Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace

A Brilliant Young Man Who Left Newark for the Ivy League

Table of Contents

About The Book

*Named a Best Book of the Year by The New York Times Book Review, Entertainment Weekly, and more* The New York Times bestselling account of a young African-American man who escaped Newark, NJ, to attend Yale, but still faced the dangers of the streets when he returned is, “nuanced and shattering” (People) and “mesmeric” (The New York Times Book Review).

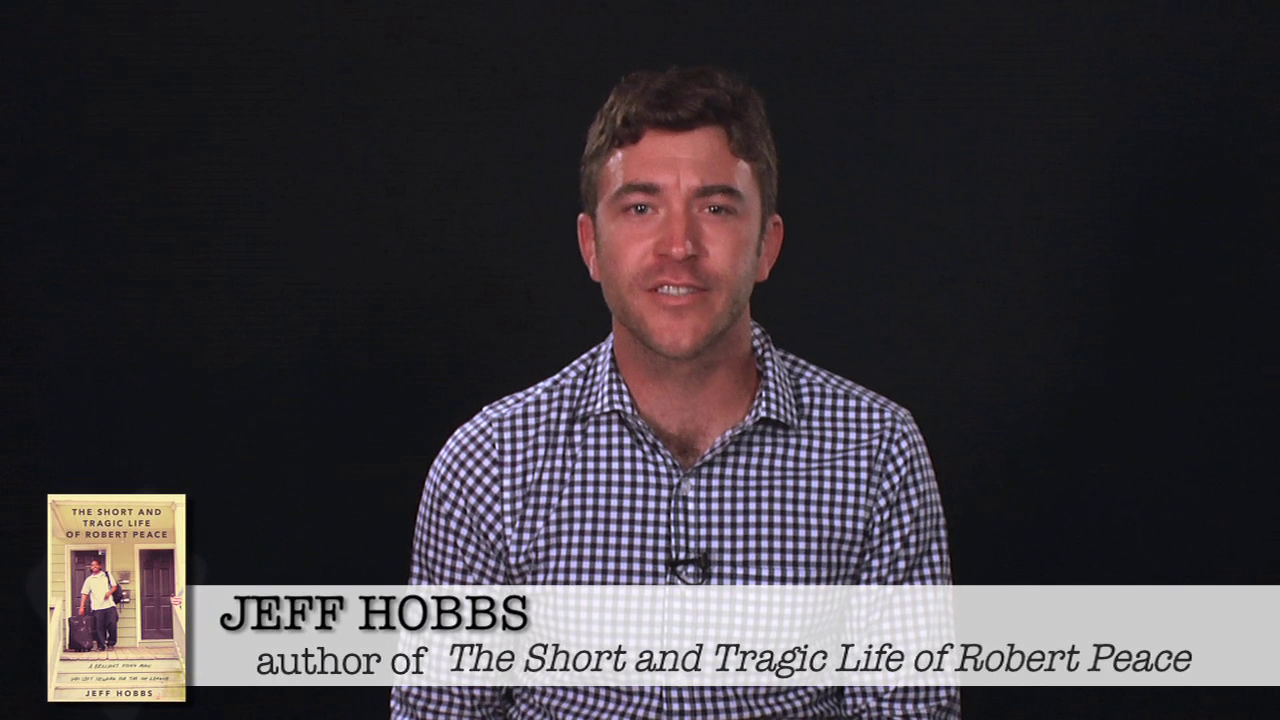

When author Jeff Hobbs arrived at Yale University, he became fast friends with the man who would be his college roommate for four years, Robert Peace. Robert’s life was rough from the beginning in the crime-ridden streets of Newark in the 1980s, with his father in jail and his mother earning less than $15,000 a year. But Robert was a brilliant student, and it was supposed to get easier when he was accepted to Yale, where he studied molecular biochemistry and biophysics. But it didn’t get easier. Robert carried with him the difficult dual nature of his existence, trying to fit in at Yale, and at home on breaks.

A compelling and honest portrait of Robert’s relationships—with his struggling mother, with his incarcerated father, with his teachers and friends—The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace encompasses the most enduring conflicts in America: race, class, drugs, community, imprisonment, education, family, friendship, and love. It’s about the collision of two fiercely insular worlds—the ivy-covered campus of Yale University and the slums of Newark, New Jersey, and the difficulty of going from one to the other and then back again. It’s about trying to live a decent life in America. But most all this “fresh, compelling” (The Washington Post) story is about the tragic life of one singular brilliant young man. His end, a violent one, is heartbreaking and powerful and “a haunting American tragedy for our times” (Entertainment Weekly).

Reading Group Guide

Get a FREE ebook by joining our mailing list today! Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

Introduction

When Jeff Hobbs arrived at Yale University, he became fast friends with the man who would be his college roommate for four years, Robert Peace. Rob’s life was rough from the beginning in the crime-ridden streets of Newark in the 1980s, with his father in jail and his mother barely scraping by as a cafeteria worker. But Rob was a brilliant student, and everything was supposed to get easier when he was accepted to Yale. But nothing got easier. Rob carried with him the difficult dual nature of his existence, “fronting” at Yale and at home.

As Jeff pieces together Rob’s life story through his relationships—with his struggling mother, his incarcerated father, his teachers and friends and fellow drug dealers—The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace comes to encompass the most enduring conflicts in America: race, class, drugs, community, imprisonment, education, family, friendship, and love. Rob’s story is about the collision of two fiercely insular worlds—the ivy-covered campus of Yale University and Newark, New Jersey—and the difficulty of going from one to the other and then back again. It’s about trying to live a decent life in America. But most all, the book is about the life and death of one brilliant man.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

1. The title of The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace reveals its ending. What was it like to read Peace’s life story, knowing how it would end? Was the tragedy present in your mind throughout the reading experience, or were you able to forget it at any point?

2. When Jackie first asked Skeet for tuition to send their son to private school, Skeet called her “uppity” (pp. 22–23). How does the term “uppity” capture the possibilities and pitfalls of Jackie’s aspirations for Rob?

3. Throughout his short life, Rob “strove to project confidence and strength while refusing to show weakness and insecurity” (p. 57). Why do you think Rob refused to ask for help during his many moments of need? What were the direct and indirect consequences of Rob’s projection of confidence?

4. Discuss Rob’s methods of “Newark-proofing”: code-switching to protect himself in the streets of his hometown. According to Rob, how is Newark-proofing compatible with authenticity? How does Newark-proofing compare to “fronting,” a type of role-play that Rob disdained? Do you agree with Rob’s distinction between Newark-proofing and fronting? Why or why not?

5. Consider Rob’s relationship to the drug trade, as both user and seller. How did marijuana affect his intellect, his emotions, and his relationships? Do you think a different legal policy toward marijuana might have affected his life course? Why or why not?

6. Discuss Rob’s attitudes toward money, poverty, and class. In what ways did Rob seek to escape or fix the deprived circumstances of his upbringing? In what ways did he replicate or revert to the cycle of poverty?

7. Consider the complicated journey of Skeet’s conviction, appeals, illness, and death. What were the injustices of Skeet’s experience? How do these injustices mirror larger issues of America’s justice system? How might the crime and its punishment be considered ambiguous or complicated?

8. Jeff Hobbs doesn’t enter the story until almost a third of the way through the book, when he and Rob Peace were matched as college roommates. What was it like to begin this book without “meeting” its narrator? How does the narrative change when Jeff steps onto the page?

9. Discuss the universal and particular elements of Rob’s college experience. What are some of the typical college milestones that Rob experienced at Yale? What was extraordinary or singular about his Yale years? In what ways does Rob’s experience point to larger questions about the value of a college degree today, particularly from an Ivy League school?

10. Consider Oswaldo Gutierrez, Rob’s friend who also traveled from Newark to New Haven and back again. Which of Oswaldo and Rob’s obstacles were similar, and which were different? How does Oswaldo’s current success shed light on Rob’s life choices?

11. Revisit Rob’s “statement of purpose” drafted for graduate school applications, printed in full near the end of the book (pp. 337–40). Why do you think Hobbs chose to print the statement in full—typos and all? What is the effect of reading this rough draft?

12. Jeff Hobbs orchestrates dozens of voices on the life and death of Robert Peace. Of all the perspectives in the book, whose felt most objective? Who, if anyone, might have offered a biased view of Peace’s history?

13. How did you feel when the Burger Boyz were disallowed from attending Rob’s funeral (pp. 392–93)? Could you sympathize with this decision? Do you think these young men deserve forgiveness for any connection with Rob’s death?

14. At Rob’s funeral, in front of four hundred mourners, Raquel compared her friend to a redwood tree, and took “solace in the fact that so many others thrived and found refuge in his shade while he was with us” (p. 390). Why do you think Rob had such a towering influence on so many people? How might that influence extend to the people who “meet” Rob by reading this book?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. Listen to a short interview with Jeff Hobbs on KCRW, the Los Angeles–based radio station: http://blogs.kcrw.com/whichwayla/2014/09/two-unlikely-friends-one-tragic-ending.

2. Watch the Academy Award–nominated PBS documentary Street Fight, about Cory Booker’s 2002 campaign for mayor. Learn more about the film and find websites that stream it here: http://www.streetfightfilm.com/index.html.

3. Mourners have left mix CDs on Rob Peace’s grave site. Using your favorite music-streaming service, compile a mix in tribute to Peace, including some of the songs mentioned in the book: “Southern Hospitality” by Ludacris, “Ride wit Me” by Nelly, “Put It on Me” by Ja Rule, “It Wasn’t Me” by Shaggy, “Forget You” by Cee Lo Green, and “Ruff Ryders’ Anthem” by DMX. Add songs by Tupac Shakur, Biggie Smalls, Nas, and even two of the “prog rock” bands Rob discovered through his friend Hrvoje: the Misfits and Black Flag.

4. Try your hand at Jeff Hobbs’s research methods: choose any friend or loved one as a research subject. Interview three of your subject’s friends or relatives, asking the same two or three questions about the subject’s personal history. Do you get similar versions of the same story, or completely different stories? Discuss your research results with your book club.

A Conversation with Jeff Hobbs

Why did you decide to write this book?

On a Wednesday night in May 2011, while in the midst of brushing my teeth, I learned that my best friend from college had died violently, pointlessly, and painfully. I did what anyone does upon losing someone dear: flew to the funeral, said a few words during the service, bowed my head during the burial, made toasts to Rob having been a “good dude,” mourned, tried to move on. Except that I couldn’t move on; I returned home and found myself spending full workdays staring at the knotty wall planking in the garage where I work, mostly remembering good times had with Rob. I wrote a bunch of personal essays, weaving together college memories with weak attempts at insight, as well as stabbing at the guilt of having allowed our friendship to grow distant over the decade since we’d graduated. I reached out to mutual friends, spent hours talking on the phone and in person, asking each other, of course, why? A community formed around this question, many people from the various spaces of his life connecting with one another. And at some point it became important to people that some record exist—of his life, not only his death.

In the end, there was not so much a specific decisive moment of, “I am going to write a book about Rob,” but rather a process of being caught in this wave of loss and curiosity—of needing to know more—which only gathered strength as weeks and months passed. To some degree, no matter the medium or intention, everyone writes about what conflicts them, and nothing has ever conflicted me more than the death of Rob Peace.

How did Rob’s friends and family react to your intention to write his biography?

To say that Jackie Peace had given all of herself in order to nurture Rob’s intelligence and curiosity in a neighborhood in which neither trait had much currency would be a vast understatement. When she lost him, she lost not only her only child but all those decades of sacrifice—she lost her identity and her hope. I didn’t know Jackie well at all when I first sat down in her living room to speak formally about the book. She told me that her lone consolation after his death was, “I think my son influenced a lot of people, I really do believe that.” Feeling very small in proximity to this woman and her grief, I replied that, if she was willing, I wanted to write a book—a book about Rob’s life, not his death. I told her that there was very little chance of it being published, but I was driven to work to piece his story together, and that if this effort were in fact successful, perhaps he might continue to influence a few people for the better—and might even spare another mother the anguish that she has endured and will endure for the rest of her life. The blessing she gave to this project was courageous and selfless.

As for his friends—and he had an awful lot of friends—reactions were varied. Most were extremely enthusiastic and giving. Some were still too captured by grief to process it. A small few were doubtful of my ability to tell Rob’s story, which was of course a valid doubt.

What were some of the difficulties you faced putting the book together?

Foremost among challenges was the process of exploring a neighborhood foreign to me, and in which my presence was not generally welcome. An inherent discomfort lies in a white guy—a Yale graduate no less—entering the homes of mostly black, mostly struggling people and asking for their stories as they related to a man we both cared for and missed. But that was perhaps the most affecting part of this experience: once we started talking about Rob and exchanging stories filled with humor and warmth, those walls between us tended to come down pretty quickly. Dialogue streamed out of the past and, at times, Rob seemed to spring back into being.

Also challenging was the emotional freight that reporting out this story carried, not only on me personally but on all participants. Positive intention charged all of our efforts, but it was depleting to inhabit such a tragedy day in and day out. I experienced guilt as the details of Rob’s life came out of the dark—guilt that even though I lived with him for four years in a small space and had hundreds of conversations with him, I had never become aware of his whole story. In truth, no one had, not even his mother.

What would you say is the impact of Yale on Rob’s life? If you were advising a teenager in his position, would you recommend Yale?

What Rob said somewhat often was, “I don’t hate Yale, I just hate Yalies.” The entitlement bothered him the most, the blithe energy that coursed through classrooms and parties that we deserved this rare experience more than those who weren’t here. There was this outrage kind of underneath his skin that made him resent his own presence there. That was unhealthy, and if I could go back in time and talk to that version of him, I’d say, “Dude, there are entitled assholes everywhere. They might be more concentrated at Yale for obvious reasons, but wherever you live, wherever you work, there will always be entitlement. The key to living successfully in any environment is to keep from being contaminated by it.” His anger, I think, was a kind of contamination.

I risk painting the picture of this brooding Hamlet figure. Rob was not that. He was a bright light. He became a true scientist there and he made fantastic friendships, lifelong friendships that he took with him. And yes, I think he would advise anyone with the opportunity to go to Yale to go to Yale—to go and take advantage of the plentiful resources available, be they academic or social or emotional resources. Let people in despite your biases against what they may represent. Ask people for help. Yes, it’s a lot to ask of an eighteen- or nineteen-year old experiencing such a drastic and all-encompassing change to have that level of maturity, but listen, college is the last time in your life where you have a stable of people—intelligent people—professors, advisers, upperclassmen—whose job it is to help you. If this book has any influence on college-aged kids, I hope it would be that there is no shame in receiving help, even the simplest kind of help, such as sitting with a friend and permitting them to listen, because never again will help be so close by.

What did you learn about Robert Peace that most surprised you? Troubled you?

You didn’t have to know Rob well to understand that he inhabited two vastly different, fiercely insular worlds: the streets he’d come from and the classrooms his abilities allowed him to enter. That was his broad narrative as reported in the newspaper following his death, that Rob Peace was “two people” (having lived in a small room with him for four years, I can assure you that he was absolutely one person). But what I began to learn even before writing this book was that he didn’t live in two worlds. He lived in ten, fifteen, more. He made communities for himself in Rio and Croatia. He spent much of his life, unbeknown to anyone, working to free his father from prison—writing letters, studying in legal libraries, filing appeals. He mentored hundreds of kids as a high school teacher and coach. He all but carried his friends through the travails of life—academically, emotionally, financially. He lived firmly in the center of all these many spheres, shouldered the dependence of so many people, strived to carry all these various pressures with order and grace—and steadfastly refused help in any form along the way. This dynamic was exacerbated by a pattern that emerged in which none of his friends at Yale felt comfortable or capable of offering advice because of the hard way he’d grown up in Newark, and none of his friends in Newark felt comfortable doing the same because this was the guy who’d graduated from Yale. He was heartbreakingly isolated, even in the midst of his closest friends.

So Rob’s life overall was nothing if not surprising and troubling—all that he achieved, all that he failed to achieve, the manner in which he was killed and all the hundreds of decisions, most of them innocuous in the happening, that brought him to that moment. But even in that context, I encountered so much positivity that I do hope courses through these pages—he faced so many challenges, many self-wrought, many induced by the relentless algorithms of poverty, and he never wilted, he never stopped caring about others and, as his mother told me, influencing others.

Why do you think what happened, happened?

My young daughter, clued in to what I’ve been working on for more than half her life, asked me once: “Why did your friend Rob Peace pass away?” I replied, “He had a lot of bad luck, and he made a lot of bad decisions.” This answer is tailored to a child, but I think it remains the most accurate answer. The fact is, we all experience bad luck, we all make bad decisions. I certainly have. Most of mine have been insignificant. But Rob’s bad decisions—because of the circumstances he was born into and those he wrought for himself—were life-ending.

What was the “meaning of Rob’s life”?

The meaning of Rob’s life is closely linked with the staggering contrasts that life encapsulated. Here is a man who made communities all over the world when he traveled, but couldn’t leave his old neighborhood. A man who aspired to be free of the harried, fiscally based existences that most of us lead, yet ended up bound to one of the most harried, fiscally based occupations there is. A man who performed X-ray crystallography in a cancer research lab but couldn’t own an EZ Pass for fear of being traced by police, and so spent much of his brief life in cash-only toll lines between Newark and Manhattan. A man whose ambition was to teach college chemistry and cook out with his friends and family on weekends, who bled to death in the basement beside a gas mask, a butane tank he used for THC extraction, and the Kevlar vest he wore whenever he went outside.

This is the story of a boy from Orange, New Jersey, who earned his way to Yale, flourished there, and then did what almost everyone in his life told him not to do: he came back. He came back and he taught high school, and he was present for his family, and he traveled, and he loved, and he hustled marijuana, and he stumbled through his twenties the way almost everyone stumbles through their twenties, dwelling on greater purpose and ultimately placing himself within the ever-lurking orbit of ruthless urban violence. That’s a messy story. Because it’s messy being a person, and having a consciousness, and having values, often conflicting values. But it’s also a story about love, and not just the standard associations of grace and depth, but the trickier components, the ones that are hard to confront let alone wrap your head around: the warped logic and impossible loyalties and invisible burdens that love can and does generate.

In a broader cultural sense, what would you hope readers take away from this story?

This is the story of one man’s life, a relatively anonymous man who died because he sold drugs—and that stark fact can be and has been sufficient for any given person to dismiss his story as one of potential wasted in the service of thuggery. And if that’s your reaction, you’re perfectly entitled to it. But this book is about details, it’s about empathy—about remembering that everyone does not experience each moment the same way. It’s about getting to know and understand a remarkable, flawed young man. Yes, his life touches on race and class in this country; yes, it illuminates education and entitlement and access; and yes, it speaks to the fact that living a decent life in America can be tremendously difficult. These issues are quite subjective, and they are best served to remain that way; my intent is not to make statements but simply to tell what happened.

I’ve mentioned the idea of seeking out help. Yale has a comprehensive infrastructure in place, geared primarily toward students whose upbringings haven’t necessarily prepared them for college life—academic, emotional, social. There are guidance counselors and writing tutors and cultural advisers, all free and readily available. But it turns out that the kids most likely to take advantage of these resources are those who need it the least: the Exeter graduates, the future Rhodes Scholars, the affluent students who from the day they were born were primed to believe that adults existed almost exclusively to help them. I’ve cited Rob’s aversion to seeking out help as an admission of not belonging. But what do you do about that gap? Who’s most culpable—the students falling behind or the administration unable to pull them forward?

These are questions that lie under the shadow of broader and more bombastic debates. I don’t know the answers, but I do feel like awareness—and empathy—is where anyone’s potential to do good, maybe even cause change, maybe even save a friend’s life, begins.

Product Details

- Publisher: Scribner (September 23, 2014)

- Length: 416 pages

- ISBN13: 9781476731926

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"Many institutions that provide bridges to realization of The American Dream conflate the aspirant’s yearning to participate fully with a desire to leave everything behind. The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace reveals the devastating consequences of this assumption. There are few road maps for students who carry our much-valued diversity, and few tools for those who remain ignorant of the diverse riches in their midst. Jeff Hobbs has made an important contribution to the literature for all of us. He shows what high quality journalism can aspire to in its own yearning for justice—the urgency of taking a full and accurate account of irreplaceable loss, so we don’t keep making the same mistakes over and over again."

– Adrian Nicole LeBlanc, author of Random Family

“Mesmeric... [Hobbs] asks the consummate American question: Is it possible to reinvent yourself, to sculpture your own destiny?... That one man can contain such contradictions makes for an astonishing,tragic story. In Hobbs’s hands, though, it becomes something more: an interrogation of our national creed of self-invention.... [The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace] deserves a turn in the nation’s pulpit from which it can beg us to see the third world America in our midst.”

– The New York Times Book Review

"A haunting work of nonfiction.... Mr. Hobbs writes in a forthright but not florid way about a heartbreaking story.”

– The New York Times

"I can hardly think of a book that feels more necessary, relevant, and urgent."

– Grantland

"The Short Tragic Life of Robert Peace is a book that is as much about class as it is race. Peace traveled across America’s widening social divide, and Hobbs’ book is an honest, insightful and empathetic account of his sometimes painful, always strange journey."

– The Los Angeles Times

"Devastating. It is a testament to Hobbs’s talents that Peace’s murder still shocks and stings even though we are clued into his fate from the outset....a first-rate book. [Hobbs] has a tremendous ability to empathize with all of his characters without romanticizing any of them."

– Boston Globe

"It is hard to imagine a writer with no personal connection to Peace being able to generate as much emotional traction in this narrative as Hobbs does, to care as much about portraying fully the depth and intricacy of Peace’s life, his friends and the context of it all... it is an enormous writing feat.. fresh, compelling."

– The Washington Post

"[An] intimate biography... Hobbs uses [Peace's] journey as an opportunity to discuss race and class, but he doesn’t let such issues crowd out a sense of his friend’s individuality...By the end, the reader, like the author, desperately wishes that Peace could have had more time."

– The New Yorker

“Heartbreaking.”

– O Magazine

"Captivating... a smart meditation on the false promise of social mobility."

– Bloomsberg BusinessWeek

"Nuanced and shattering.”

– People magazine, "Best Books of Fall"

"The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace is a powerful book meant to haunt us with the question that plagued everyone who knew Peace. Hobbs has the courage not to counterfeit an answer leaving us with the haunting question: Why?"

– The New York Daily News

"The Short and Tragic Life [of Robert Peace] tackles some important topics: the swamp of poverty; the tantalizing hope of education; the question of whether anyone can truly invent a life or whether fate is, in fact, dictated by birth...[Its] account of worlds colliding will leave nagging questions for many readers which might be all to the good."

– The Seattle Times

"A haunting American tragedy for our times."

– Entertainment Weekly

"Can a man transcend the circumstances into which he’s born? Can he embody two wildly divergent souls? To what degree are all of us, more or less, slaves to our environments? Few lives put such questions into starker relief than that of one Robert DeShaun Peace... As Hobbs reveals in tremendously moving and painstaking detail, [Peace] may have never had a chance."

– San Francisco Chronicle

"Mr. Hobbs chronicles Peace’s brief 30 years on earth with descriptive detail and penetrating prose...

He paints a picture of a young man who was complex, like most of us, and depicted both his faults and admirable qualities equally. It is up to the reader to decide if Peace was an Ivy League grad caught up in a life of crime or just a victim of circumstances... Mr. Hobbs’ empathetic narrative gives readers an opportunity to view his life beyond a stereotype."

– Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

"With novelistic detail and deep insight, Hobbs... registers the disadvantages his friend faced while avoiding hackneyed fatalism and sociology... reveals a man whose singular experience and charisma made him simultaneously an outsider and a leader in both New Hampshire and Newark... This is a classic tragedy of a man who, with the best intentions, chooses an ineluctable path to disaster."

– Publishers Weekly, STARRED review

"Ambitious, moving...Hobbs combines memoir, sociological analysis and urban narrative elements, producing a perceptive page-turner... An urgent report on the state of American aspirations and a haunting dispatch from forsaken streets."

– Kirkus, STARRED review

"Peace navigated the clashing cultures of urban poverty and Ivy League privilege, never quite finding a place where his particular brand of nerdiness and cool could coexist... [Hobbs] set out to offer a full picture of a very complicated individual. Writing with the intimacy of a close friend, Hobbs slowly reveals Peace as far more than a cliché of amazing potential squandered."

– Booklist, STARRED review

"One part biography and one part study of poverty in the United States, Hobbs's account of his friend's life and death highlights how our pasts shape us, and how our eternal search for a place of safety and belonging can prove to be dangerous. Peace's life was indeed short and tragic, but Hobbs aims to guarantee that it will not go unmarked."

– Shelf Awareness, STARRED review

"The resulting portrait of Peace is nuance, contradictory, elusive, and probing... At its core, the story compels readers to question how much one can really know about another person... VERDICT: An intelligent, provocative book, recommended for any biography lover."

– Library Journal

“If The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace were a novel, it would be a moral fable for our times; as nonfiction, it is one of the saddest and most devastating books I’ve ever read, a tour-de-force of compassion and insight, an exquisite elegy for a person, for a time of life, for a valid hope that nonetheless failed. It is also a profound reflection on a society that professes to value social mobility, but that often does not or cannot imbue privilege with justice. It is written with clarity, precision, and tenderness, without judgment, with immense kindness, and with a quiet poetry. Few books transform us, but this one has changed me forever.”

– Andrew Solomon, author of Far From the Tree and Noonday Demon

“Jeff Hobbs has written a mesmerizingly beautiful book, a mournful, yet joyous celebration of his friend Robert Peace, this full-throated, loving, complicated man whose journey feels simultaneously heroic and tragic. This book is an absolute triumph—of empathy and of storytelling. Hobbs has accomplished something extraordinary: he’s made me feel like Peace was a part of my life, as well. Trust me on this, Peace is someone you need to get to know. He’ll leave you smiling. His story will leave you shaken.”

– Alex Kotlowitz, author of There Are No Children Here: The Story of Two Boys Growing Up in the Other America

“A poignant and powerful can’t-put-it-down book about friendship and loss. The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace takes you on a nail-biting, heartbreaking journey that will leave you moved, shaken, and ultimately changed. In this spectacularly written first work of non-fiction, Jeff Hobbs creates a singular and searing portrait of an unforgettable life.”

– Jennifer Gonnerman, author of Life on the Outside: The Prison Odyssey of Elaine Bartlett

Awards and Honors

- Carnegie Medal Honor Book

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace eBook 9781476731926

- Author Photo (jpg): Jeff Hobbs Photograph by Lucy Hobbs(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit