . . .”

I could steal it, if I had a place to hide it.

Good-bye, pink-and-white room with the peppermint walls. Good-bye, little white bed with the dotted-Swiss canopy that had seen me sick with measles, mumps, chicken pox.

Good-bye again to you, Daddy, for when I’m gone, I can’t picture you sitting on the side of my bed, and holding my hand, and I won’t see you coming from the bathroom with a glass of water. I really don’t want to go too much, Daddy. I’d rather stay and keep your memory close and near.

“Cathy”—Momma was at the door—“don’t just stand there and cry. A room is just a room. You’ll live in many rooms before you die, so hurry up, pack your things and the twins’ things, while I do my own packing.”

Before I died, I was going to live in a thousand rooms or more, a little voice whispered this in my ear . . . and I believed.

Truly, when I was very young, way back in the Fifties, I believed all of life would be like one long and perfect summer day. After all, it did start out that way. There’s not much I can say about our earliest childhood except that it was very good, and for that, I should be everlastingly grateful. We weren’t rich, we weren’t poor. If we lacked some necessity, I couldn’t name it; if we had luxuries, I couldn’t name those, either, without comparing what we had to what others had, and nobody had more or less in our middleclass neighborhood. In other words, short and simple, we were just ordinary, run-of-the-mill children.

Our daddy was a P.R. man for a large computer manufacturing firm located in Gladstone, Pennsylvania: population, 12,602. He was a huge success, our father, for often his boss dined with us, and bragged about the job Daddy seemed to perform so well. “It’s that all-American, wholesome, devastatingly good-looking face and charming manner that does them in. Great God in heaven, Chris, what sensible person could resist a fella like you?”

Heartily, I agreed with that. Our father was perfect. He stood six feet two, weighed 180 pounds, and his hair was thick and flaxen blond, and waved just enough to be perfect; his eyes were cerulean blue and they sparkled with laughter, with his great zest for living and having fun. His nose was straight and neither too long nor too narrow, nor too thick. He played tennis and golf like a pro and swam so much he kept a suntan all through the year. He was always dashing off on airplanes to California, to Florida, to Arizona, or to Hawaii, or even abroad on business, while we were left at home in the care of our mother.

When he came through the front door late on Friday afternoons—every Friday afternoon (he said he couldn’t bear to be separated from us for longer than five days)—even if it were raining or snowing, the sun shone when he beamed his broad, happy smile on us.

His booming greeting rang out as soon as he put down his suitcase and briefcase: “Come greet me with kisses if you love me!”

Somewhere near the front door, my brother and I would be hiding, and after he’d called out his greeting, we’d dash out from behind a chair or the sofa to crash into his wide open arms, which seized us up at once and held us close, and he warmed our lips with his kisses. Fridays—they were the best days of all, for they brought Daddy home to us again. In his suit pockets he carried small gifts for us; in his suitcases he stored the larger ones to dole out after he greeted our mother, who would hang back and wait patiently until he had done with us.

And after we had our little gifts from his pockets, Christopher and I would back off to watch Momma drift slowly forward, her lips curved in a welcoming smile that lit up our father’s eyes, and he’d take her in his arms, and stare down into her face as if he hadn’t seen her for at least a year.

On Fridays, Momma spent half the day in the beauty parlor having her hair shampooed and set and her fingernails polished, and then she’d come home to take a long bath in perfumed-oiled water. I’d perch in her dressing room, and wait to watch her emerge in a filmy negligee. She’d sit at her dressing table to meticulously apply makeup. And I, so eager to learn, drank in everything she did to turn herself from just a pretty woman into a creature so ravishingly beautiful she didn’t look real. The most amazing part of this was our father thought she didn’t wear makeup! He believed she was naturally a striking beauty.

Love was a word lavished about in our home. “Do you love me?—For I most certainly love you; did you miss me?—Are you glad I’m home?—Did you think about me when I was gone? Every night? Did you toss and turn and wish I were beside you, holding you close? For if you didn’t, Corrine, I might want to die.”

Momma knew exactly how to answer questions like these—with her eyes, with soft whispers and with kisses.

* * *

One day Christopher and I came speeding home from school with the wintery wind blowing us through the front door. “Take off your boots in the foyer,” Momma called out from the living room, where I could see her sitting before the fireplace knitting a little white sweater fit for a doll to wear. I thought it was a Christmas gift for me, for one of my dolls.

“And kick off your shoes before you come in here,” she added.

We shed our boots and heavy coats and hoods in the foyer, then raced in stockinged feet into the living room, with its plush white carpet. That pastel room, decorated to flatter our mother’s fair beauty, was off limits for us most of the time. This was our company room, our mother’s room, and never could we feel really comfortable on the apricot brocade sofa or the cut-velvet chairs. We preferred Daddy’s room, with its dark paneled walls and tough plaid sofa, where we could wallow and fight and never fear we were damaging anything.

“It’s freezing outside, Momma!” I said breathlessly as I fell at her feet, thrusting my legs toward the fire. “But the ride home on our bikes was just beautiful. All the trees are sparkled with diamond icicles, and crystal prisms on the shrubs. It’s a fairyland out there, Momma. I wouldn’t live down south where it never snows, for anything!”

Christopher did not talk about the weather and its freezing beauty. He was two years and five months my senior and he was far wiser than I; I know that now. He warmed his icy feet as I did, but he stared up at Momma’s face, a worried frown drawing his dark brows together.

I glanced up at her, too, wondering what he saw that made him show such concern. She was knitting at a fast and skilled pace, glancing from time to time at instructions.

“Momma, are you feeling all right?” he asked.

“Yes, of course,” she answered, giving him a soft, sweet smile.

“You look tired to me.”

She laid aside the tiny sweater. “I visited my doctor today,” she said, leaning forward to caress Christopher’s rosy cold cheek.

“Momma!” he cried, taking alarm. “Are you sick?”

She chuckled softly, then ran her long, slim fingers through his tousled blond curls. “Christopher Dollanganger, you know better than that. I’ve seen you looking at me with suspicious thoughts in your head.” She caught his hand, and one of mine, and placed them both on her bulging middle.

“Do you feel anything?” she asked, that secret, pleased look on her face again.

Quickly, Christopher snatched his hand away as his face turned blood-red. But I left my hand where it was, wondering, waiting.

“What do you feel, Cathy?”

Beneath my hand, under her clothes, something weird was going on. Little faint movements quivered her flesh. I lifted my head and stared up in her face, and to this day, I can still recall how lovely she looked, like a Raphael madonna.

“Momma, your lunch is moving around, or else you have gas.” Laughter made her blue eyes sparkle, and she told me to guess again.

Her voice was sweet and concerned as she told us her news. “Darlings, I’m going to have a baby in early May. In fact when I visited my doctor today, he said he heard two heartbeats. So that means I am going to have twins . . . or, God forbid, triplets. Not even your father knows this yet, so don’t tell him until I have a chance.”

Stunned, I threw Christopher a look to see how he was taking this. He seemed bemused, and still embarrassed. I looked again at her lovely firelit face. Then I jumped up, and raced for my room!

I hurled myself face down on my bed, and bawled, really let go! Babies—two or more! I was the baby! I didn’t want any little whining, crying babies coming along to take my place! I sobbed and beat at the pillows, wanting to hurt something, if not someone. Then I sat up and thought about running away.

Someone rapped softly on my closed and locked door. “Cathy,” said my mother, “may I come in and talk this over with you?”

“Go away!” I yelled. “I already hate your babies!”

Yes, I knew what was in store for me, the middle child, the one parents didn’t care about. I’d be forgotten; there’d be no more Friday gifts. Daddy would think only of Momma, of Christopher, and those hateful babies that would displace me.

* * *

My father came to me that evening, soon after he arrived home. I’d unlocked the door, just in case he wanted to see me. I stole a peek to see his face, for I loved him very much. He looked sad, and he carried a large box wrapped in silver foil, topped by a huge bow of pink satin.

“How’s my Cathy been?” he asked softly, as I peeked from beneath my arm. “You didn’t run to greet me when I came home. You haven’t said hello; you haven’t even looked at me. Cathy, it hurts when you don’t run into my arms and give me kisses.”

I didn’t say anything, but rolled over on my back to glare at him fiercely. Didn’t he know I was supposed to be his favorite all his life through? Why did he and Momma have to go and send for more children? Weren’t two enough?

He sighed, then came to sit on the edge of my bed. “You know something? This is the first time in your life you have ever glared at me like that. This is the first Friday you haven’t run to leap up into my arms. You may not believe this, but I don’t really come alive until I come home on weekends.”

Pouting, I refused to be won over. He didn’t need me now. He had his son, and now heaps of wailing babies on the way. I’d be forgotten in the multitude.

“You know something else,” he began, closely watching me, “I used to believe, perhaps foolishly, that if I came home on Fridays, and didn’t bring one single gift for you, or your brother . . . I still believed the two of you would have run for me like crazy, and welcomed me home, anyway. I believed you loved me and not my gifts. I mistakenly believed that I’d been a good father, and somehow I’d managed to win your love, and that you’d know you would always have a big place in my heart, even if your mother and I have a dozen children.” He paused, sighed, and his blue eyes darkened. “I thought my Cathy knew she would still be my very special girl, because she was my first.”

I threw him an angry, hurt look. Then I choked, “But if Momma has another girl, you’ll say the same thing to her!”

“Will I?”

“Yes,” I sobbed, aching so badly I could scream from jealousy already. “You might even love her more than you do me, ’cause she’ll be little and cuter.”

“I may love her as much, but I won’t love her more.” He held out his arms and I could resist no longer. I flung myself into his arms, and clung to him for dear life. “Ssh,” he soothed as I cried. “Don’t cry, don’t feel jealous. You won’t be loved any the less. And Cathy, real babies are much more fun than dolls. Your mother will have more than she can handle, so she’s going to depend on you to help her. When I’m away from home, I’ll feel better knowing your mother has a loving daughter who will do what she can to make life easier and better for all of us.” His warm lips pressed against my teary cheek. “Come now, open your box, and tell me what you think of what’s inside.”

First I had to smother his face with a dozen kisses and give him bear hugs to make up for the anxiety I’d put in his eyes. In the beautiful box was a silver music box made in England. The music played and a ballerina dressed in pink turned slowly around and around before a mirror. “It’s a jewel box, as well,” explained Daddy, slipping on my finger a tiny gold ring with a red stone he called a garnet. “The moment I saw that box, I knew you had to have it. And with this ring, I do vow to forever love my Cathy just a little bit more than any other daughter—as long as she never says that to anyone but herself.”

* * *

There came a sunny Tuesday in May, when Daddy was home. For two weeks Daddy had been hanging around home, waiting for those babies to show up. Momma seemed irritable, uncomfortable, and Mrs. Bertha Simpson was in our kitchen, preparing our meals, and looking at Christopher and me with a smirky face. She was our most dependable baby-sitter. She lived next door, and was always saying Momma and Daddy looked more like brother and sister than husband and wife. She was a grim, grouchy sort of person who seldom had anything nice to say about anybody. And she was cooking cabbage. I hated cabbage.

Around dinnertime, Daddy came rushing into the dining room to tell my brother and me that he was driving Momma to the hospital. “Now don’t be worried. Everything will work out fine. Mind Mrs. Simpson, and do your homework, and maybe in a few hours you’ll know if you have brothers or sisters . . . or one of each.”

He didn’t return until the next morning. He was unshaven, tired looking, his suit rumpled, but he grinned at us happily. “Take a guess! Boys or girls?”

“Boys!” chimed up Christopher, who wanted two brothers he could teach to play ball. I wanted boys, too . . . no little girl to steal Daddy’s affection from his first daughter.

“A boy and a girl,” Daddy said proudly. “The prettiest little things you ever saw. Come, put your clothes on, and I’ll drive you to see them yourselves.”

Sulkily, I went, still reluctant to look even when Daddy picked me up and held me high so I could peer through the nursery room glass at two little babies a nurse held in her arms. They were so tiny! Their heads were no bigger than small apples, and small red fists waved in the air. One was screaming like pins were sticking it.

“Ah,” sighed Daddy, kissing my cheek and hugging me close, “God has been good to me, sending me another son and daughter as perfect as my first pair.”

I thought I would hate them both, especially the loudmouthed one named Carrie, who wailed and bellowed ten times louder than the quiet one named Cory. It was nearly impossible to get a full night’s rest with the two of them across the hall from my room. And yet, as they began to grow and smile, and their eyes lit up when I came in and lifted them, something warm and motherly replaced the green in my eyes. The first thing you knew, I was racing home to see them; to play with them; to change diapers and hold nursing bottles, and burp them on my shoulder. They were more fun than dolls.

I soon learned that parents have room in their hearts for more than two children, and I had room in my heart to love them, too—even Carrie, who was just as pretty as me, and maybe more so. They grew so quickly, like weeds, said Daddy, though Momma would often look at them with anxiety, for she said they were not growing as rapidly as Christopher and I had grown. This was laid before her doctor, who quickly assured her that often twins were smaller than single births.

“See,” said Christopher, “doctors do know everything.”

Daddy looked up from the newspaper he was reading and smiled. “That’s my son the doctor talking—but nobody knows everything, Chris.”

Daddy was the only one who called my older brother Chris.

We had a funny surname, the very devil to learn to spell. Dollanganger. Just because we were all blond, flaxon haired, with fair complexions (except Daddy, with his perpetual tan), Jim Johnston, Daddy’s best friend, pinned on us a nickname, “The Dresden dolls.” He said we looked like those fancy porcelain people who grace whatnot shelves and fireplace mantels. Soon everyone in our neighborhood was calling us the Dresden dolls; certainly it was easier to say than Dollanganger.

When the twins were four, and Christopher was fourteen, and I had just turned twelve, there came a very special Friday. It was Daddy’s thirty-sixth birthday and we were having a surprise party for him. Momma looked like a fairy-tale princess with her freshly washed and set hair. Her nails gleamed with pearly polish, her long formal gown was of softest aqua color, and her knotted string of pearls swayed as she glided from here to there, setting the table in the dining room so it would look perfect for Daddy’s birthday party. His many gifts were piled high on the buffet. It was going to be a small, intimate party, just for our family and our closest friends.

“Cathy,” said Momma, throwing me a quick look, “would you mind bathing the twins again for me? I gave them both baths before their naps, but as soon as they were up, they took off for the sandbox, and now they need another bath.”

I didn’t mind. She looked far too fancy to give two dirty four-year-olds splashy baths that would ruin her hair, her nails, and her lovely dress.

“And when you finish with them, both you and Christopher jump in the tub and bathe, too, and put on that pretty new pink dress, Cathy, and curl your hair. And, Christopher, no blue jeans, please. I want you to put on a dress shirt and a tie, and wear that light blue sports jacket with your cream-colored trousers.”

“Aw, heck, Momma, I hate dressing up,” he complained, scuffing his sneakers and scowling.

“Do as I say, Christopher, for your father. You know he does a lot for you; the least you can do is make him proud of his family.”

He grouched off, leaving me to run out to the back garden and fetch the twins, who immediately began to wail. “One bath a day is enough!” screamed Carrie. “We’re already clean! Stop! We don’t like soap! We don’t like hair washings! Don’t you do that to us again, Cathy, or we’ll tell Momma!”

“Hah!” I said. “Who do you think sent me out here to clean up two filthy little monsters? Good golly, how can the two of you get so dirty so quickly?”

As soon as their naked skins hit the warm water, and the little yellow rubber ducks and rubber boats began to float, and they could splash all over me, they were content enough to be bathed, shampooed, and dressed in their very best clothes. For, after all, they were going to a party—and, after all, this was Friday, and Daddy was coming home.

First I dressed Cory in a pretty little white suit with short pants. Strangely enough, he was more apt to keep himself clean than his twin. Try as I would, I couldn’t tame down that stubborn cowlick of his. It curled over to the right, like a cute pig’s tail, and—would you believe it?—Carrie wanted her hair to do the same thing!

When I had them both dressed, and looking like dolls come alive, I turned the twins over to Christopher with stern warnings to keep an ever observant eye on them. Now it was my turn to dress up.

The twins wailed and complained while I hurriedly took a bath, washed my hair, and rolled it up on fat curlers. I peeked around the bathroom door to see Christopher trying his best to entertain them by reading to them from Mother Goose.

“Hey,” said Christopher when I came out wearing my pink dress with the fluted ruffles, “you don’t look half-bad.”

“Half-bad? Is that the best you can manage?”

“Best I can for a sister.” He glanced at his watch, slammed the picture book closed, seized the twins by their dimpled hands and cried out, “Daddy will be here any minute—hurry, Cathy!”

* * *

Five o’clock came and went, and though we waited and waited, we didn’t see our father’s green Cadillac turn into our curving drive. The invited guests sat around and tried to keep up a cheerful conversation, as Momma got up and began to pace around nervously. Usually Daddy flung open the door at four, and sometimes even sooner.

Seven o’clock, and still we were waiting.

The wonderful meal Momma had spent so much time preparing was drying out from being too long in the warming oven. Seven was the time we usually put the twins to bed, and they were growing hungry, sleepy and cross, demanding every second, “When is Daddy coming?”

Their white clothes didn’t look so virgin now. Carrie’s smoothly waved hair began to curl up and look windblown. Cory’s nose began to run, and repeatedly he wiped it on the back of his hand until I hurried over with a Kleenex to clean off his upper lip.

“Well, Corinne,” joked Jim Johnston, “I guess Chris has found himself another super-broad.”

His wife threw him an angry look for saying something so tasteless.

My stomach was growling, and I was beginning to feel as worried as Momma looked. She kept pacing back and forth, going to the wide picture window and staring out.

“Oh!” I cried, having caught sight of a car turning into our tree lined driveway, “maybe that’s Daddy coming now!”

But the car that drew to a stop before our front door was white, not green. And on the top was one of those spinning red lights. An emblem on the side of that white car read STATE POLICE.