Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

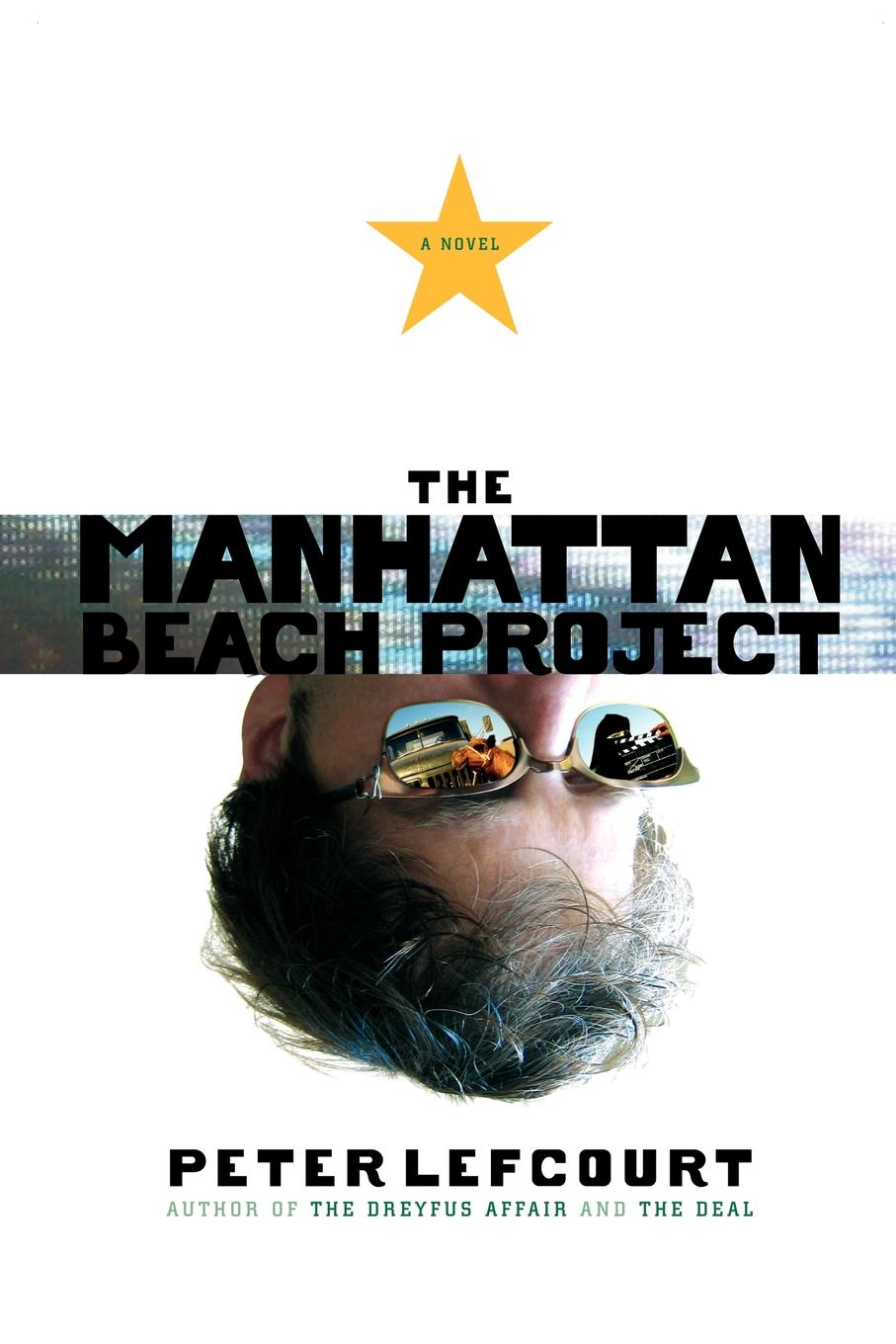

About The Book

Barely four years after winning an Oscar, Charlie has sunk into the ranks of Hollywood bottom-feeders -- reduced to living in his nephew's pool house, kiting checks and taking the bus to his weekly Debtors Anonymous meeting, where he meets a mysterious ex-CIA agent who proposes to resuscitate Charlie's foundering career -- in the beyond surreal world of reality TV.

Charlie puts his tap shoes on to sell a show about a ruthless Uzbek warlord and his family ("think The Osbournes meets The Sopranos") to a rogue division of ABC, known as ABCD, which operates out of a skunkworks in Manhattan Beach, California, and whose mandate is to develop, under top secret cover like that for the Manhattan Project, extreme reality TV shows to bolster the network's ratings.

Warlord becomes a breakout hit and results not only in causing one of America's largest entertainment conglomerates to go into full damage-control mode but also in shifting the balance of power in Central Asia and in proving that in show business it's not over till the mouse sings.

Charlie puts his tap shoes on to sell a show about a ruthless Uzbek warlord and his family ("think The Osbournes meets The Sopranos") to a rogue division of ABC, known as ABCD, which operates out of a skunkworks in Manhattan Beach, California, and whose mandate is to develop, under top secret cover like that for the Manhattan Project, extreme reality TV shows to bolster the network's ratings.

Warlord becomes a breakout hit and results not only in causing one of America's largest entertainment conglomerates to go into full damage-control mode but also in shifting the balance of power in Central Asia and in proving that in show business it's not over till the mouse sings.

Excerpt

Chapter One: Sharing

Three years, nine months and twenty-four days after winning an Academy Award for producing the best picture of the year, Charlie Berns was sitting on a folding chair in a second-floor room at the Brentwood Unitarian Church Annex listening to a woman with smeared lipstick and a bad postnasal drip tell him, and the other thirteen people in the room, that she had just charged $1,496 worth of cashmere sweaters on a VISA card she had received in the mail and failed to destroy.

"I was just a week short of eighteen months debt-free..."

The woman, who looked as if she had slept in her car with the heater on, collapsed back into a heap and began to pull compulsively on her hair.

"Thank you for sharing, Sheila," the group leader Phyllis said. "Anyone else want to share?"

She looked straight at Charlie as she said this. Charlie looked right back at her. There was no way he was going to get up there and tell this group of deadbeats that after making $2.65 million in back-end profits for producing the picture, he had let it all ride on the NASDAQ in February of 2000. That his broker at the time, Teddy Herbentin, kept calling it a market correction until the 2.65 mil dissolved into low five figures and Charlie had cashed out to pay his back property taxes. That the next picture he developed collapsed under the collective weight of four different writers, a million-plus in before the studio pulled the plug. That the book he optioned with what remained of the back-end money, an exposé on sweatshops in Honduras, turned out to be a complete fabrication by the author, who had gotten all his information off some unreliable Web sites and was being sued by the Hondurans, as well as by the publisher. That the woman he had been living with, Deidre Hearn -- a thirty-eight-year-old development executive who had been sent to shut down his Oscar-winning picture and instead wound up working on it with him -- had been killed by a faulty electric transformer on his automatic sprinkler system, electrocuted on the Fourth of July last year when she had tried to repair a broken sprinkler head and her wet hand had made contact with the exposed terminal of the transformer that his gardener had been promising to fix for months.

Nor was he going to share the fact that he was living in his nephew Lionel's pool house, driving Lionel's personal assistant's sister's car while she was recovering from periodontal surgery -- a 1989 Honda Civic with one functioning headlight -- communicating on a cell phone that he had gotten on promotion with a kited credit card and was there in this Debtors Anonymous meeting only because his debt consolidator had insisted he attend as a condition of his protecting Charlie from the dogpack of creditors that descended on his mailbox daily.

This was the third meeting he had been to, and he had yet to open his mouth, except to wolf down bagels during the after-meeting social period. He hadn't gotten past the first of the twelve steps: We admitted that we were powerless over debt -- that our lives had become unmanageable.

As far as Charlie was concerned, his problems had nothing to do with being powerless over debt: it was the debt that was making him powerless, a semantic distinction that did not seem to fall under any of the twelve steps displayed prominently on the church annex room wall. If it hadn't been for that three-year-and-counting market correction; if he had gotten a decent script of two to produce; if he hadn't become severely depressed after Deidre died trying to save his lawn; plus a few dozen other ifs, he would still be living in his 4,900 square feet in the Beverly Hills flats, driving the SEL560 and employing a small army of people to deal with his life for him.

He had gone to his debt consolidator, Xuang Duc, a Vietnamese with a green card and no-frills English, only because his creditors had started to call him at all hours at Lionel's, his last known phone number, and Lionel told him to please do something about it asap because he, Lionel, did not want to have to change his phone number.

And it was Xuang Duc who had suggested that he see a mental health professional and had furnished him with a list of people who would treat people temporarily unable to pay. When he started having suicidal thoughts, Charlie took out the list and scanned it, looking for someone convenient to Brentwood. He avoided driving to places in more remote areas of the city because he was using an expired Union 76 gas card, whose existence he had not disclosed to Xuang Duc, as he was supposed to, and which would certainly be shut down soon.

This was not the first time that Charlie Berns had considered pulling the plug. A year and a half before winning the Best Picture Oscar, he had actually hooked up a hose to the exhaust pipe of his about-to-be-repossessed Mercedes and fed it through the doggie door of his Beverly Hills house, after having taped up all the windows meticulously with gaffer's tape. It was only the fortuitous arrival of his nephew Lionel, just off the Greyhound from New Jersey, that had kept Charlie from drifting into oblivion on the fumes of his fuel-injected engine.

And it was Lionel's script based on the life of the nineteenth-century British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli that Charlie had optioned, had a drunken hack named Madison Kearney rewrite into a Middle Eastern action movie called Lev Disraeli: Freedom Fighter, got the studio to invest fifty million dollars in against domestic box office after he managed to get a black action star with a fleeting interest in Zionism to commit to the picture, which started shooting in Belgrade, cheating Tel Aviv, until the action star got kidnapped by Macedonian separatists and Charlie had to shoot the original Disraeli script on a hidden location in Yugoslavia, cheating 1870s London, without the studio's knowing where they were until it was too late and they realized they had a best-picture candidate in the beautifully produced, talky melodrama that eventually won the big one while Charlie sat in the Shrine Auditorium catatonic in his rented tuxedo barely able to make it to the stage to accept his award in front of a planetwide TV audience.

All that was water under the bridge. Though you would have thought, as Charlie often did, that the Oscar would have at least allowed him to skate for a couple of years, enjoying fat studio housekeeping deals while developing his next picture. But he hadn't counted on the new lean and mean bottom-line studio management philosophy brought on by vertical integration and balance sheet accountability, his girlfriend getting shocked to death on his front lawn, the NASDAQ's going south, or the general law of diminishing returns as he passed birthdays that progressively defined him as an endangered species in the youth-sucking ecology of the film business.

So there he was, on the second floor of the Brentwood Unitarian Church Annex, staring down the group leader, a reedy women named Phyllis who was five years into recovery after having maxed out every charge card she could get her hands on. There were only twenty minutes left before coffee and bagels, and he wasn't going to crack now.

A woman wearing aviator glasses with a Band-Aid holding them together, a Milwaukee Brewers windbreaker and sweatpants, raised her hand.

"Thank you, Wilma," Phyllis said, all the time keeping her eyes on Charlie.

"Well," said Wilma, "I finally told Carl to move out. I had six years invested in that relationship and like I said last meeting it was suffocating me I could barely breathe you have no idea..."

When the collection basket came around, Charlie contributed two dollars -- a dollar less than Phyllis suggested but, given the fact that he had seven dollars in his pocket, a generous contribution none-theless in that it amounted to a significant percentage of his net worth -- and then stiffed it when they sent the basket back around a second time to make up what they claimed they needed to cover the coffee and the bagels.

When sharing was over, Phyllis asked people to raise their hands if they were willing to be called before the next meeting, and everyone but Charlie and a guy sitting across the room from him dutifully raised their hands. He was a short, wiry guy, maybe late forties, with bleached teeth, wearing a nicely cut sport jacket, pressed slacks, Italian shoes and tinted glasses.

During coffee and bagel time this man approached Charlie and introduced himself. "Kermit Fenster," he said, violating the rule about using last names.

"How're you doing," Charlie responded.

"You're in the entertainment business, aren't you?"

Charlie flinched.

"How do I know that? I know that because I am blessed with a photographic memory for faces. I can remember someone I met at a cocktail party sixteen years ago."

"Have we met?"

"I saw you on TV. At the Academy Awards, I'm saying three, maybe four years ago. Course, you were wearing a tux at the time and had a couple of less miles on the odometer."

He took out a tin of Altoids, offered Charlie one.

"No thanks."

"I could use a twelve-step to get off this shit. Listen, I'd like to talk to you about something."

"I'm really not in the business anymore."

"Just want to pick your brain."

"Maybe next time. I've got to take off now," Charlie said, looking pointedly at the door.

Kermit Fenster took out a thick wallet and handed him a business card.

"Give me a ring when you got a moment. We'll grab a cup of coffee."

"Sure thing," said Charlie, heading for the door.

As he walked down the hall, he passed the AA meeting room next door. Through the glass he could see someone sharing. From the man's expression of excruciatingly contrite sincerity, Charlie put him between Step Four (We made a searching and fearless moral investigation of ourselves) and Step Five (We admitted to God, as we understand Him, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs).

For ten minutes Charlie sat in the Honda at an expired parking meter, keeping an eye in the rearview for the traffic gestapo vehicle while he tried to remember which ATM he could hit. The complex kiting system he had devised for his remaining credit cards involved intricate timing. One false move and it could all come tumbling down on him. He could drive back to Lionel's and review the monthly statements, but Lionel lived way up in Mandeville Canyon, ten miles up and back, and the gas gauge was to the left of E.

He riffled through his small stack of charge cards, trying to intuit which one had a little breathing room on it. Closing his eyes, he strained to visualize the name of the company to whom he wrote the check on the overdrawn City National checking account which he mailed off at the beginning of the month, the third, maybe, which would mean they got the check for the minimum amount due on the fourth or the fifth, which would mean that he was good to the end of the billing cycle, which was the seventeenth, which was two weeks ago, nine days before the due date which would be yesterday, which....His mind skidded off the rails. These computations were getting more and more complex, especially when you had four different cards working and three bank accounts.

Not only was this system perilous, it was, as Xuang Duc had pointed out, ultimately self-defeating. Kiting credit cards was like walking from one melting ice floe to another. He was paying 19.90 percent interest on the ATM advances and merely sinking deeper and deeper into the abyss. "You making banks very rich," Xuang Duc had explained. "Where else they going to get 20 percent on their money?"

Charlie tried the MasterCard in an ATM on San Vicente, inserting it like he was putting a dollar in a slot machine, and when that didn't pay off, he tried the VISA and hit it for $80. As it turned out, he needed the eighty because the Union 76 pump spit out his gas card, and he had to give them cash in advance before they turned the spigot back on. He filled the tank only one quarter full. It was indicative of his frame of mind these days that he thought a full tank of gas was an improvident investment in his future.

Charlie did a Taco Bell drive-through for their 99-cent special. As he sat eating his lunch, he considered whether he should blow off Judith, his pro bono therapist, with whom he had a three o'clock appointment. But if he did, he would have to account to Xuang Duc, to whom Judith would report his absence. If he blew off both Judith and Xuang Duc, then he'd have to account only to VISA and MasterCard.

Judith Dinkman lived in a $1.4 million bungalow south of Olympic in Baja Beverly Hills. Her office was a converted garage apartment, furnished in brightly painted IKEA colors with travel posters on the walls. His therapist greeted him at the door with her usual motherly look, her tortoiseshell glasses hanging over her ample bosom on a gold chain. They sat opposite each other, on matching director's chairs.

"So," she said, "what's happening?"

"Not a whole lot."

"Why is that?"

"There's not much going on in my life. I go to DA meetings, then I meet with my debt consolidator, then I meet with you. What kind of life is that?"

"Isn't that the question?"

"If I had a life, I could talk about it. But I don't have a life."

"That's what we need to talk about. Why don't you have a life?"

"I can't get a job."

"And why can't you get a job?"

"I can't get a job because I spend all my time going to meetings to discuss why I can't get a job."

They went around in circles like this all the time. The same questions, the same answers. He might as well phone it in.

"All right," she said, "don't come back. I mean, there's no point in doing this unless you're willing to work at it, is there?"

"Okay, you win."

"I don't win anything. This isn't about me."

0

"You're right. I'm sorry. It's just that I don't like doing this."

"You're not supposed to like it. If you like it, you're not doing it right."

He nodded, took a deep breath. It was time to share.

"So, I went to another meeting this morning. I listened to a lot of fucked-up people talking about themselves. It made me feel pretty together actually. And then afterwards this guy came up to me, said he recognized me from seeing me get the Oscar on TV. Which was very strange because that was almost four years ago and no one else in this town seems to remember it."

"What did he say?"

"He said he wanted to talk to me about something."

"What did you do?"

"Took his card."

"Are you going to talk to him?"

"I don't know. I mean, he doesn't look like Michael J. Anthony."

"Who?"

"Michael J. Anthony. He was the guy who gave away the money on The Millionaire. He worked for John Beresford Tipton, and he would go up to this stranger that they had preselected and tell that person that his name was Michael J. Anthony and that he was going to give him a million dollars -- was this before your time?"

"Yes."

"Because if I had a million dollars I wouldn't be having this problem."

"Charlie, it's not about the money. We're past that."

Every week in DA they said it was not about the money. Xuang Duc had said that to him, as well, at their first meeting in the debt consolidator's small office in Glendale. Charlie had sat across the desk as the Vietnamese with the pocket protector and the wrinkle-free slacks explained to him, in his erratic, machine-gun English, that debt was only conquerable by behavior modification.

He had asked Charlie to bring all his bills, credit cards and bank statements to their first meeting. Charlie had held four of his sixteen cards out, plus three of his seven bank accounts. Xuang Duc played the calculator like a concert pianist, totaling up Charlie's outstanding debts, calculating the interest, then entering it all into a program on his computer that calculated the one monthly charge he would have to pay the company that Xuang Duc worked for in lieu of all the other debts. He printed it out and handed it to Charlie. It was an unsettling number.

"It look big only because it's total of all your obligations. But you add them up, you paying a lot more. Look at that number. Column six."

Charlie looked at that number.

"You saving 16.8 percent on the face, 9.3 percent after you pay us. Plus you don't have people calling you all hours, and you get credit rating clean."

Charlie wrote a check for the initial consultation and signed a number of forms he didn't bother reading, which enabled Xuang Duc's company to make monthly automatic withdrawals from Charlie's bank account.

The withdrawals came on the tenth of the month, another variable he would have to keep in consideration for his complex juggling of funds. He'd ATM on the ninth and make a cash deposit at the bank to cover the automatic withdrawal --

"Charlie, did you hear me?"

Judith's voice pulled his attention back to Baja Beverly Hills.

"What was that?"

"I said that we both know that this is not just about money. So are we going to talk about what it's about, or just keep going around in circles?"

"How come you're doing this for nothing?"

"We're not here to talk about me."

"Well, yeah, but I think it's strange that you're not getting paid."

"All right. That's it. We're finished."

She rose from her seat like a large wave, filling the space with her shapeless navy blue dress. "Get out."

"You're throwing me out?'

"You bet."

Charlie looked up at her hovering over him, her eyes moist with anger.

"You don't want me to come on Thursday?"

"Nope."

"Next Tuesday?"

"No."

"So this is what -- tough love?"

"There's no love at all in this. Adios, Charlie."

Charlie drove west on Sunset, through the Beverly Hills flats, feeling a little shaky. He had just been fired by his therapist. Frankly, he didn't blame her. He was a pain in the ass, a charity-case pain in the ass, no less.

Well, there went Tuesday and Thursday afternoons. He'd think of something else to do with the time. He could always join another twelve-step. There were meetings every day of the week. There was a Gamblers Anonymous that met Tuesdays and Thursdays in Santa Monica. He'd been in the movie business. He could relate to that.

On a whim, he turned right onto Alpine and pulled up in front of his old house. The bank had foreclosed for a song. Since Charlie had about a dollar fifty worth of equity left in the house, having refied it till it bled, he let it go without a struggle.

The house had been remodeled by the new owner. What had once been a nominally Mediterranean house, stucco and Spanish tile roof, had been transformed into a dark blue French chateau, with faux Norman shutters, crenellated roof and a marble statue of a Charles de Gaulle in full dress uniform with a képi on his head on the front lawn.

Charlie's throat caught as he looked at the front lawn, planted with some sort of completely un-Normanlike succulents. They had ripped up his lawn -- the lawn that Deidre had given her life to try to save.

Deidre. He could have talked about her with Judith. Deidre would never have let things come to this. She had no patience for his self-pity. "Charlie, you're full of shit," she would tell him. Lovingly. Gently. With that little cracked smile of hers, that smile that he had loved more than anything he could remember. As he sat there in the Honda and stared at the lawn, the very lawn that she had been trying to revive when she stuck her wet hands into the exposed circuitry of the broken transformer, small warm tears clouded over his vision.

The small warm tears became warmer and less small. It wasn't long before he was bawling loudly in the front seat of the car, undoubtedly a strange sight to anyone who may have been looking out the window of the navy blue chateau because somebody inside the house had, in fact, been looking out the stained-glass front window and, seeing a strange man crying loudly in a beat-up Honda in front of their house, called the Beverly Hills police.

Minutes later a tall blond motorcycle cop was shining a flashlight in his eyes.

"You want to step outside the vehicle, sir."

When Charlie did not react immediately, the storm trooper moved closer, his hand on his weapon, and repeated the command.

Charlie stepped out of the vehicle. The cop, whose name, appropriately, was Heimler, asked him for identification.

Charlie produced his driver's license, which still had the Alpine Drive address. Heimler examined it, looked at Charlie, looked at the house and the house number, and said, "Do you live here?"

"No."

"How come your driver's license has this address?"

"I used to live here."

"What are you doing here now?"

"Reminiscing."

Heimler curled his lip, unhappy with this answer.

"I lost the house to the bank," Charlie explained. "I didn't have enough in to refie again so I just let them take it. Anyway, I'm in Debtors Anonymous, so I'm working on the problem. I was on my way home from my therapist when I passed the street and thought I'd have a look at the house. It used to be Mediterranean, believe it or not."

"Where do you live now?"

"Top of Mandeville Canyon. With my nephew Lionel. Actually, in his pool house. You see, I gave him his first job, four years ago. He wrote the script for Dizzy and Will. Won Best Picture. You happen to see it?"

The cop shook his head, handed Charlie back his driver's license and said, "You need to get your address changed on your driver's license."

"Sure," said Charlie. "I've got a lot of time on my hands."

Sergeant Heimler stood in front of the house, arms folded, and watched as Charlie got in his car, did a U-turn, and headed back to Sunset. He waited five more minutes to make sure he didn't return.

Later that night, as Charlie sat watching CSI: El Paso in the pool house beside the Olympic-length lap pool behind Lionel's sprawling Greek Revival home on the top of Mandeville Canyon, his nephew slid the glass door open and walked in. Charlie looked up and saw his sister Bea's son wearing a cashmere sweater, designer jeans and socks. Lionel had a personal shopper, as well as a personal assistant, a workout coach, manager, agent, lawyer, accountant, stockbroker, decorator, pool man, gardener, housekeeper, dog walker and closet organizer. Charlie eyeballed his nephew's above-the-line expenses for this platoon of people at a couple of hundred thou a year easy.

Lionel Traven, né Travitz, was pushing twenty-five and, in a large part due to his having written Charlie's Oscar-winning movie four years ago, was an A-Plus List screenwriter. He was so hot that he had five different scripts stockpiled at the moment -- all of them high-profile projects with major talent attached. The amount of money potentially represented by these jobs was enough to present challenging tax problems, causing him to purchase a share of a negative cash-flow medical building in Costa Mesa and a sizable position in some very volatile Indonesian rubber stock futures.

"Hey, Uncle Charlie. How're you doing?"

"All right, Lionel."

"Got a moment?"

Charlie hit the "mute" button on the TV just as Jason Priestley stuck the coyote excrement under the electron microscope. Lionel put his hands in his pockets, flexed his jaws uncomfortably, which signaled to Charlie that he was about to hear bad news.

"Uh...here's the thing. Shari?"

Charlie nodded. This was the way that you had a conversation with Lionel. He would utter a series or short interrogative phrases, and you would nod until he continued.

"She's been living with me?"

Shari had been hired to organize Lionel's closets and had managed to parlay this into a live-in position. Lionel's closets all looked like file cabinets. After alphabetizing his spice rack, she had color-coordinated his sweater drawer.

"Well, she's thinking of branching out into general organization?"

Nod.

"You know, help people get organized? Arrange their offices? Their schedules? Their priorities?"

Nod.

"So she kind of would like to have an office to work out of? You know what I mean?"

Nod.

"And she thought that the pool house would be perfect?"

Nod.

"So...you know, we were kind of thinking what your plans were?"

"Plans?" he uttered, batting the ball back to Lionel's side of the court.

"Uh-huh. Like...are you going to be like moving out soon?"

"Moving out?"

"Uh-huh..."

"Where?"

"Like to an apartment somewhere or a house?"

"Oh."

A protracted moment of strained silence passed. Charlie considered pointing out to his nephew that, unlike Shari, he, Charlie, was family, that it was in a large part thanks to him, Charlie, that Lionel now owned part of a negative cash-flow medical building in Costa Mesa.

"Maybe you could like find a place in the Oakwood Apartments? They're, like, convenient to the studios? For your meetings?"

Charlie hadn't had a meeting at a studio in months. The only meetings he went to now were meetings at which people got up and spilled their guts. The Oakwood Apartments were furnished lodgings, basically Embassy Suites with Internet access and optional maid service. They were expensive, depressing, full of people getting divorced or out from the East Coast for a month or two. Charlie couldn't make a week's rent, let alone a month's.

"When does Shari need the space by?"

"Like asap?"

"All right. I'll look for a place."

"Great? Oh yeah, and Rita's off the painkiller for her gum surgery?"

"Good."

"So she's going to need her car back?"

"Right."

"See you later?"

And his nephew gave him a cheerful wave and retreated to the main house. Charlie kept the "mute" button on and stared blankly at the screen. Dana Delany was taking off her lab coat, looking a little chunky in a pair of baggy woolen slacks. Charlie would have fired the wardrobe mistress for letting Dana Delany wear those slacks.

He leaned back on the couch and closed his eyes. Very slowly he exhaled, as if he were trying to conserve his breath. He hadn't thought that things could get any worse. But they just had.

He was now not only broke and carless. He was homeless.

Copyright © 2005 by Chiaroscuro Productions

Three years, nine months and twenty-four days after winning an Academy Award for producing the best picture of the year, Charlie Berns was sitting on a folding chair in a second-floor room at the Brentwood Unitarian Church Annex listening to a woman with smeared lipstick and a bad postnasal drip tell him, and the other thirteen people in the room, that she had just charged $1,496 worth of cashmere sweaters on a VISA card she had received in the mail and failed to destroy.

"I was just a week short of eighteen months debt-free..."

The woman, who looked as if she had slept in her car with the heater on, collapsed back into a heap and began to pull compulsively on her hair.

"Thank you for sharing, Sheila," the group leader Phyllis said. "Anyone else want to share?"

She looked straight at Charlie as she said this. Charlie looked right back at her. There was no way he was going to get up there and tell this group of deadbeats that after making $2.65 million in back-end profits for producing the picture, he had let it all ride on the NASDAQ in February of 2000. That his broker at the time, Teddy Herbentin, kept calling it a market correction until the 2.65 mil dissolved into low five figures and Charlie had cashed out to pay his back property taxes. That the next picture he developed collapsed under the collective weight of four different writers, a million-plus in before the studio pulled the plug. That the book he optioned with what remained of the back-end money, an exposé on sweatshops in Honduras, turned out to be a complete fabrication by the author, who had gotten all his information off some unreliable Web sites and was being sued by the Hondurans, as well as by the publisher. That the woman he had been living with, Deidre Hearn -- a thirty-eight-year-old development executive who had been sent to shut down his Oscar-winning picture and instead wound up working on it with him -- had been killed by a faulty electric transformer on his automatic sprinkler system, electrocuted on the Fourth of July last year when she had tried to repair a broken sprinkler head and her wet hand had made contact with the exposed terminal of the transformer that his gardener had been promising to fix for months.

Nor was he going to share the fact that he was living in his nephew Lionel's pool house, driving Lionel's personal assistant's sister's car while she was recovering from periodontal surgery -- a 1989 Honda Civic with one functioning headlight -- communicating on a cell phone that he had gotten on promotion with a kited credit card and was there in this Debtors Anonymous meeting only because his debt consolidator had insisted he attend as a condition of his protecting Charlie from the dogpack of creditors that descended on his mailbox daily.

This was the third meeting he had been to, and he had yet to open his mouth, except to wolf down bagels during the after-meeting social period. He hadn't gotten past the first of the twelve steps: We admitted that we were powerless over debt -- that our lives had become unmanageable.

As far as Charlie was concerned, his problems had nothing to do with being powerless over debt: it was the debt that was making him powerless, a semantic distinction that did not seem to fall under any of the twelve steps displayed prominently on the church annex room wall. If it hadn't been for that three-year-and-counting market correction; if he had gotten a decent script of two to produce; if he hadn't become severely depressed after Deidre died trying to save his lawn; plus a few dozen other ifs, he would still be living in his 4,900 square feet in the Beverly Hills flats, driving the SEL560 and employing a small army of people to deal with his life for him.

He had gone to his debt consolidator, Xuang Duc, a Vietnamese with a green card and no-frills English, only because his creditors had started to call him at all hours at Lionel's, his last known phone number, and Lionel told him to please do something about it asap because he, Lionel, did not want to have to change his phone number.

And it was Xuang Duc who had suggested that he see a mental health professional and had furnished him with a list of people who would treat people temporarily unable to pay. When he started having suicidal thoughts, Charlie took out the list and scanned it, looking for someone convenient to Brentwood. He avoided driving to places in more remote areas of the city because he was using an expired Union 76 gas card, whose existence he had not disclosed to Xuang Duc, as he was supposed to, and which would certainly be shut down soon.

This was not the first time that Charlie Berns had considered pulling the plug. A year and a half before winning the Best Picture Oscar, he had actually hooked up a hose to the exhaust pipe of his about-to-be-repossessed Mercedes and fed it through the doggie door of his Beverly Hills house, after having taped up all the windows meticulously with gaffer's tape. It was only the fortuitous arrival of his nephew Lionel, just off the Greyhound from New Jersey, that had kept Charlie from drifting into oblivion on the fumes of his fuel-injected engine.

And it was Lionel's script based on the life of the nineteenth-century British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli that Charlie had optioned, had a drunken hack named Madison Kearney rewrite into a Middle Eastern action movie called Lev Disraeli: Freedom Fighter, got the studio to invest fifty million dollars in against domestic box office after he managed to get a black action star with a fleeting interest in Zionism to commit to the picture, which started shooting in Belgrade, cheating Tel Aviv, until the action star got kidnapped by Macedonian separatists and Charlie had to shoot the original Disraeli script on a hidden location in Yugoslavia, cheating 1870s London, without the studio's knowing where they were until it was too late and they realized they had a best-picture candidate in the beautifully produced, talky melodrama that eventually won the big one while Charlie sat in the Shrine Auditorium catatonic in his rented tuxedo barely able to make it to the stage to accept his award in front of a planetwide TV audience.

All that was water under the bridge. Though you would have thought, as Charlie often did, that the Oscar would have at least allowed him to skate for a couple of years, enjoying fat studio housekeeping deals while developing his next picture. But he hadn't counted on the new lean and mean bottom-line studio management philosophy brought on by vertical integration and balance sheet accountability, his girlfriend getting shocked to death on his front lawn, the NASDAQ's going south, or the general law of diminishing returns as he passed birthdays that progressively defined him as an endangered species in the youth-sucking ecology of the film business.

So there he was, on the second floor of the Brentwood Unitarian Church Annex, staring down the group leader, a reedy women named Phyllis who was five years into recovery after having maxed out every charge card she could get her hands on. There were only twenty minutes left before coffee and bagels, and he wasn't going to crack now.

A woman wearing aviator glasses with a Band-Aid holding them together, a Milwaukee Brewers windbreaker and sweatpants, raised her hand.

"Thank you, Wilma," Phyllis said, all the time keeping her eyes on Charlie.

"Well," said Wilma, "I finally told Carl to move out. I had six years invested in that relationship and like I said last meeting it was suffocating me I could barely breathe you have no idea..."

When the collection basket came around, Charlie contributed two dollars -- a dollar less than Phyllis suggested but, given the fact that he had seven dollars in his pocket, a generous contribution none-theless in that it amounted to a significant percentage of his net worth -- and then stiffed it when they sent the basket back around a second time to make up what they claimed they needed to cover the coffee and the bagels.

When sharing was over, Phyllis asked people to raise their hands if they were willing to be called before the next meeting, and everyone but Charlie and a guy sitting across the room from him dutifully raised their hands. He was a short, wiry guy, maybe late forties, with bleached teeth, wearing a nicely cut sport jacket, pressed slacks, Italian shoes and tinted glasses.

During coffee and bagel time this man approached Charlie and introduced himself. "Kermit Fenster," he said, violating the rule about using last names.

"How're you doing," Charlie responded.

"You're in the entertainment business, aren't you?"

Charlie flinched.

"How do I know that? I know that because I am blessed with a photographic memory for faces. I can remember someone I met at a cocktail party sixteen years ago."

"Have we met?"

"I saw you on TV. At the Academy Awards, I'm saying three, maybe four years ago. Course, you were wearing a tux at the time and had a couple of less miles on the odometer."

He took out a tin of Altoids, offered Charlie one.

"No thanks."

"I could use a twelve-step to get off this shit. Listen, I'd like to talk to you about something."

"I'm really not in the business anymore."

"Just want to pick your brain."

"Maybe next time. I've got to take off now," Charlie said, looking pointedly at the door.

Kermit Fenster took out a thick wallet and handed him a business card.

"Give me a ring when you got a moment. We'll grab a cup of coffee."

"Sure thing," said Charlie, heading for the door.

As he walked down the hall, he passed the AA meeting room next door. Through the glass he could see someone sharing. From the man's expression of excruciatingly contrite sincerity, Charlie put him between Step Four (We made a searching and fearless moral investigation of ourselves) and Step Five (We admitted to God, as we understand Him, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs).

For ten minutes Charlie sat in the Honda at an expired parking meter, keeping an eye in the rearview for the traffic gestapo vehicle while he tried to remember which ATM he could hit. The complex kiting system he had devised for his remaining credit cards involved intricate timing. One false move and it could all come tumbling down on him. He could drive back to Lionel's and review the monthly statements, but Lionel lived way up in Mandeville Canyon, ten miles up and back, and the gas gauge was to the left of E.

He riffled through his small stack of charge cards, trying to intuit which one had a little breathing room on it. Closing his eyes, he strained to visualize the name of the company to whom he wrote the check on the overdrawn City National checking account which he mailed off at the beginning of the month, the third, maybe, which would mean they got the check for the minimum amount due on the fourth or the fifth, which would mean that he was good to the end of the billing cycle, which was the seventeenth, which was two weeks ago, nine days before the due date which would be yesterday, which....His mind skidded off the rails. These computations were getting more and more complex, especially when you had four different cards working and three bank accounts.

Not only was this system perilous, it was, as Xuang Duc had pointed out, ultimately self-defeating. Kiting credit cards was like walking from one melting ice floe to another. He was paying 19.90 percent interest on the ATM advances and merely sinking deeper and deeper into the abyss. "You making banks very rich," Xuang Duc had explained. "Where else they going to get 20 percent on their money?"

Charlie tried the MasterCard in an ATM on San Vicente, inserting it like he was putting a dollar in a slot machine, and when that didn't pay off, he tried the VISA and hit it for $80. As it turned out, he needed the eighty because the Union 76 pump spit out his gas card, and he had to give them cash in advance before they turned the spigot back on. He filled the tank only one quarter full. It was indicative of his frame of mind these days that he thought a full tank of gas was an improvident investment in his future.

Charlie did a Taco Bell drive-through for their 99-cent special. As he sat eating his lunch, he considered whether he should blow off Judith, his pro bono therapist, with whom he had a three o'clock appointment. But if he did, he would have to account to Xuang Duc, to whom Judith would report his absence. If he blew off both Judith and Xuang Duc, then he'd have to account only to VISA and MasterCard.

Judith Dinkman lived in a $1.4 million bungalow south of Olympic in Baja Beverly Hills. Her office was a converted garage apartment, furnished in brightly painted IKEA colors with travel posters on the walls. His therapist greeted him at the door with her usual motherly look, her tortoiseshell glasses hanging over her ample bosom on a gold chain. They sat opposite each other, on matching director's chairs.

"So," she said, "what's happening?"

"Not a whole lot."

"Why is that?"

"There's not much going on in my life. I go to DA meetings, then I meet with my debt consolidator, then I meet with you. What kind of life is that?"

"Isn't that the question?"

"If I had a life, I could talk about it. But I don't have a life."

"That's what we need to talk about. Why don't you have a life?"

"I can't get a job."

"And why can't you get a job?"

"I can't get a job because I spend all my time going to meetings to discuss why I can't get a job."

They went around in circles like this all the time. The same questions, the same answers. He might as well phone it in.

"All right," she said, "don't come back. I mean, there's no point in doing this unless you're willing to work at it, is there?"

"Okay, you win."

"I don't win anything. This isn't about me."

0

"You're right. I'm sorry. It's just that I don't like doing this."

"You're not supposed to like it. If you like it, you're not doing it right."

He nodded, took a deep breath. It was time to share.

"So, I went to another meeting this morning. I listened to a lot of fucked-up people talking about themselves. It made me feel pretty together actually. And then afterwards this guy came up to me, said he recognized me from seeing me get the Oscar on TV. Which was very strange because that was almost four years ago and no one else in this town seems to remember it."

"What did he say?"

"He said he wanted to talk to me about something."

"What did you do?"

"Took his card."

"Are you going to talk to him?"

"I don't know. I mean, he doesn't look like Michael J. Anthony."

"Who?"

"Michael J. Anthony. He was the guy who gave away the money on The Millionaire. He worked for John Beresford Tipton, and he would go up to this stranger that they had preselected and tell that person that his name was Michael J. Anthony and that he was going to give him a million dollars -- was this before your time?"

"Yes."

"Because if I had a million dollars I wouldn't be having this problem."

"Charlie, it's not about the money. We're past that."

Every week in DA they said it was not about the money. Xuang Duc had said that to him, as well, at their first meeting in the debt consolidator's small office in Glendale. Charlie had sat across the desk as the Vietnamese with the pocket protector and the wrinkle-free slacks explained to him, in his erratic, machine-gun English, that debt was only conquerable by behavior modification.

He had asked Charlie to bring all his bills, credit cards and bank statements to their first meeting. Charlie had held four of his sixteen cards out, plus three of his seven bank accounts. Xuang Duc played the calculator like a concert pianist, totaling up Charlie's outstanding debts, calculating the interest, then entering it all into a program on his computer that calculated the one monthly charge he would have to pay the company that Xuang Duc worked for in lieu of all the other debts. He printed it out and handed it to Charlie. It was an unsettling number.

"It look big only because it's total of all your obligations. But you add them up, you paying a lot more. Look at that number. Column six."

Charlie looked at that number.

"You saving 16.8 percent on the face, 9.3 percent after you pay us. Plus you don't have people calling you all hours, and you get credit rating clean."

Charlie wrote a check for the initial consultation and signed a number of forms he didn't bother reading, which enabled Xuang Duc's company to make monthly automatic withdrawals from Charlie's bank account.

The withdrawals came on the tenth of the month, another variable he would have to keep in consideration for his complex juggling of funds. He'd ATM on the ninth and make a cash deposit at the bank to cover the automatic withdrawal --

"Charlie, did you hear me?"

Judith's voice pulled his attention back to Baja Beverly Hills.

"What was that?"

"I said that we both know that this is not just about money. So are we going to talk about what it's about, or just keep going around in circles?"

"How come you're doing this for nothing?"

"We're not here to talk about me."

"Well, yeah, but I think it's strange that you're not getting paid."

"All right. That's it. We're finished."

She rose from her seat like a large wave, filling the space with her shapeless navy blue dress. "Get out."

"You're throwing me out?'

"You bet."

Charlie looked up at her hovering over him, her eyes moist with anger.

"You don't want me to come on Thursday?"

"Nope."

"Next Tuesday?"

"No."

"So this is what -- tough love?"

"There's no love at all in this. Adios, Charlie."

Charlie drove west on Sunset, through the Beverly Hills flats, feeling a little shaky. He had just been fired by his therapist. Frankly, he didn't blame her. He was a pain in the ass, a charity-case pain in the ass, no less.

Well, there went Tuesday and Thursday afternoons. He'd think of something else to do with the time. He could always join another twelve-step. There were meetings every day of the week. There was a Gamblers Anonymous that met Tuesdays and Thursdays in Santa Monica. He'd been in the movie business. He could relate to that.

On a whim, he turned right onto Alpine and pulled up in front of his old house. The bank had foreclosed for a song. Since Charlie had about a dollar fifty worth of equity left in the house, having refied it till it bled, he let it go without a struggle.

The house had been remodeled by the new owner. What had once been a nominally Mediterranean house, stucco and Spanish tile roof, had been transformed into a dark blue French chateau, with faux Norman shutters, crenellated roof and a marble statue of a Charles de Gaulle in full dress uniform with a képi on his head on the front lawn.

Charlie's throat caught as he looked at the front lawn, planted with some sort of completely un-Normanlike succulents. They had ripped up his lawn -- the lawn that Deidre had given her life to try to save.

Deidre. He could have talked about her with Judith. Deidre would never have let things come to this. She had no patience for his self-pity. "Charlie, you're full of shit," she would tell him. Lovingly. Gently. With that little cracked smile of hers, that smile that he had loved more than anything he could remember. As he sat there in the Honda and stared at the lawn, the very lawn that she had been trying to revive when she stuck her wet hands into the exposed circuitry of the broken transformer, small warm tears clouded over his vision.

The small warm tears became warmer and less small. It wasn't long before he was bawling loudly in the front seat of the car, undoubtedly a strange sight to anyone who may have been looking out the window of the navy blue chateau because somebody inside the house had, in fact, been looking out the stained-glass front window and, seeing a strange man crying loudly in a beat-up Honda in front of their house, called the Beverly Hills police.

Minutes later a tall blond motorcycle cop was shining a flashlight in his eyes.

"You want to step outside the vehicle, sir."

When Charlie did not react immediately, the storm trooper moved closer, his hand on his weapon, and repeated the command.

Charlie stepped out of the vehicle. The cop, whose name, appropriately, was Heimler, asked him for identification.

Charlie produced his driver's license, which still had the Alpine Drive address. Heimler examined it, looked at Charlie, looked at the house and the house number, and said, "Do you live here?"

"No."

"How come your driver's license has this address?"

"I used to live here."

"What are you doing here now?"

"Reminiscing."

Heimler curled his lip, unhappy with this answer.

"I lost the house to the bank," Charlie explained. "I didn't have enough in to refie again so I just let them take it. Anyway, I'm in Debtors Anonymous, so I'm working on the problem. I was on my way home from my therapist when I passed the street and thought I'd have a look at the house. It used to be Mediterranean, believe it or not."

"Where do you live now?"

"Top of Mandeville Canyon. With my nephew Lionel. Actually, in his pool house. You see, I gave him his first job, four years ago. He wrote the script for Dizzy and Will. Won Best Picture. You happen to see it?"

The cop shook his head, handed Charlie back his driver's license and said, "You need to get your address changed on your driver's license."

"Sure," said Charlie. "I've got a lot of time on my hands."

Sergeant Heimler stood in front of the house, arms folded, and watched as Charlie got in his car, did a U-turn, and headed back to Sunset. He waited five more minutes to make sure he didn't return.

Later that night, as Charlie sat watching CSI: El Paso in the pool house beside the Olympic-length lap pool behind Lionel's sprawling Greek Revival home on the top of Mandeville Canyon, his nephew slid the glass door open and walked in. Charlie looked up and saw his sister Bea's son wearing a cashmere sweater, designer jeans and socks. Lionel had a personal shopper, as well as a personal assistant, a workout coach, manager, agent, lawyer, accountant, stockbroker, decorator, pool man, gardener, housekeeper, dog walker and closet organizer. Charlie eyeballed his nephew's above-the-line expenses for this platoon of people at a couple of hundred thou a year easy.

Lionel Traven, né Travitz, was pushing twenty-five and, in a large part due to his having written Charlie's Oscar-winning movie four years ago, was an A-Plus List screenwriter. He was so hot that he had five different scripts stockpiled at the moment -- all of them high-profile projects with major talent attached. The amount of money potentially represented by these jobs was enough to present challenging tax problems, causing him to purchase a share of a negative cash-flow medical building in Costa Mesa and a sizable position in some very volatile Indonesian rubber stock futures.

"Hey, Uncle Charlie. How're you doing?"

"All right, Lionel."

"Got a moment?"

Charlie hit the "mute" button on the TV just as Jason Priestley stuck the coyote excrement under the electron microscope. Lionel put his hands in his pockets, flexed his jaws uncomfortably, which signaled to Charlie that he was about to hear bad news.

"Uh...here's the thing. Shari?"

Charlie nodded. This was the way that you had a conversation with Lionel. He would utter a series or short interrogative phrases, and you would nod until he continued.

"She's been living with me?"

Shari had been hired to organize Lionel's closets and had managed to parlay this into a live-in position. Lionel's closets all looked like file cabinets. After alphabetizing his spice rack, she had color-coordinated his sweater drawer.

"Well, she's thinking of branching out into general organization?"

Nod.

"You know, help people get organized? Arrange their offices? Their schedules? Their priorities?"

Nod.

"So she kind of would like to have an office to work out of? You know what I mean?"

Nod.

"And she thought that the pool house would be perfect?"

Nod.

"So...you know, we were kind of thinking what your plans were?"

"Plans?" he uttered, batting the ball back to Lionel's side of the court.

"Uh-huh. Like...are you going to be like moving out soon?"

"Moving out?"

"Uh-huh..."

"Where?"

"Like to an apartment somewhere or a house?"

"Oh."

A protracted moment of strained silence passed. Charlie considered pointing out to his nephew that, unlike Shari, he, Charlie, was family, that it was in a large part thanks to him, Charlie, that Lionel now owned part of a negative cash-flow medical building in Costa Mesa.

"Maybe you could like find a place in the Oakwood Apartments? They're, like, convenient to the studios? For your meetings?"

Charlie hadn't had a meeting at a studio in months. The only meetings he went to now were meetings at which people got up and spilled their guts. The Oakwood Apartments were furnished lodgings, basically Embassy Suites with Internet access and optional maid service. They were expensive, depressing, full of people getting divorced or out from the East Coast for a month or two. Charlie couldn't make a week's rent, let alone a month's.

"When does Shari need the space by?"

"Like asap?"

"All right. I'll look for a place."

"Great? Oh yeah, and Rita's off the painkiller for her gum surgery?"

"Good."

"So she's going to need her car back?"

"Right."

"See you later?"

And his nephew gave him a cheerful wave and retreated to the main house. Charlie kept the "mute" button on and stared blankly at the screen. Dana Delany was taking off her lab coat, looking a little chunky in a pair of baggy woolen slacks. Charlie would have fired the wardrobe mistress for letting Dana Delany wear those slacks.

He leaned back on the couch and closed his eyes. Very slowly he exhaled, as if he were trying to conserve his breath. He hadn't thought that things could get any worse. But they just had.

He was now not only broke and carless. He was homeless.

Copyright © 2005 by Chiaroscuro Productions

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (August 13, 2007)

- Length: 352 pages

- ISBN13: 9781416572763

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Manhattan Beach Project Trade Paperback 9781416572763(0.1 MB)

- Author Photo (jpg): Peter Lefcourt Photo Credit:(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit